Since I came of age, I have struggled to clearly grasp what Ghana’s long-term developmental vision truly is. We’ve produced brilliant blueprints like Vision 2057 – a comprehensive roadmap envisioning a free, just, prosperous and self-reliant Ghana by our centenary in 2057.

It’s a thoughtful, inclusive and well-crafted plan that integrates economic, social, and environmental goals. Yet it sits largely ignored by successive governments, shelved in favour of campaign-driven manifestos.

And so, like a ship without a compass, we drift – committing to ambitious visions only to abandon them midway. Meanwhile, other countries push forward with determination and clarity.

I had always imagined Egypt as a country of ancient wonders and glorious relics. I never saw it as a model of modern development in Africa. But my three-week training in Cairo alongside 24 young African journalists from 14 countries changed that perception forever.

We toured Alexandria’s storied coastlines, wandered the narrow, sacred alleys of Old Cairo, and basked in the energy of New Cairo’s lively markets. But what struck me the most was Egypt’s New Administrative Capital – a bold, deliberate and sweeping declaration of a country that knows exactly what it wants.

The city is 35 kilometres east of Cairo, sprawling across 170,000 feddans – an ambitious, multi-phase megaproject that will soon house over 8 million people. It’s already 70 percent complete. Designed with sustainability, technology, and governance in mind, it embodies Egypt’s intention to decentralise its population, digitise public services, and attract global investment – all without draining state resources. The $40 billion project, creating about 2 million jobs, is funded by the Administrative Capital for Urban Development Company, not the government.

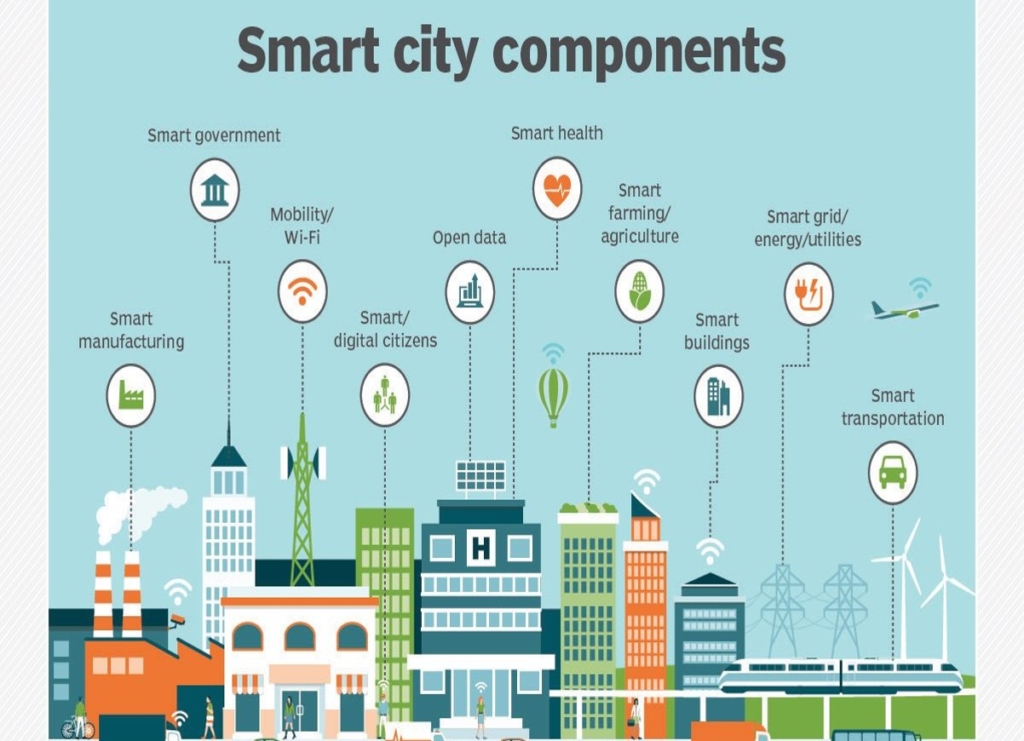

Everything about this new capital is intentional. The infrastructure is smart and sustainable, drawing 30 percent of its energy from solar panels. Government ministries sit side by side in a layout that fuses Islamic, Pharaonic, and modern architectural styles.

Transactions are paperless. Services are integrated. The city’s core houses not only the Cabinet, Parliament and Senate but also top banks and tech hubs. This is not a city built for show. It’s a functional, future-ready space designed to serve.

But Egypt’s ambition does not stop there. Across the Mediterranean coast, a new tech-tourism hub is emerging in New Alamein, while in the arid desert, New Toshki is transforming barren land into an agricultural powerhouse. The drive to create “fourth-generation” cities – smart, decentralised and sustainable – is no accident. It is a blueprint, one that fuses urban planning, technology and economic vision into a coherent national strategy.

Beyond physical infrastructure, Egypt’s strides in public health are equally remarkable. In 2020, the World Health Organisation certified Egypt malaria-free – a triumph achieved through relentless surveillance, aggressive vector control and deep community engagement. Egypt is now extending this success continent-wide through its “Malaria-Free Africa” programme, training health workers in high-burden countries.

Perhaps even more stunning is Egypt’s near-eradication of Hepatitis C. Through the “100 Million Seha” campaign, the country screened over 60 million people and treated 4 million, slashing national prevalence from 15 per cent to less than 1 per cent. Today, Egypt is sharing its expertise with South Sudan, Chad and Eritrea, treating 1 million Africans and showing that health victories can indeed cross borders.

As I listened to the Vice President of the ACUD share Egypt’s journey and as we engaged officials at the North Africa Regional Office, I couldn’t help but reflect again on Ghana – and the cost of political short-sightedness.

Why do countries like Egypt, China, Malaysia and even Dubai surge ahead? Because they remain stubbornly committed to long-term national visions, regardless of changes in leadership. China, for instance, stuck to reforms started in the 1980s. Malaysia, our independence twin, has stayed consistent with infrastructure growth, industrial policy and economic transformation. Dubai – once soliciting African support – has, within a generation, morphed into a global powerhouse.

Egypt teaches that infrastructure alone does not drive transformation. Parallel investments in transportation like the $8.7 billion high-speed rail network by Siemens and the digital economy through universal broadband access and the “Digital Egypt” e-governance platform deliberately broaden opportunity and access.

Social programmes are central too. The “Decent Life” initiative delivers direct cash transfers to the elderly and vulnerable (Ghana’s version of the Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP) Initiative), while building over a million units of social housing. Women’s empowerment efforts target a 35 per cent workforce participation rate, supported by microfinance schemes and anti-discrimination legislation.

Even as Egypt modernises, it refuses to abandon its cultural soul. Investments in heritage restoration like the Grand Egyptian Museum and the revitalisation of Luxor’s historic sites ensure that development does not erase identity but amplifies it. Egypt’s booming tourism sector, spanning Red Sea eco-tourism to luxury resorts at Alamein, now stands as a vital economic pillar.

On the continental stage, Egypt is stepping up too – training health workers, sharing lab infrastructure, transferring smart-farming technology, and collaborating on water security along the Nile.

What does Ghana want? And crucially, what are we prepared to commit to in order to get there?

My visit to Egypt gave me no illusions that development is easy. But it affirmed that it is possible if there is clarity of purpose and discipline of execution. Egypt’s new capital, its public health victories, its smart cities, its heritage investments – none are perfect, none without challenges. But together, they stand as monuments of ambition backed by action.

Beyond the infrastructure, I was deeply moved by Egypt’s embrace of its rich, layered cultural identity – from the Hanging Church and Amr Ibn al-As Mosque in Old Cairo to the seamless coexistence of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. I saw people proud of their past yet determined to shape the future. I saw a government willing to think beyond six-year political cycles.

As an African journalist, I was there to learn. But I left Egypt with something deeper: a renewed belief in what’s possible when a country truly knows what it wants and goes for it.

I hope Ghana gets there soon.

Emmanuel Dzivenu is a broadcast journalist with The Multimedia Group Limited, specialising in human interest journalism, with a strong focus on disability, education, health and climate reporting. His work spans television, radio, and digital platforms, producing in-depth documentaries, special reports, and feature stories that spotlight underreported communities and national issues.

Emmanuel is also an experienced producer and showrunner, having led high-impact youth dialogues, street debates, and multi-platform campaigns that shape public discourse. His storytelling is grounded in rigorous research, community engagement, and visual depth, making his work both relatable and policy-relevant.

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.