Fubara’s Shocking Rebuke: “Do You Even Know If I Want To Go Back There?”

The Boy Who Broke in Public: He Did Not Fight His Supporters

Before the cameras, Fubara did not roar. He trembled. His voice cracked—not with rebellion, but with weariness. And through that simple question—“Do you even know if I want to go back there?”—he revealed a truth few in power ever dare to admit: he was not sure he wanted to continue.

The misreading of that moment is telling. Some thought he had turned on his base. Some said he no longer wished to lead. But those closest to the psychology of African politics knew better. Fubara was not rejecting his supporters. He was mourning the weight of being owned.

Fubara has not fought the people. He has been too busy fighting the system. The rituals of hierarchy. The expectations of the godfather. The silent rules written long before he ever stepped into office. In that moment of visible despair, we were not witnessing defiance—we were witnessing collapse.

He was never groomed to lead. He was placed to obey. But somewhere along the line, he tried to think. And for that, the system began to crush him.

Supporters must not mistake his exhaustion for betrayal. What they are seeing is not absence—it is suffocation. Not indifference—but deep spiritual confusion. Fubara is not standing against the people. He is standing alone in front of a machine that rewards silence and punishes growth.

That is why his voice did not rise—it cracked. Because African politics does not often allow boys to become men. It prefers they remain boys forever.

And for once, in that brief moment of vulnerability, one of those “boys” told the truth.

He whispered: “Do you even know if I want to go back there?”

What we saw was a man under siege—not just politically, but spiritually. His voice, trembling with disillusionment, came not from rebellion but from fatigue. He was not launching a counterattack—he was whispering a cry for air.

Fubara’s spirit had already vacated the seat long before any court or presidency officially removed him. This reveals a tragic truth in many African nations: leaders are often chosen not for their vision, but for their loyalty. Not for their independence, but for their obedience.

Many are selected for high office precisely because they pose no threat to the godfathers who placed them there. And once they show even the faintest sign of independent thought, the system punishes them—not politically, but emotionally and institutionally.

Fubara’s disillusionment reveals the psychological violence of being a placeholder. He has become the symbol of a deeper African tragedy—leaders who are paraded as governors but governed from behind curtains.

His words—“Do you even know if I want to go back there?”—cut deeper than politics. They expose the emptiness of power when stripped of freedom. The burden of the crown becomes unbearable when it is not worn, but forced.

What we saw was a man under siege—not just politically, but spiritually. His voice, trembling with disillusionment, came not from rebellion but from fatigue. He was not launching a counterattack—he was whispering a cry for air.

Fubara’s spirit had already vacated the seat long before any court or presidency officially removed him. This reveals a tragic truth in many African nations: leaders are often chosen not for their vision, but for their loyalty. Not for their independence, but for their obedience.

Many are selected for high office precisely because they pose no threat to the godfathers who placed them there. And once they show even the faintest sign of independent thought, the system punishes them—not politically, but emotionally and institutionally.

Fubara’s disillusionment reveals the psychological violence of being a placeholder. He has become the symbol of a deeper African tragedy—leaders who are paraded as governors but governed from behind curtains.

His words—“Do you even know if I want to go back there?”—cut deeper than politics. They expose the emptiness of power when stripped of freedom. The burden of the crown becomes unbearable when it is not worn, but forced.

The Child Who Refuses to Fight the Father

Fubara was never supposed to fight. He was not trained for war. He was handed the sword with no map. A soft-spoken accountant suddenly found himself in a theater of ancient political combat. He did not rise by rallying the people—he was lifted, named, positioned by Wike.

In African political psychology, this makes him a “son.” A crowned servant. A man who owes, not a man who owns.

But something changed. Fubara tasted independence. He began to breathe beyond the mask he was given. And in a system like Nigeria’s, that cannot be tolerated.

He had to be reminded: you are not here to think. You are here to serve.

This is the African tragedy of imposed leadership: when a man is selected to rule without the freedom to lead, he becomes a hostage in a robe of power.

Fubara is now that hostage. His tears, his silence, his pauses—they are all evidence of a man grappling with betrayal, pressure, and the unbearable cost of thought.

Wike’s Narrative: “They Are Pushing My Boy to Fight Me”

And then Wike spoke—not with anger, but with claim:

“He is my son. They are pushing my boy to fight me.”

This is no longer politics—it is theatre. And in African theatre, the godfather plays the eternal wise man, and the son must remain confused. Wike’s words are not a show of concern—they are narrative weapons. By framing Fubara as manipulated, Wike removes his agency and portrays himself as the victim of third-party betrayal.

This is classic power retention—reclaim moral superiority by infantilizing your challenger. The father becomes the betrayed. The son, the corrupted.

It is emotional control disguised as compassion. A psychological chess move that recasts rebellion as immaturity.

The Patriarch’s Intervention: Tinubu as the Ultimate Father Figure

And then entered Tinubu—the president, the final father.

When Tinubu told Wike to “settle with Fubara,” it was not institutional. It was ancestral. This was not a constitutional intervention—it was elders meeting in a spiritual hut, cloaked in modern suits.

The court was not consulted. The legislature was irrelevant. Instead, Fubara traveled to London—not for policy, but for penance.

This is Africa’s deeper crisis: when governance is handled not in public chambers, but in whispered conversations among powerful men.

And thus, Nigeria became a stage where elders settle disputes, and the masses merely watch. Institutions shrink. Symbolism expands. And the people are left in the shadows of a feud they neither caused nor can resolve.

The Wounded Child: Calls, Visits, and the Performance of Uncertainty

Then came the visits, the calls, the greetings. Wike revealed:

“He called me. I called him. He visited me. He tear up?”

These are not gestures of peace. They are rites of control. In many African traditions, when the son bows before the elder, it is not for reconciliation—it is a ritual of repentance.

This is not politics. This is a spiritual contract.

Fubara’s bowing, calling, and silence are seen as proof that the child has returned. That the rebellion is over. That the father remains supreme.

But behind the bows lies a broken man. Behind the camera smiles is a man whose public appearance masks a private prison.

In Africa, survival often requires public performance. Fubara’scompliance is not peace—it is strategic suffering.

Final Reflection: The Man Who Dared to Shine

Fubara did not betray the people. He blinked.

His hesitation, silence, and emotional restraint are not signs of cowardice. They are the reflections of a man overwhelmed by the burden of a political seat he was never fully empowered to own. He is not confused—he is cautious. Not weak—but wounded.

In a healthier democracy, his thoughtful nature and preference for peace might be praised. But in a system dominated by godfathers and ancestral control, his calmness is misread as disloyalty, and his silence mistaken for guilt.

He may return to office, but not in freedom. He may wear the crown again, but not without conditions. He will return with boundaries—taught what to say, who to trust, and when to bow. That is not leadership. That is political survival.

Until African politics replaces personality worship with democratic principles, and until Nigeria chooses institutions over individuals, we will continue to witness this cycle: leaders who rule not from the people’s mandate but from inherited instructions.

But there is still hope. No empire of ego survives forever. One day, power will be earned, not handed down. One day, institutions—not men—will hold the highest authority. One day, a Nigerian governor will speak and act freely, with loyalty only to the people and the law.

And may that day not remain a distant idea, but begin in the living, breathing, democratic life of Nigeria.

When that day comes, we will remember the man who whispered:

“Do you even know if I want to go back there?”

And we will answer:

You shouldn’t have had to ask. if I want to go back there?”

And we will answer:

You shouldn’t have had to ask.

Fubara did not betray the people. He blinked.

His pain, hesitation, and seeming ambiguity are not signs of cowardice. They are symptoms of a man drowning in the contradictions of inherited office and suppressed autonomy. In a different system, his temperament might have been an asset. But in the suffocating climate of African strongman politics, doubt is seen as weakness, and patience as rebellion.

He will likely return to his seat, but not as a free man. He will return bound—an institutional leader, but a personal subordinate. He will return with lessons etched into his will: never outgrow your godfather, never forget who fed you, never dream too freely.

And until African societies replace loyalty to men with loyalty to principles—until constitutions replace cults of personality—we will continue to produce leaders who rule in chains.

Still, there is hope. Because history shows that no empire of ego lasts forever. One day, institutional power—not personal power—will rise. One day, law will overrule lineage. One day, governance will no longer be a family affair.

And may that day begin—not in theory, but in the lived reality of Nigeria.

Fubara did not abandon his people. He abandoned confrontation. He is walking on fire, trying to save dignity without inviting doom.

He was pulled from accounting books into power. He was crowned, not chosen. And now he is punished for showing signs of a mind.

Yes—he will likely return. But as what?

Not as a free leader. Not as a man of the people.

He will return with spiritual handcuffs. With coded rules. With new obedience rituals.

He will be told who to talk to. What to say. Who to align with. What not to think.

This is not leadership. It is managed servanthood.

And until African societies break this circle—until we allow our sons to grow into men, and our institutions to overrule our elders—we will remain governed not by laws, but by lineage.

This is not just Fubara’s crisis. It is Africa’s generational curse.

And yet, even in this darkness, there remains a flicker of hope: one day, institutional power—not personal power—will rise in Africa. And when it does, it will no longer matter who calls whom “my boy,” because the rule of law, not the rule of men, will lead. Nigeria especially must be the place where this new dawn begins.

When that day comes, we will remember the man who whispered:

“Do you even know if I want to go back there?”

And we will answer:

You shouldn’t have had to ask.

This writer does not know any of the individuals involved; the focus is solely on upholding democracy, truth, and justice.

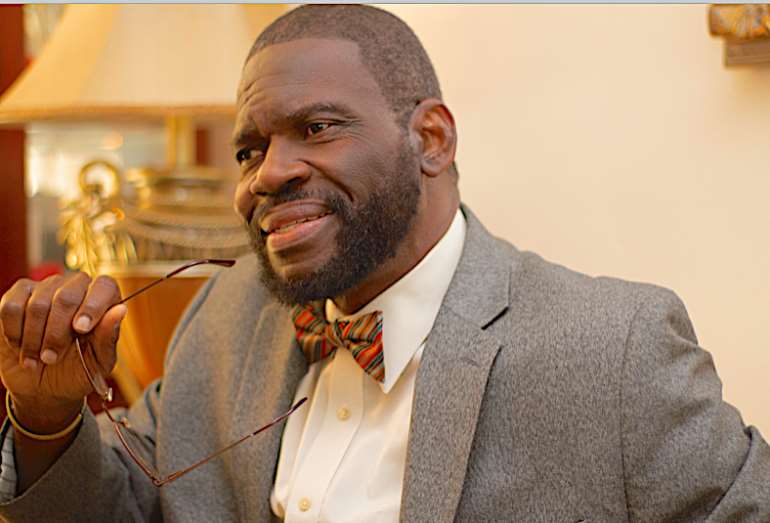

Psychologist John Egbeazien Oshodi

Professor John Egbeazien Oshodi is an American psychologist, educator, and author specializing in forensic, legal, and clinical psychology, cross-cultural psychology, police and prison sciences, and community justice. Born in Uromi, Edo State, Nigeria, he is the son of a 37-year veteran of the Nigeria Police Force—an experience that shaped his enduring commitment to justice, security, and psychological reform.

A pioneer in the field, he introduced state-of-the-art forensic psychology to Nigeria in 2011 through the National Universities Commission and Nasarawa State University, where he served as Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology. His contributions extend beyond academia through the Oshodi Foundation and the Center for Psychological and Forensic Services, advancing mental health, behavioral reform, and institutional transformation.

Professor Oshodi has held faculty positions at Florida Memorial University, Florida International University, Broward College, where he also served as Assistant Professor and Interim Associate Dean, Nova Southeastern University, and Lynn University. He is currently a contributing faculty member at Walden University and a virtual professor with WeldiosUniversity and ISCOM University.

In the United States, he serves as a government consultant in forensic-clinical psychology, offering expertise in mental health, behavioral analysis, and institutional evaluation. He is also the founder of Psychoafricalysis, a theoretical framework that integrates African sociocultural dynamics into modern psychology.

A proud Black Republican, Professor Oshodi advocates for individual empowerment, ethical leadership, and institutional integrity. His work focuses on promoting functional governance and sustainable development across Africa.