In recent years, a rather troubling narrative has continued to gain traction across Nigeria and parts of West Africa. The palpable fear was that the Fulani ethnic groups who are basically pastoralists and are dispersed across the continent, had determined to overrun and dominate, or even Islamize entire Nigerian regions. Unfortunately, many Nigerians were oblivious of the fact that this narrative had only been amplified by political tension, ethnic clashes, and escalating insecurity in parts of the country. But, even at that, how reliable was the narrative, to have resulted in the massive fear that subsequently gripped the citizens of, especially, the eastern states?

The truth, when examined through historical and geopolitical lenses, tells a different story, a story that reveals more about modern political trends and fear-mongering than it does about Fulani intentions or capabilities. It has been established, for instance, that the Fulani are spread across about fifteen African countries which include Cameroon, Chad, Guinea, Mali, Nigeria and Senegal. The history of the Fulani is also distinguished by constant migration, cattle herding, and Islamic scholarship. They are one of Africa’s largest and most widely dispersed ethnic groups, known more for their mobility and adaptability than for the conquest of anywhere on the continent.

Between 1804 and 1830, for example, some Fulani clerics and leaders had led Islamic jihadists to topple corrupt or pagan regimes within the sub-Saharan African region. Among the most notable was Usman dan Fodio’s Sokoto Caliphate, established in 1804. The territory spanned today’s Sokoto, Kano, Kaduna, Katsina, Bauchi, Gombe, Adamawa, Ilorin, Niger, and parts of Niger and Cameroon Republics. But even this so-called conquest was only religious and reformist in nature. It was not an ethnic occupation in any sense. On the contrary, the caliphate was ethnically inclusive. Hausa, Kanuri, and other peoples were integrated into the ruling structure based on Islamic ideals, not on Fulani identity. Similar Islamic states emerged in Guinea, Senegal, Mauritania and Mali, all of them led by Fulani elites but driven more by Islamic reform than Fulani nationalism. That none of these efforts led to the overrunning of any country in the modern sense is also important.

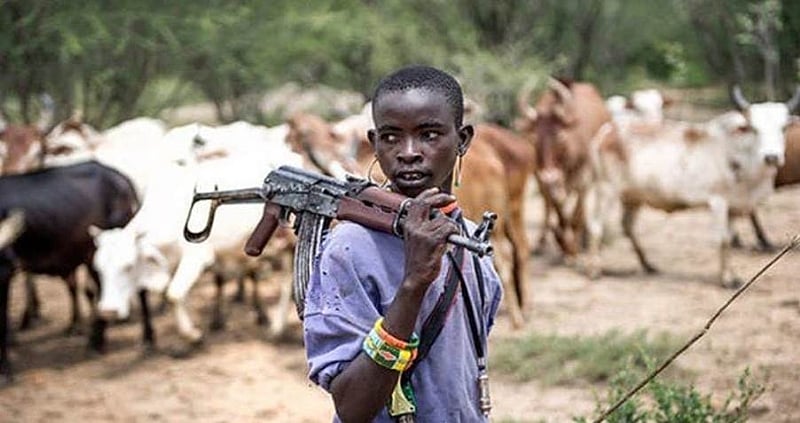

In modern-day Nigeria, the Fulani herder-farmer conflict metamorphosed more or less into a national security nightmare. Thousands of lives were lost in states like Benue, Plateau, Kaduna, Taraba, and other regions. For whatever reason, the conflicts were often framed with ethnic or religious bias, leading many to believe that the Fulani were attempting a covert takeover of some Nigerian states or even regions. Yet, a deeper analysis shows that violence was often triggered mainly by competition over land and water resources and that the situation was worsened by climate change, population pressure, and the breakdown of traditional conflict-resolution mechanisms. With Nigeria’s northern states becoming increasingly arid, herders had to migrate southward and most times they clashed with settled farming communities.

President Tinubu and elders of Igboland

Unscrupulous Nigerian political actors did not hesitate to exploit such crises, using them to stoke ethnic and religious sentiments, especially during election seasons. The resulting narrative would often paint the Fulani in an imposing, villainous stance. And of-course, that was both unfair and dangerous. There is simply no way the Fulani can overrun and occupy any part of Nigeria and there are many reasons why they just cannot do that. One major reason is that the Nigerian federation is made up of over 250 ethnic groups, each with its own social structures, cultural pride, and history of resistance. The idea that one ethnic group, no matter how widespread, could successfully dominate or occupy any other region by force is logistically and politically unrealistic, and therefore, unrealisable.

Contrary to popular belief, there is no single Fulani agenda anywhere in Africa. For instance, the Fulani of Adamawa are different from those in Katsina or Niger, and many have intermarried with other groups. There is no central Fulani authority that is controlling herders or orchestrating violence, not even Miyetti Allah that many think is sponsoring the herders. In many ways, Miyetti Allah is just a trade union like many southern states have their towns’ unions looking after their welfare. While some criminal elements among herders carry arms, they are not structured or funded in a way that could enable military-style occupations of any part of a Nigerian state. Banditry, not invasion or occupation, is the accurate word for their violence. The important fact, however, is that organized crime only thrives in the absence of state control, not as a tool for ethnic conquest. In places like Mali and Burkina Faso, Fulani civilians had been massacred by both jihadist groups and anti-Fulani militias. In Nigeria, innocent Fulani families had also been killed in revenge attacks. So, their identity as always the aggressors is more often a matter of projection, and not the real truth.

Modern Cattle Ranching

The belief among many southeastern Nigerians that the Fulani have a secret agenda to overrun and occupy their region grew largely from unwarranted fear emanating from lived experience of violence, political rhetoric, and a deep historical mistrust that was rooted in Nigeria’s complex ethnic dynamics. Over the last two decades, the South East and nearby South-South have witnessed several violent confrontations between Fulani herders and local farming communities. These resulted in the destruction of farmlands by roaming cattle. There were monumental reports of kidnappings, rape and killings, attributed to armed herders. In several instances, these Fulani established camps in remote forests and along highways that were perceived as threats by local communities.

The inability or unwillingness of federal authorities, often perceived as pro-Fulani, to hold any of the perpetrators accountable also fanned the embers of suspicion and distrust among the south easterners. To many people, unfortunately, these acts did not suggest criminality. They saw them as an attempt at “invasion.” Many south easterners believed that the federal government, which had often been led by northern Fulani politicians like the former President, Muhammadu Buhari, showed much indifference or even complicity when Fulani groups were accused of violence. With no motivations on the part of the government to arrest and prosecute identified culprits, it was widely believed that the federal government was bent on protecting Fulani interests and that Fulani herders were being used as tool for the broader land grab or Islamization plans.

Such proposals as the now-suspended “Ruga” settlements and “National Grazing Routes” were interpreted by easterners as attempts to legally settle Fulani herders in the southern states, effectively placing non-indigenous people on ancestral lands. In the Southeast, this triggered fierce resistance based on suspicion of colonization through policy. The Igbo people, who form the bulk of southeastern Nigeria, still bear the scars of the 1967–1970 Nigerian civil war. Their traumatic history of marginalization, war, and loss makes many of the Igbo wary of perceived threats to autonomy and possession of their land. But in reality, the idea that the Fulani, whether they are herders, militants, or politicians, could successfully overrun and occupy the Southeast is extremely unlikely for many reasons.

For one, the Fulani are not a single political or military bloc. They are ethnically linked but socially and politically diverse, with internal differences in language, in lifestyles of the nomadic and the settled, in religion where some are Christians, and in their loyalty. There is no evidence of a centralized Fulani command plotting territorial conquest of anywhere on the African continent. Besides, the Southeast is densely populated, their people culturally cohesive and fiercely protective of their lands and heritage. Any external attempt to “occupy” the region would decidedly face formidable resistance. The land itself is well-known by the owners because communities are tight-knit and so, any Fulani attempt at encroachment would be quickly noticed and resisted.

That notwithstanding, the Nigerian military and security agencies are still powerful enough to prevent large-scale territorial occupation by non-state actors. Moreover, local vigilante groups like the Eastern Security Network (ESN) have emerged specifically to counter such threats, though they came with their own controversies. In addition to all these, Nigeria is known to be under constant domestic and international observation. Any ethnic-based attempt to conquer a region would spark a national crisis, global outrage, and the likely intervention of international organizations and human rights groups.

It is also important that when the Fulani, historically, led Islamic jihadists to topple kingdoms in West Africa between 1804 and1830, they did not do so for ethnic expansion, but to reform Islam. Even those movements were limited to the Sahel and Savannah zones of West Africa. No Fulani-led force has ever attempted to overrun or “occupy” the southern rainforests, especially in the contemporary era. While the fears of the southeastern people are not entirely irrational, given real incidents of violence and political ambiguity, the belief in a secret Fulani agenda to occupy the Southeast is not supported by logistical, historical, or political facts and therefore it cannot work.

As things stand at the moment, what Nigerians urgently need is transparent and inclusive security policies and justice for victims of herder-farmer violence, regardless of ethnicity. They also need a national dialogue that would de-escalate ethnic suspicion and escalate community-level cooperation and conflict resolution mechanisms. Ultimately, fears lose relevance when government is accountable and justice is visibly applied. Instead of amplifying fear and division, national leaders and media voices should advocate for strengthening local governance and security in rural communities. Nigeria should be investing in ranching systems to modernize livestock management, implement civic education campaigns to reduce ethnic stereotyping and institute accountability for criminal acts, irrespective of ethnicity.

It is obvious that the fear of Fulani domination of any part of Nigeria is not rooted in historical or contemporary reality. It is, at best, a distortion of history and, at worst, a tool for political manipulation. While Fulani-related violence is a real and tragic problem in countries like Nigeria, solving it requires policy innovation, not ethnic scapegoating. In the complex, multi-ethnic reality of African nations, especially Nigeria, no single group can “overrun” others without massive and sustained support from state actors or foreign powers. The Fulani are neither organized nor motivated for such a mission. They, like many others, are simply navigating the chaos that is modern African survival instinct. So, Nigerians should begin to see the Fulani question not as a tribal conspiracy but as a governance failure. What is needed is not suspicion but reform of land-use laws, security services, and traditional grazing systems. The Fulani have never overrun or occupied any country in Africa. And they will not start now. So, it is time to reject those unwarranted fears and embrace the truth of the matter on the ground.