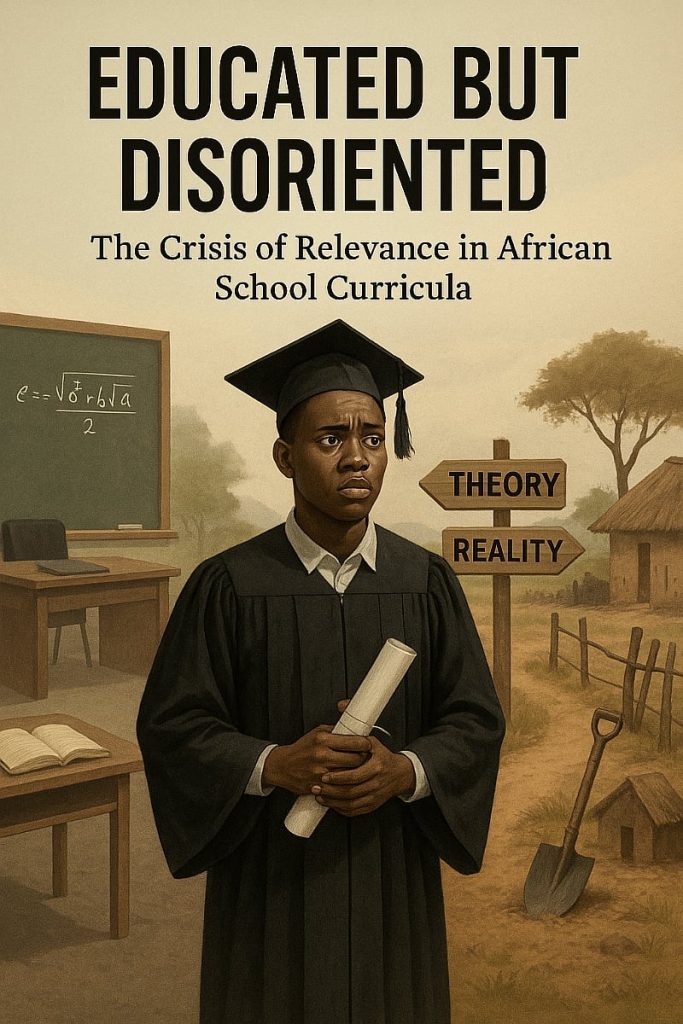

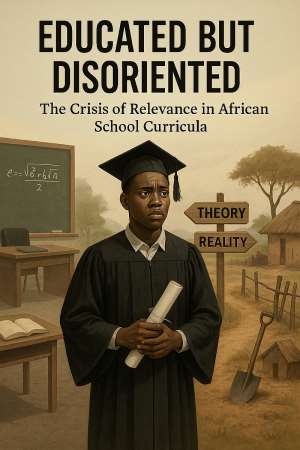

In many African nations, education is hailed as the golden key to success both personal and national. Classrooms are filled with eager learners, textbooks borrowed from foreign systems, and curricula that still echo the colonial past. Yet, the streets are flooded with graduates who are not only unemployed but disoriented, disconnected from their environment, alienated from their communities, and struggling to find meaning in the very education they were promised would liberate them.

This is the crisis we must confront: Africa’s school systems are producing “educated” individuals who remain structurally disempowered, culturally detached, and economically sidelined. There is a glaring disconnect between what is taught and what is truly needed.

Colonial Echoes in Postcolonial Classrooms

The roots of this crisis can be traced to colonial educational models designed not to empower Africans, but to produce clerks, interpreters, and administrators loyal to the colonial enterprise. Decades after independence, these outdated systems remain largely unchanged. While the rest of the world moves toward contextualized, skill-based learning, African students are still asked to memorize British poems or solve abstract math problems that have little real-life application.

Students are taught to define feudalism in Europe, yet many leave school without ever learning about Ubuntu, Sankofa, or precolonial African governance systems. The result is an education that detaches learners from their cultural roots while offering minimal relevance to the economic and social realities around them.

Certificates Without Competence

A tragic irony of Africa’s education landscape is how a system meant to defeat ignorance ends up producing graduates with little competence outside the exam hall. Many school leavers cannot start a business, manage basic finances, farm effectively, or engage in meaningful civic dialogue. Their knowledge is often limited to passing standardized exams not solving real-world problems.

Ask a graduate of agricultural science how to rear poultry or preserve fish sustainably, and you may be met with silence. Ask an economics student about managing a village cooperative, and they may respond with macroeconomic jargon that holds no practical value. This is not just a gap, it is a gaping wound.

The Trap of Unemployability

Each year, universities and secondary schools churn out hundreds of thousands of graduates, yet the job market barely reacts. Employers lament that graduates are not “job-ready.” Youth, in turn, feel betrayed by an education system that promised prosperity but delivered little more than a laminated certificate.

This frustration has fueled the rise of “magic centers” illegal exam coaching outfits that leak WAEC and JAMB questions in advance. These centers are merely symptoms of a deeper disease: when education loses its relevance, cheating becomes a shortcut to hollow credentials.

Reclaiming Relevance: A New Vision for African Curricula

African governments, educators, and stakeholders must urgently redefine the purpose of education on the continent. The central question must be: What kind of citizen are we trying to produce?

Here’s a roadmap to reform:

1. Contextualize Content: Curricula must reflect African history, geography, economics, languages, and lived realities. Let students read Achebe and Ngũgĩ alongside Shakespeare and Dickens.

2. Prioritize Skills Over Scores: Embed vocational training, digital literacy, and entrepreneurship into all levels of learning. Certificates should signify capacity, not just compliance.

3. Promote Mother Tongue Education: Languages shape worldview. Early education should begin in local languages, gradually integrating national and international ones.

4. Reconnect Education to Community: Encourage projects and research that address local challenges in agriculture, sanitation, governance, and climate change.

5. Retrain the Teachers: Reforming the curriculum without empowering teachers is futile. Teachers must be equipped to facilitate transformative learning, not just deliver outdated content.

Conclusion: Toward an Education That Transforms

Kwame Nkrumah once declared: “Seek ye first the political kingdom and all things shall be added unto you.” Today, the call might be: “Seek ye first an education that is relevant and all development shall follow.”

Africa stands at a critical crossroads. We must choose between perpetuating an inherited system that no longer serves us, or boldly building one that aligns with our realities and aspirations. This is the only path toward raising a generation that is not just educated but empowered.

Education must not only inform. It must transform.