🔍 Introduction

History is not simply the story of what happened—it is the memory of how power was used, values encoded, and institutions formed to channel both vision and restraint. Long before the language of constitutions and reform echoed through parliaments and courts, early civilizations were already experimenting with authority, justice, and moral leadership.

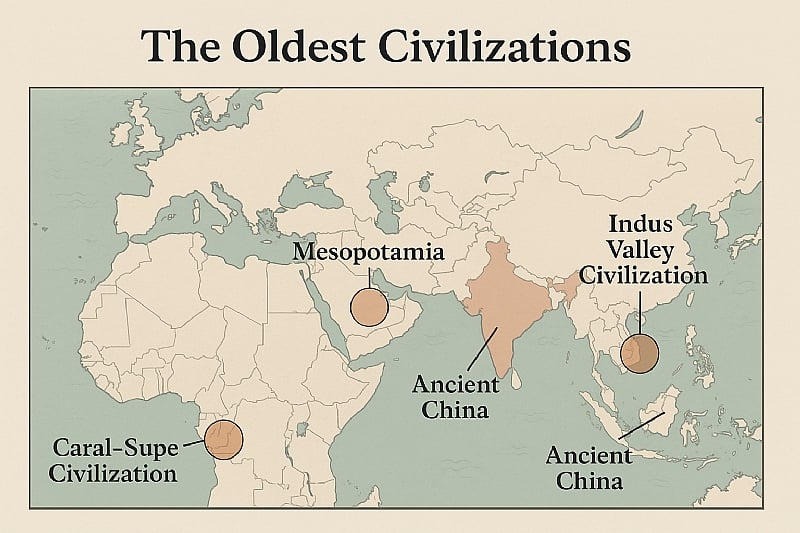

This paper follows the footprints of the world’s earliest societies—not merely to admire their monuments, but to unearth the principles they embedded into governance, ethics, and citizenship. In understanding how the Sumerians, Egyptians, Indus Valley dwellers, Zhou philosophers, and Andean architects governed, we catch a mirror glimpse of our modern aspirations—and our enduring struggles.

🪔 Mesopotamia: Where Power First Met Law

Among the reeds and riverbanks of Mesopotamia, the Sumerians gave the world cuneiform—a tool not only for trade, but for governance. In city-states like Uruk and Lagash, early rulers grappled with the demands of justice, inequality, and sacred duty.

✨ Urukagina of Lagash, a reform-minded king circa 24th century BCE, issued edicts that curbed elite exploitation and protected widows and orphans. His governance wasn’t just procedural—it was moral.

🗿 Then came Hammurabi of Babylon, whose code, carved in stone for all to see, declared that justice must be accessible and visible. From contracts and wages to family law, his code wove law into daily life. Notably, it institutionalized the idea that rulers are not above the law—they are bound by it.

🏺 Egypt: The Sacred Geometry of Ma’at

To rule in ancient Egypt was to walk a moral tightrope. Pharaohs were earthly stewards of Ma’at—a cosmic order that balanced truth, justice, and reciprocity. Power was both political and spiritual, and its abuse could imperil the entire realm.

⚖️ Pharaoh Horemheb, after a period of religious upheaval, led legal and administrative reforms to restore Ma’at. He prosecuted corrupt officials, reestablished fairness in tax collection, and emphasized the ruler’s duty to the people, not just the gods.

Rather than fear, Egypt’s governance cultivated respect—justice was not only enforced, it was believed in.

🌊 Indus Valley: The Quiet Precision of Civic Design

In contrast to the grandeur of kingship, the Indus Valley Civilization (2600–1900 BCE) whispers a different legacy—one of organization without opulence. Cities like Mohenjo-Daro reveal meticulous urban layouts, advanced sanitation, and standardized systems, but no grand palaces or overt temples.

🏛️ The absence of monumental authority suggests a decentralized, perhaps even egalitarian approach to governance. The built environment did the work of justice—every street, drain, and granary a silent commitment to public well-being.

Here, governance may have functioned less through edict and more through design—a civic ethic literally embedded in brick and stone.

🐉 Ancient China: Virtue, Mandate, and Accountability

The Zhou Dynasty’s introduction of the Mandate of Heaven redefined political legitimacy—not as divine inheritance, but as a moral contract. If rulers governed unjustly, they were said to lose the mandate and could rightfully be overthrown.

👑 Duke Zhou, a model of humility and foresight, declined the throne despite having the opportunity to seize it. Instead, he governed as regent, restored order, and shaped political ethics for generations. His example infused Confucian thought with an enduring ideal: that leadership is a moral burden, not a birthright.

☯️ Here, the state became an ethical institution, charged with cultivating harmony—not just obedience.

🏔️ Caral–Supe: Monument Without Militarism

High in the Andes, the Caral–Supe civilization (c. 3000 BCE) built monumental pyramids—but without evidence of warfare, weaponry, or empire-building. Their leadership seems to have rested on cooperation, ecological stewardship, and shared ritual life.

🎶 Amphitheaters, musical instruments, and irrigation networks suggest a society built not on domination, but on cohesion.

🌀 In Caral, power flowed not through conquest, but through the ability to convene, inspire, and sustain balance between society and nature—a vision still radical today.

🪨 Olmec Foundations: Sacred Symbol and Social Order

The Olmec, often considered the mother culture of Mesoamerica, left behind colossal stone heads—believed to depict rulers or revered ancestors. Their massive scale signaled not domination, but symbolic stewardship.

🪶 While we know few names, the enduring architecture, calendar systems, and glyphs point to leaders deeply entwined with cosmic responsibility. Their authority rested on mediating the spiritual and civic worlds, ensuring that rule aligned with divine rhythm.

The Olmec template—blending ritual with rulership—was later inherited by the Maya and Aztec, anchoring centuries of civil-religious systems.

🔁 Ancient Lessons, Contemporary Mandates

From every corner of the ancient world emerges a shared truth: legitimacy must be earned, not seized. Power, unchecked by ethics, corrodes. Leadership, when animated by justice and wisdom, becomes transformative.

💬 Hammurabi’s stone laws echo in today’s constitutions.

⚖️ Ma’at whispers through every call for ethical public service.

🏙️ Mohenjo-Daro’s streets foretell the promise of inclusive design.

🧭 The Mandate of Heaven lives on in the principle that no leader is above accountability.

🌱 Caral’s silent pyramids still call us to harmonize progress with stewardship.

🌟 Conclusion: Civic Memory as Civic Guide

These ancient civilizations were not merely the first to build cities—they were the first to imagine what it means to belong to something larger than oneself. In their myths, laws, and architecture, they sketched the blueprints for moral leadership, social responsibility, and civic imagination.

For students, educators, and advocates shaping the future, these stories are more than historical episodes. They are ethical wellsprings—reminding us that governance is not just administration; it is an act of conscience.

And the oldest stories, it seems, are still teaching.

Retired Senior Citizen

Teshie-Nungua

[email protected]

By Dawn –

For students, educators, and advocates of history, ethics, and civic transformation