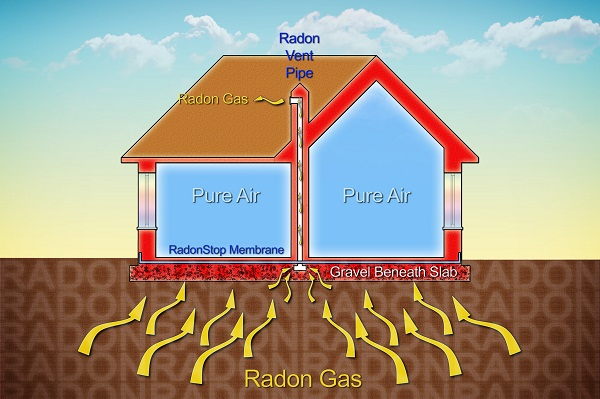

Radon is an invisible but dangerous radioactive gas that seeps from the ground into buildings

Radon is an invisible but dangerous radioactive gas that seeps from the ground into buildings

Radon is an invisible but dangerous radioactive gas that many Ghanaians are unaware of. It seeps from the ground into homes and buildings, and long-term exposure can lead to serious health risks, including lung cancer. In this interview, we speak with Charlotte A Annan, a Ghanaian PhD candidate in Geochemistry at Georgia State University, whose research explores how radon behaves in soils and what that means for public health in Ghana. With academic experience spanning Ghana, Belgium, and the United States, Charlotte is passionate about using science to inform policy and raise awareness about overlooked environmental threats like radon.

1. What inspired you to focus on radon?

My interest in geochemistry began during my Earth Science studies, where I became fascinated by how natural processes impact the environment. Later, I wanted a PhD topic that connected science with real-world health. My advisor introduced me to radon in soils. At the time, I barely knew about it, but when I learned that this odourless gas causes lung cancer and is rarely talked about, I knew it was worth exploring. The mix of science, health, and practical relevance pulled me in.

2. What does your research involve?

I study how radon behaves in different soil types — especially the layers or “horizons” beneath the surface. I’m looking at how soil properties like texture, chemistry, and moisture affect radon release and movement. Understanding this helps assess the risk of radon exposure, which is especially important in areas where people live or work.

3. Why is radon a concern in Ghana?

Some areas in Ghana—such as parts of Greater Accra, Eastern, and Ashanti regions — sit on granite bedrock or fractured formations that naturally release radon. But testing and awareness are limited, so people may unknowingly live in high-risk homes. Radon has no smell or colour, so the only way to know is to test.

4. What can people do to protect themselves?

Testing is the first step. In countries like the U.S. and Canada, people use small test kits or digital radon monitors. If high levels are found, ventilation, sealing floor cracks, or installing mitigation systems can help. Ghana can create a similar framework if we raise awareness and support low-cost testing, especially in schools and homes.

5. Is testing available in Ghana now?

It’s still very limited. But the process is simple and cost-effective if properly supported. With collaboration between scientists, the government, and public health experts, Ghana can develop its own radon monitoring programmes.

6. Why is public education important to you?

Because without awareness, science can’t create change. I’ve written articles and shared my research through various platforms to help inform the public. I believe small efforts—like this interview—can help people take action to protect themselves and their families.

7. What advice would you give to young girls who want to pursue science?

Fall in love with learning. I genuinely enjoy understanding how things work, and that keeps me curious and motivated. You don’t have to be perfect—you just have to be willing to grow. Work hard, ask questions, and surround yourself with people who support your goals.

8. What’s your long-term vision for your work?

I want to help create systems that detect and reduce environmental risks—especially invisible ones like radon. Whether through research, policy, or outreach, I hope my work will contribute to healthier, safer communities.

By Alice Frimpong Sarkodie

(Ms. Sark LifeCoach)

Director, Nobel Heights School

Executive Secretary, Women’s League Platform

Co-Founder, Women Leaders International Ghana