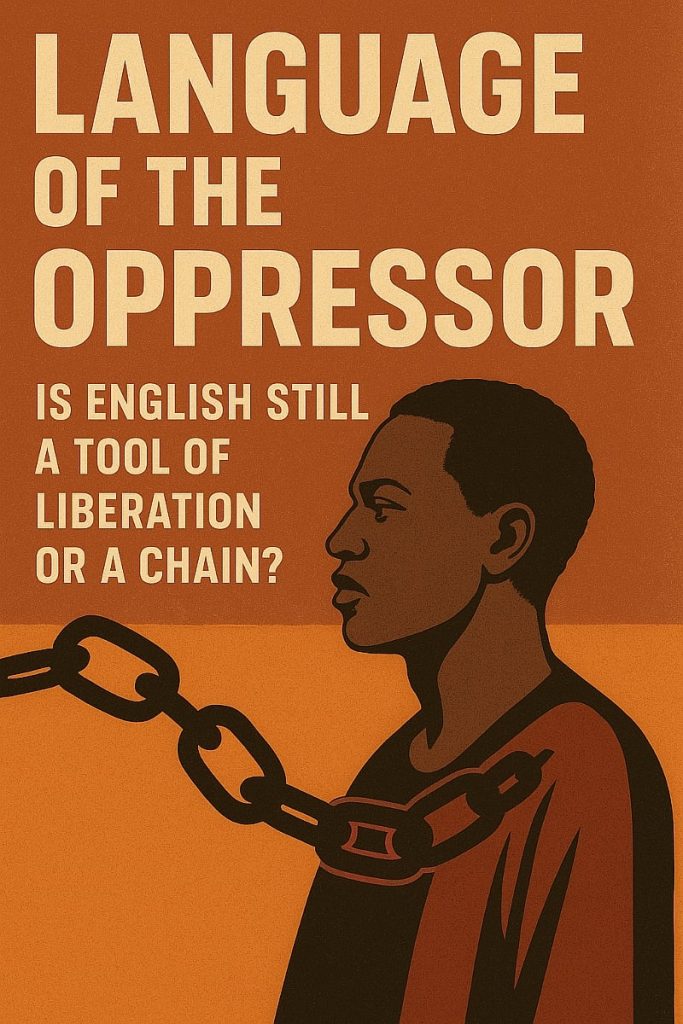

Language is never neutral. It is either a bridge or a barricade, a dagger or a dove. In the African context, the English language occupies a controversial throne revered by some as the path to global relevance and cursed by others as the echo of colonial domination. But as Africa marches deeper into the 21st century, a pressing question emerges: Is English still a tool of liberation, or has it become an invisible chain binding African minds to foreign ideals?

The Irony of Liberation Through Conquest

English was not gifted to Africa; it was imposed. From Lagos to Lusaka, the arrival of English marked not the dawn of enlightenment but the sunset of indigenous voices. African children were flogged for speaking their mother tongues. Traditional knowledge systems were mocked, marginalized, or erased. The oppressor’s language was not just about communication, it was about control. By naming our rivers, redrawing our borders, and rewriting our stories in English, the colonizer not only conquered our lands but our minds.

Yet, in an ironic twist of history, English today serves as the main medium through which Africans challenge global injustice. From the speeches of Chinua Achebe and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o to the writings of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Tsitsi Dangarembga, English has been weaponized to expose the very systems it once upheld. It is through English that African scholars gain access to international platforms, that African entrepreneurs attract investment, and that political activists mobilize global solidarity.

The Two-Edged Sword

English, then, is a double-edged sword. It opens doors to diplomacy, science, literature, and commerce. It allows a Kenyan to negotiate in Beijing, a Nigerian to publish in Paris, and a Ghanaian to lecture in New York. For many young Africans, English is not just a language, it is a survival strategy.

But at what cost?

Each time an African child is punished for not speaking “good English,” a piece of their cultural self is quietly buried. Each time an interview board laughs at a candidate’s local accent, dignity is eroded. Each time a traditional language is excluded from classrooms, a lineage of wisdom begins to wither. In many African nations, fluency in English still determines access to jobs, scholarships, and respect. The colonial hierarchy lingers only now, it hides behind grammar.

The Silent Death of Indigenous Languages

Over 2,000 languages are spoken in Africa, yet many are endangered. Not because they lack beauty or depth, but because they lack prestige in a world that measures intelligence by how “fluent” you are in a foreign tongue. The loss of a language is more than the loss of words, it is the loss of memory, proverbs, poetry, philosophy, spirituality, and the worldview of a people.

What happens when a people can no longer pray, joke, or dream in their native tongue? They begin to think like outsiders, even while living at home.

Reclaiming the Narrative

The answer is not to abandon English. That would be impractical and even self-defeating. Instead, we must domesticate it. As Achebe once said, “Let us make it carry the weight of our African experience.” Let English walk barefoot through African villages. Let it carry African idioms, wear African proverbs like agbada, and kneel before elders. Let it be taught alongside Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, Swahili, Shona, Zulu, Wolof, and Fulfulde.

Let bilingualism or even multilingualism be the new standard of literacy.

We must raise a generation of Africans who are equally proud to write an academic thesis in English and recite ancestral chants in their native languages. We must teach children that speaking fluent Hausa is no less intellectual than speaking fluent English. We must insist that our cultures, our histories, our voices, deserve more than translation.

Conclusion: The Power of Language in African Hands

So, is English a tool of liberation or a chain?

It is both. And neither. It is only what we make it.

English is not the enemy. Submission is. Cultural inferiority is. Forgetting is.

Let us wield English like the sharpened hoe of an African farmer not to uproot our heritage, but to plant our truth in global soil. Let us use it to shout, not whisper. To remember, not erase. To liberate, not to bind.

Because the real power does not lie in the language itself but in whose story it tells, and how it is told.