In an era of precarious global alignments and rising regional instability, the Strait of Hormuz—a slender maritime corridor linking the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea—has once again reemerged as a flashpoint for energy geopolitics. Following Iran’s recent threat to close the strait if the United States escalates its support for Israel in an ongoing regional war, concerns over the security of global energy supplies and economic stability have reached a critical juncture. While energy analysts caution that a complete blockade remains unlikely, the specter of disruption alone has triggered waves of apprehension across diplomatic and commercial circles.

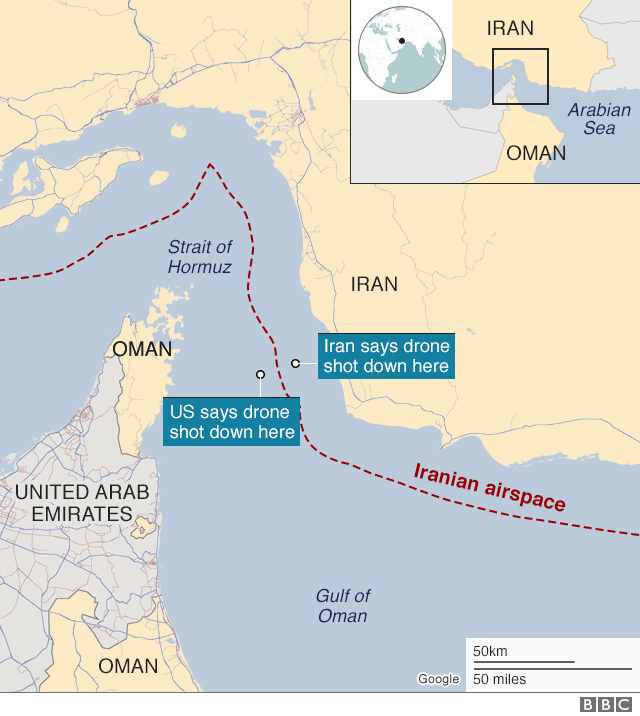

Located between Iran to the north and the United Arab Emirates and Oman to the south, the Strait of Hormuz is only 33 kilometers wide at its narrowest point. Yet, this seemingly modest channel accommodates the transit of nearly one-fifth of global oil exports and the totality of Qatar’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) shipments—an energy lifeline that directly connects the economies of the Middle East to Asia, Europe, and beyond. As political scientist Kenneth N. Waltz once observed in Theory of International Politics (1979), chokepoints such as these symbolize the structural constraints that bind nation-states into asymmetric interdependence, where geography becomes both a strategic asset and a vulnerability.

The Geopolitical Stakes of a Chokepoint

The Strait of Hormuz is more than a logistical corridor; it is an emblem of global energy interdependence. Iran’s declaration that it might obstruct this waterway—framed as a retaliatory measure should the United States formally join the conflict—has raised alarms about the broader implications of a prolonged Middle Eastern crisis. “It’s the bloodstream of global energy,” asserts Dr. Mevlut Tatliyer of Marmara University. “If you block the flow, the whole body weakens.”

A disruption of such magnitude would ripple across financial markets, destabilize oil prices, and exacerbate global inflationary pressures. The International Energy Agency (IEA), in its World Energy Outlook 2023, underscores that even temporary obstructions in Hormuz would produce “severe consequences” for the oil and gas market due to the narrow margin of supply elasticity. This echoes the concerns raised in Daniel Yergin’s The Prize (1991), which chronicled the 1980s Tanker War as a sobering case study of how geopolitical conflicts can reverberate through energy infrastructures and commodity markets.

Historical Precedents and the Lessons of the Past

The Strait has a turbulent history of being entangled in conflict. From the “Tanker War” during the Iran-Iraq conflict of the 1980s to the 2023 U.S. Navy interventions to thwart Iranian seizure of oil tankers, Hormuz has recurrently played host to skirmishes with global implications. Past incidents—from the 1988 downing of Iran Air Flight 655 by a U.S. cruiser to the seizure of a South Korean-flagged tanker in 2021—illustrate the fragility of peace in this region. As Michael Klare noted in Resource Wars (2001), such flashpoints often become arenas of contestation not just over territory but over control of vital flows of energy and capital.

Quantifying the Risk: Production and Passage

The scale of vulnerability is staggering. As of May 2025, Saudi Arabia produced approximately 9.18 million barrels of oil per day, followed by Iraq with 3.9 million barrels, Iran with 3.3 million barrels (of which only 1.4 million are exported), and Kuwait and the UAE combining for 5.3 million barrels. Collectively, this amounts to over 21 million barrels daily—most of which traverse the Strait of Hormuz.

Even Saudi Arabia, with an alternative pipeline route to the Red Sea, can only reroute a third of its output. This leaves approximately 17 million barrels per day dependent on Hormuz, according to Oguzhan Akyener of Türkiye’s Energy Strategies & Politics Research Center (TESPAM). The Handbook of OPEC and the Global Energy Order (Goldthau, 2012) similarly asserts that no alternative route possesses the capacity to absorb the entirety of Gulf-origin energy exports, revealing systemic inflexibility in energy logistics.

The risks are not confined to oil. Qatar’s entire LNG exports pass through Hormuz, making Asia—particularly energy-intensive economies like China, Japan, India, South Korea, and Pakistan—acutely vulnerable. As Amy Myers Jaffe observes in Energy’s Digital Future (2021), the regional fragmentation of natural gas markets, unlike the fungibility of oil, renders LNG supply chains significantly harder to reconfigure in crisis situations.

Economic Domino Effect: From Regional Shock to Global Recession

The economic consequences of a closure—even if temporary—could be monumental. Brent crude oil prices could spike well past $100 per barrel, reaching up to $110 in prolonged disruptions, while even a minor skirmish might lead to a psychological price surge to $85–$90. This would evoke memories of the 1973 oil embargo and the 2008 financial crisis, both of which were marked by energy-triggered inflation.

Tatliyer emphasizes that energy shocks do not remain confined to the energy sector. “When energy prices spike, it becomes a global inflation story,” he states. “And when inflation rises, it affects every sector—food, transport, and manufacturing.” Such interconnected inflationary shocks are explored in Joseph Stiglitz’s Globalization and Its Discontents (2002), where he identifies energy volatility as a primary cause of fiscal stress for emerging markets.

Some forecasts predict a potential drag of 1–2 percent on global GDP should the Strait be closed for an extended period. The increase in shipping costs, insurance premiums, and commodity prices would be immediate and widespread. Industries relying on just-in-time supply chains, such as automotive and electronics manufacturing, would be particularly exposed—recalling the global semiconductor shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic, as analyzed by Baldwin and Evenett in Revitalising Multilateralism (2021).

Strategic Hesitations and Diplomatic Realities

Despite its provocative rhetoric, Iran is unlikely to initiate a full-scale closure of Hormuz. Not only would such a move isolate Tehran diplomatically, but it would also alienate key allies—most notably China, Iran’s largest trading partner and a state deeply dependent on Gulf energy flows. As Henry Kissinger articulated in World Order (2014), international norms around freedom of navigation represent a red line for maritime powers, and any breach invites multilateral retaliation.

OPEC’s decision to increase production starting in July 2025 appears to be a preemptive hedge against possible market volatility. This echoes arguments in Jeff Colgan’s Petro-Aggression (2013), which links energy exports and conflict behavior, noting how oil-exporting states often modulate output as a tool of strategic signaling.

Structural Fragility and Global Interdependence

Global energy markets remain structurally fragile. Of the 101 million barrels of oil produced daily worldwide, over 20 percent of the seaborne trade passes through Hormuz. A prolonged closure would not only constrain energy supplies but disrupt trade flows of petrochemicals, consumer goods, and raw materials destined for both Asia and Europe. The resultant inventory shortages would be most visible in industries like pharmaceuticals, textiles, and electronics, all of which rely on finely calibrated logistics chains.

In The Collapse of Western Civilization (Oreskes & Conway, 2014), the authors warn of the systemic risks posed by over-reliance on vulnerable infrastructures. Hormuz encapsulates such fragility. Its closure—even speculative—can rattle stock exchanges, inflate freight costs, and spark diplomatic crises.

The Strait as Metaphor and Warning

Ultimately, the Strait of Hormuz is not merely a maritime corridor. It is a geopolitical metaphor—a slender bottleneck through which the arteries of globalization pulse. Its strategic location makes it both a blessing and a burden, a space where economic rationality clashes with political brinkmanship.

The 2023 and 2025 incidents of Iranian attempts to seize tankers, alongside U.S. interventions to uphold freedom of navigation, demonstrate how easily escalation can be triggered. As Barry Buzan’s People, States and Fear (1991) suggests, threats to national security today are increasingly transnational in origin and require systemic approaches rather than regional containment.

In the absence of robust multilateral crisis management mechanisms, any disruption in Hormuz—be it a tactical skirmish or a strategic standoff—has the potential to realign global energy markets, reshape diplomatic alliances, and precipitate economic slowdowns. As the world stumbles through inflation, fractured supply chains, and volatile diplomacy, the Strait of Hormuz remains a reminder of how fragile our interconnected world truly is.

References

Waltz, Kenneth N. Theory of International Politics. McGraw-Hill, 1979.

Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. Free Press, 1991.

Klare, Michael T. Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict. Metropolitan Books, 2001.

Goldthau, Andreas. Handbook of OPEC and the Global Energy Order. Routledge, 2012.

Jaffe, Amy Myers. Energy’s Digital Future. Columbia University Press, 2021.

Stiglitz, Joseph E. Globalization and Its Discontents. W. W. Norton, 2002.

Baldwin, Richard & Evenett, Simon. Revitalising Multilateralism. CEPR Press, 2021.

Kissinger, Henry. World Order. Penguin Books, 2014.

Colgan, Jeff D. Petro-Aggression: When Oil Causes War. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Oreskes, Naomi & Conway, Erik. The Collapse of Western Civilization. Columbia University Press, 2014.

Buzan, Barry. People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-Cold War Era. ECPR Press, 1991.