The Real Cost of Rain

The Real Cost of RainNavigating the Urban Storm

“A city that fears the rain is a nation unprepared for its own future. In the flood, every drop becomes political—and every silence, a scandal.” — Bismarck Kwesi Davis

The Storm Before the Storm

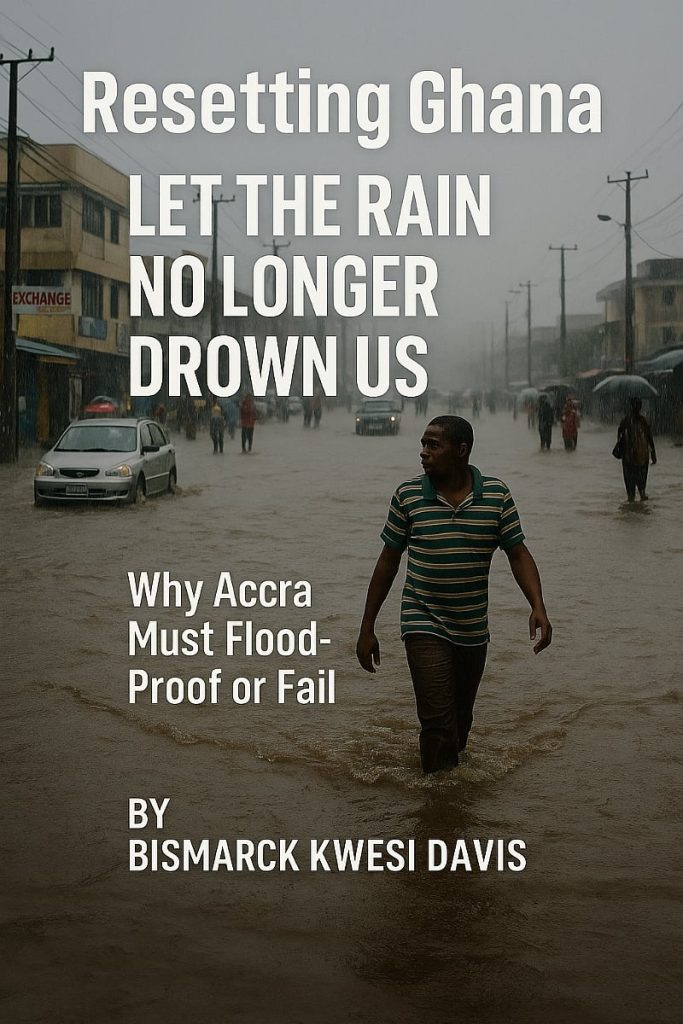

Between May and July each year, the clouds that loom over Ghana’s southern corridor do not merely herald rain; they threaten catastrophe. In the commercial arteries of Kaneshie, Spintex, Circle, and Kasoa, flash floods transform roads into rivers, shops into ponds, and homes into boats of despair. These are not natural disasters. These are man-made crises—engineered by negligence, poor urban planning, institutional disconnection, and reactive policies.

This article moves beyond episodic outrage. It proposes a bold, data-driven environmental strategy with urban resilience at its core—backed by legislative clarity, real-time recovery systems, and institutional accountability. The time has come to elevate flood discourse from emotional headlines to strategic transformation—anchored in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Ghana’s commitment under the 2030 Agenda.

I. Counting the Cost – A Decade of Urban Flood Impact (2015–2025)

According to the National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO) and corroborated by findings from the Ministry of Works and Housing, flooding in Greater Accra alone has cost the Ghanaian economy over GHS 6.3 billion (USD 510 million) over the past decade (NADMO, 2023; MWH, 2024).

Sector Affected Estimated Economic Loss (2015–2025) Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) GHS 1.8 billion Public Infrastructure GHS 2.1 billion Residential Property Damage GHS 800 million ECG Disruption & Grid Failure GHS 520 million Public Health (e.g., cholera) GHS 360 million Emergency Relief (NADMO) GHS 720 million

Beyond economics, the psychological trauma—especially in low-income settlements—is devastating: loss of school days, job insecurity, internal displacement, and erosion of public trust. Projections from UN-Habitat estimate that, without intervention, flood-induced losses in Ghana could surpass GHS 12 billion by 2030, accounting for 2.5–3% of annual GDP (UN-Habitat, 2023).

II. Future-Proofing Ghana – The 2025–2030 Mandate

To reverse this descent, Ghana must align flood resilience with four key SDGs:

SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities SDG 13: Climate Action

A comprehensive five-year flood-resilience investment strategy—estimated at GHS 4.5 billion—could reduce economic loss by over 60%, while protecting over 2.4 million urban residents. Strategic recommendations include:

Installation of smart drainage systems with AI-monitored overflow points. Construction of elevated road networks in flood-prone zones (e.g., Odawna, Alajo). Relocation of ECG transformers and substations to climate-secure elevations. Deployment of community-based microgrids for power backup. Nationwide pre-flood dredging operations, budgeted annually.

III. Institutional Synergy – Making Agencies Flood-Smart

NADMO

Must evolve into a Flood Intelligence Bureau with GIS flood-zone maps, predictive analytics, and district-level drills ahead of the rainy season.

Ghana National Fire Service (GNFS)

Should be equipped with amphibious vehicles, drone surveillance, and swift-water rescue units. These are no longer luxuries—they’re lifesaving assets.

Ghana Meteorological Agency (GMet)

Requires modern radar and hyper-local alert systems, integrated with telcos for real-time SMS flood warnings. Financing should be anchored in the national climate adaptation budget (World Bank, 2022).

Over the last decade, urban flooding has cost Ghana over GHS 6.3 billion in lost infrastructure, health emergencies, property damage, and energy disruptions. Small businesses have folded under rising water. Public hospitals and schools have shut their gates due to inaccessible roads. More tragically, children have died in open drains and mothers swept away while commuting (NADMO, 2023; MWH, 2024).

And this is only the beginning. Without urgent reforms, Ghana could lose over GHS 12 billion to floods by 2030—enough to fund two major hospitals, five motorways, and a national housing project. The floods aren’t just about water. They’re about leadership, systems, and the price of delay.

Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG)

A national audit of flood-exposed transformers is urgent. GIS mapping must drive relocation. All new infrastructure should adhere to climate-smart electrical standards.

Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL)

Floods contaminate freshwater systems. GWCL must:

Install flood-resistant treatment plants and sealed pipe chambers. Monitor contamination using real-time AI water sensors. Provide safe water distribution tanks during and after floods. Conduct quarterly water safety audits in high-risk communities.

IV. Legislative Urgency – Enacting the Flood & Clean Water Resilience Act (2025)

To consolidate reform, Parliament must introduce the:

National Urban Flood Control & Clean Water Resilience Act (2025)

Core Provisions:

Mandatory flood-risk assessments for all public and private projects. Green taxes on high-risk urban development, International climate adaptation grants, Disaster risk insurance schemes with partners like the African Risk Capacity (ARC). Empower local assemblies to enforce urban zoning and prosecute violations. Formal inclusion of ECG and GWCL in Metropolitan Flood Planning Units. Institutionalization of annual “Pre-Flood Season Reports” to Parliament. Establishment of a Climate & Urban Resilience Fund (CURF)—funded through:

From Excuses to Execution

What Must Be Done — Not Tomorrow, Now

Ghana doesn’t need another press conference. It needs a Flood Control and Clean Water Resilience Act. This law must do three things:

Enforce smart urban planning—No more building in watercourses, no more excuses. Invest in technology—AI-based flood sensors, mobile water safety alerts, GIS maps, and pre-flood dredging must become standard. Fund institutional synergy—NADMO, ECG, GWCL, Fire Service, and local assemblies must act as one unit, not separate bureaucracies.

Let’s be clear: NADMO must move from being reactive to predictive. The Fire Service must train in urban flood rescues. ECG must relocate flood-prone transformers. GWCL must guarantee clean water even during floods—not murky liquid that leads to cholera and shame.

Let the Taps Flow — Not the Gutters

Floods don’t just knock down homes—they pollute water systems. In many parts of Accra, residents are forced to choose between paying vendors for sachet water or drinking possibly contaminated tap water. This must end. GWCL must install flood-proof water purification plants and use AI sensors to detect sewage cross-contamination in real time. Every rainy season should come with a public assurance report on tap water quality—before, during, and after the rains.

It’s Not the Rain — It’s Us

If Singapore can handle typhoons and The Netherlands can live below sea level, Ghana can handle rain. We just need courage, coordination, and legislation.

We don’t need more committees. We need consequences for those who block drains, issue illegal permits, and underfund resilience projects.

Let the 2025 budget reflect this urgency. Let Parliament rise above politics. Let ministries stop overlapping and start coordinating. And let Accra finally become what it should be—a proud capital, not a floodplain in disguise.

The Time Is Now

We can’t keep praying the rains away. We must prepare. We must legislate. We must lead.

Let this rainy season not drown another child or another dream.

Ghana is no longer in a place where rainfall can be considered a surprise. It is a seasonal certainty, and the consequences of inaction are no longer tolerable. What must change is not just the drain, but the mindset. Rain must not remain a national threat. It must become a test we are designed to pass.

As the urban storm brews once again, let us not surrender to helplessness. Let this rainy season mark the shift—from panic to planning, from loss to legislation, from delay to design.

“The time to flood-proof Accra was yesterday. The time to legislate was last year. The time to act is now.” — Bismarck Kwesi Davis

References

Ministry of Works and Housing (MWH). (2024). Annual Infrastructure Risk Assessment Report. Accra, Ghana. National Disaster Management Organisation (NADMO). (2023). Flood Impact Analysis: Greater Accra 2015–2023. UN-Habitat. (2023). Ghana Urbanization Review: Climate Vulnerability & Resilience. World Bank. (2022). Climate Risk Profile: Ghana. Retrieved from https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org Ghana Water Company Limited (GWCL). (2023). Safe Water Audit for Rainy Season Preparedness.African Risk Capacity. (2024). Parametric Insurance Models in West Africa: A Flood Perspective.