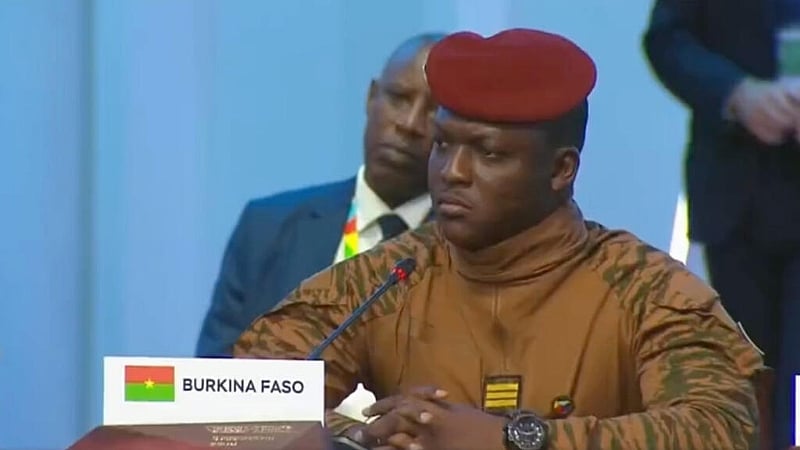

A young Burkinabè soldier revives the Sankara spirit, but can he survive the storms of power and geopolitics?

A New Flame in the Sahel

From the era of Kwame Nkrumah to the tragic fall of Thomas Sankara, Africa’s struggle for authentic sovereignty has always hinged on the rise of visionary leadership—figures who dared to defy the status quo. In an age of global disillusionment, 36-year-old Captain Ibrahim Traoré has ignited fresh hope. Rising from the embattled Sahel in 2022, he speaks a language long missing from African politics: dignity, self-determination, and Pan-Africanism.

But is Traoré a true torchbearer or merely a fleeting fire?

Echoes of Sankara: Revolution Revisited

When Traoré staged a military coup in September 2022, it appeared—at first—like yet another installment in West Africa’s cycle of instability. Yet his swift and bold decisions hinted at something deeper. French troops were expelled, exploitative military accords were terminated, and colonial-era privileges dismantled. In their place, Traoré emphasized national dignity and sovereignty.

Observers could not help but draw comparisons with Thomas Sankara, the “African Che Guevara,” who led Burkina Faso’s most radical transformation in the 1980s before falling to a coup in 1987. Traoré invoked Sankara’s spirit not just in speeches, but in policies. For many Burkinabè, the revolution that was buried decades ago is being exhumed, its heartbeat audible once again in the rhythms of resistance.

Strategy over Symbolism

Yet Traoré is no romantic idealist. He governs amid jihadist violence that has displaced millions and undermined the state’s reach. In seeking solutions, he has turned eastward—not for ideological alignment, but pragmatic support. Russia has emerged as his chief ally, providing military equipment, grain, security personnel, and the promise of a nuclear power plant.

Some hail this as geopolitical realignment; others see the risk of dependency trading one power for another. The reopening of the Russian embassy after three decades and the arrival of Russian troops to protect Traoré personally underscores both his vulnerability and his strategic calculations.

Where Sankara prioritized ideology and radical autonomy, Traoré seems to lean on realism—rejecting Western aid tied to structural adjustment but embracing bilateral partnerships that promise tangible results. Gold refineries have been established, national infrastructure projects launched, and GDP growth—modest but notable—has begun to turn heads.

The Continent Is Watching

Beyond Burkina Faso, Traoré’s rise has stirred the imagination of a broader Pan-African audience. In Mali, Niger, and Guinea, leaders speak in similarly defiant tones. Across West Africa, young people chant Traoré’s name alongside Sankara’s and Nkrumah’s. Social media pages are adorned with his images. Songs, graffiti, and speeches celebrate a new resistance.

But admiration is not accomplishment.

Symbolism can only go so far without institutional change. Traoré must now deliver on the tough, less glamorous tasks of governance: strengthening education, restoring public health systems, reviving agriculture, and building judicial integrity. These are the nuts and bolts of revolution—not the poetry, but the plumbing.

And history offers a cautionary tale: charismatic leaders often falter when state institutions remain weak, civil society is sidelined, and checks and balances are ignored. The very forces that lifted Sankara were the same ones that abandoned him when the international tide turned.

Between Hope and History

Africa does not suffer a shortage of brave men; it suffers a shortage of systems that protect and sustain them. Traoré’s greatest test is not in his speeches or his alliances—it will be in how he governs over time. Will he build institutions that outlast him? Or will he follow the fate of so many who burned brightly but briefly?

The challenge is magnified by geopolitics. Traoré’s critique of Western imperialism is not unfounded. Burkina Faso, like many African nations, has suffered from exploitative trade, meddling interventions, and elite capture. But turning east does not absolve him of the responsibility to maintain independence. Russia, too, has its interests. The task ahead is to extract benefits without surrendering sovereignty.

The People Must Rise Too

Traoré may be a symbol, but he cannot carry the revolution alone. True transformation will depend on the vigilance of Burkinabè citizens, the energy of youth movements, the clarity of intellectuals, and the organization of civil society. The diaspora must add its voice, not as cheerleaders, but as critical allies.

We must be wary of cults of personality. Sankara taught us that revolutions belong to the people, not to individuals. As Traoré walks this fragile path, Africa must rally—not around him as a messiah, but around the mission he claims to represent.

Conclusion: Not Just a President—A Possibility

In Ibrahim Traoré, Africa sees more than a man. It sees a mirror to its past and a window to its potential future. He is young, imperfect, and untested in the long arc of governance. But in a continent worn down by betrayal, his defiance offers a glimpse of hope.

Hope, however, is not a promise—it is a question.

Will this new flame burn long enough to light the way forward? Or will it flicker, as so many before it have, consumed by the winds of power, foreign manipulation, or internal decay?

Only time—and the people—will tell.