Asante trophy head looted by the British in the 1874 invasion of Kumase, Ghana, now in Wallace Collection, London.

Asante trophy head looted by the British in the 1874 invasion of Kumase, Ghana, now in Wallace Collection, London.‘Colonialism imposed its control of the social production of wealth through military conquest and subsequent political dictatorship. But its most important area of domination was the mental universe of the colonised, the control, through culture, of how people perceived themselves and their relationship to the world. Economic and political control can never be complete or effective without mental control. To control a people’s culture is to control their tools of self-definition in relationship to others.’

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature

Just in time for the International Museum Day, 18 May 2025, a significant event in the global museum community, the Director of the British

Museum, Nicholas Cullinan, reiterated in an interview published in The Times of 10 May 2025 the policy of the British Museum not to restitute any artefacts from its collections and declared that he would not try to take any steps towards making make restitution possible. (1) Nicholas Cullinan told The Times in an interview that: “I could make lobbying to get the act changed my sole focus, but that seems mad, and it may not be the right thing.”

Concerning the Parthenon Marbles described by Cullinan as “talismanic objects of the British Museum,” the Director added that there is a plan in the making,’ an innovative partnership with Greece where we would lend things and they would lend things back. We can share knowledge and opportunity rather than debate ownership.” So, it is only lending to Greece that is envisaged. We lend to you; you lend to us; we lend to you; you lend to us. Who is the owner? The English language has a remarkable ability to conceal things in broad daylight, especially when used by native speakers.

The Director also ruled out any future restitution of the Benin Bronzes. He repeated the usual alibi: “We have a fantastic relationship with MOWAA [the

Museum of West African Art], the new museum of art in Benin Cit

y, and we are sharing a joint archaeological excavation. They might want to borrow other things, but what we can’t do is deaccession.”

The British Museum will continue to offer loans to those seeking restitution. “The British Museum is about connecting countries rather than putting up barriers. This is a global museum for everyone and we’re not going to be embarrassed about that anymore. We are going to foster collaboration around the world.”

We do not know in what mood the British Museum director gave the interview to The Times, nor what his intentions were. If the museum director intended to discourage future requests for restitution from the British Museum, he is surely mistaken. The Asantehene, who recently presented a request for the restitution of the Asante gold artefacts looted by the British during the 1874 invasion of Kumase, Ghana, would not be discouraged by Cullinan’s interview. The Asante monarch gave a lecture at the museum, which was opened by Nicholas Cullinan, in which the Asantehene explained the reason the Asante accepted a loan of their artefacts. The loan was accepted as offering an opportunity for further negotiations on an eventual restitution. (2) Similarly, the Oba of Benin will not relinquish the demand for the restitution of the Benin Bronzes that the British looted during the nefarious Punitive Expedition of 1897, a violent and destructive military campaign. Greece, which has been fighting for a long time to recover the Parthenon Marbles that Lord Elgin shipped to Britain under disputed circumstances, will surely not be discouraged by this recent interview. The Director’s preference for loans rather than restitution of the looted objects cannot change the course of history. In our time, it is accepted that artefacts that were looted with violent military force during the colonial rule or under dubious circumstances must be returned.

France, the imperialist sister of Britain, which also systematically robbed Africans of their cultural treasures as well as other resources, has started returning African artefacts as recommended by the Sarr-Savoy Report (2018) commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron, who condemned colonialism as a crime against humanity. Germany, which plundered African artefacts on her own but purchased the Benin artefacts from the British at various auctions, restored to Nigeria the legal rights to 1,300 artefacts. Even in Britain, institutions such as Jesus College, Cambridge, the University of Aberdeen, and the Horniman Museum have all restituted Benin artefacts.

Cullinan did not say anything that the museum’s previous directors had not said. What then motivated this irritating negative statement? Is it possible that the new Director was trying to assure groups and individuals who oppose restitution that he was not about to dismantle this citadel of looted goods? (3)

One advantage of this rejection of restitution is that it confirms very clearly what many have always suspected and said for a long time. If there is no

restitution from the British Museum, it is mainly because none of its directors has been keen on restitution. The argument often heard that the British Museum Act 1963 prevents the museum from returning objects is now shown not to be the actual reason. (4)

Another aspect of the Director of the British Museum’s statement is that it underscores the need for political action. Claimants of restitution now know, beyond all reasonable doubt, that they cannot obtain any help from the Director of the museum, which holds more than thirteen million objects, mostly looted. The demanders will have to address themselves to the right institution, namely the British Parliament. This reinforces the view that restitution is a political act that lies with the British Government. It was undoubtedly the British Government that ordered the invasion of Ethiopia, the invasion of Kumase, the invasion of Benin, and the invasion of the Summer Palace in Beijing. The museum only keeps the loot that the army and the soldiers brought back to Britain. With this clarified situation, claimants of restitution should no longer allow the game of ping-pong that the British Museum and the British Parliament used to play. You ask Parliament for restitution, and it directs you to the British Museum, which holds and controls the objects; the museum, in turn, advises you to approach Parliament, which alone has the power to change the law.

The British Museum’s rejection of restitution is a defiant and provocative stance. It is a direct challenge to all those whose precious artworks are housed in the mighty fortress in the heart of London. This defiance should be met with with a renewed determination to secure the stolen treasures. The declaration is a defiance because it speaks directly to all those, including Neil MacGregor, former Director of the British Museum and The Times, who have recently said that it is time to restitute looted artefacts and treasures acquired under dubious circumstances. Macgregor, in his book À monde nouveau, nouveaux musées (2021), argues that the world has changed; the Western world no longer dominates the rest of the world, and museums must adapt their structures and policies accordingly. Supporting the changed views of MacGregor, The Times threw in its support for the return of the Parthenon Marbles to Athens:

‘For more than 50 years, artists and politicians have argued that artefacts so fundamental to a nation’s cultural identity should return to Greece. The museum and the British Government, supported by The Times, have resisted the pressure. But times and circumstances change. The sculptures belong in Athens. They should now return.’ (5)

The Guardian also shared the opinion of The Times. In this regard, the leading British newspapers reflected the opinion of the majority of the British people, who, in all the opinion polls of the last decades on the issue of the Parthenon

Marbles, have overwhelmingly voted for the return of the Greek sculptures to Athens.

The brutal negation of restitution and the statement that no effort will be made to secure a change in the law is a slap in the face of those who assumed that the new British Museum director would join efforts with those seeking a change in the law. Offers to help are superfluous since no attempts would be made in this regard:

“I’m keenly aware that whatever I do, future generations will debate, so I feel more comfortable with loaning items. This collection has been formed over three centuries. It is the world’s greatest collection. I don’t see my job as undoing that.”

The statement by Cullinan is provocative, as it places supporters and demanders of restitution and their activists before an explicit denial of their aims and efforts. They must now be as direct as the museum and define their next steps.

They must now demonstrate and convince their people that they are doing their best to retrieve artefacts that have been missing for a hundred years. They must explain why they cannot take stronger measures to secure restitution. This may be the real benefit of denying restitution directly. Opponents of the British Museum cannot hide behind any false hopes or presumed promises. Demanders of restitution must now show their determination to recover their looted treasures. Those who harbour illusions that recent loans of artefacts will somehow mature into restitutions now know that this will not happen.

Cullinan is right in mentioning that his museum has the most incredible collection. But is it correct to describe this enormous number of stolen artefacts as the ‘greatest collection?’ Would it be more accurate to describe the museum’s collection as the most extensive collection of looted or disputed artefacts?

Geoffrey Robertson has written:”The trustees of the British Museum have become the world’s largest receivers of stolen property, and the great majority of their loot is not even on public display.” (6)

Cullinan, like Jean-Luc Martinez, a former director of the Louvre and author of a recent French report on restitution, does not favour the concept of ownership, as it creates difficulties for ‘universal museums’ when other states and peoples seek restitution of looted artefacts. The directors should be reminded that the notion of ownership applies not only to museum matters but also to society at large. Disparagement of this fundamental concept may affect social order. The museums should not be surprised if individuals who visit the museums also disregard this concept and its general implications.

Cullinan said, “We have a fantastic relationship with MOWAA [the Museum of West African Art], the new museum of art in Benin City, and we are sharing a joint archaeological excavation. They might want to borrow other things, but what we can’t do is deaccession.” This statement should be taken with caution. Nigeria’s relations with the British Museum have been a difficult one that remains quiet because of the restraint exercised by Nigerians and the Nigerian authorities. The Oba of Benin is certainly not impressed with the activities of other entities that aimed to deprive the Oba and the Edo people of their rights to the Benin artefacts. The tension created by different schemes for receiving and guarding returned Benin artefacts, led the former President of the Republic of Nigeria to issue a decree emphasizing that the ownership and guardianship of the precious artefacts belonged to the Benin monarch from whose palace they were stolen in 1897 by the British invasion army. (7)

The demand by the Nigerian Government in October 2021 for the restitution of the Benin artefacts has not been fulfilled. The British Museum, and indeed many Western museums, have not even bothered to answer requests by African governments and peoples for the return of their looted artefacts. So used are Westerners to disrespect Africans that they do not often realize that their conduct is disrespectful. The comments on the homepage of the British Museum do not always tell the whole story. One would not learn from the homepage of the museum that the Oba of Benin, Oba Akenzua II, first requested the return of the Benin artefacts in 1932 and that Oba Erediauwa sent his brother, the late Prince Edun Akenzua, in 2000 to present a plea to the British House of Commons request again the restitution of the looted artefacts. (8)

Cullinan calls his institution a global museum for everyone. The content of his speech and his manner of speaking suggest that he is speaking from a museum that used to be called ‘universal museum’ or ‘encyclopaedic museum.’ In any case, the privileges he claims or assumes for his museum fit perfectly with the privileges and rights that this type of museum asserted when eighteen of the major museums (excluding the British Museum) signed the discredited Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums in 2002.

This type of museum has fallen out of favour for some time now. Still, some people do not recognize that the days of the empire have ended in and that Western museums cannot address peoples and governments as if they were dealing with their subordinates. The British Museum appears not to acknowledge or recognize the independence of countries that were once attacked, invaded, or pillaged by Britain. The paternalistic tone is still there.

Does Cullinan, who calls his museum a global museum for everyone, realize that not everyone can visit London since the British Government, like many former colonial powers, has for some years imposed strict and harsh conditions

for entry visas for visitors from Asia and Africa? Thus, Ethiopians, Ghanaians, and Nigerians who wish to visit the museum in Bloomsbury may not be able to obtain a visa to view the famous African arts there. Western governments have even expelled Africans and others who have valid permission to stay. Museums, such as the Louvre and the British Museum, are only universal in the sense that they house treasures stolen from every part of the world.

The British Museum director pays no attention to the Sarr-Savoy report which recommended the restitution of looted African artefacts. Neither does he consider the historic Declaration by President Macron at Ouagadougou in 2017 that African artefacts must be returned.

I was shocked to read the description of the Parthenon Marbles as ‘talismanic objects’ by the Director of the British Museum. My Oxford Advanced Learners Dictionary of Current English (Eighth Edition) defines a talisman as an ‘object that is thought to have magic powers and to bring good luck.’ We do not know whether those at the British Museum entertain such beliefs. I had such a belief when I was twelve years old but abandoned all such illusions when I learned there was no talisman against colonialism. Given the circumstances under which Lord Elgen had the Parthenon Marbles removed from Athens to England, it seems strange to hope that they will bring luck to those who stole them. What is the morality here? How can we expect stolen objects to bring luck to the thief? How many such talismanic objects are there in the British Museum? Ten thousand, twenty thousand?

Members of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles (BCRPM) have stated in a letter to the Times that ‘ Along with the majority of the British public (according to a recent survey), we hold that the Parthenon Sculptures in the British Museum are part of a unique work of international significance and should be reunited with those remaining in Athens. There they are displayed in full view of the building for which they were originally carved. It was dismaying to read the implications of the Director’s description of the sculptures as “…talismanic objects of this museum.” It has been proved that no official permission was granted to Elgin to remove the sculptures, all prized with enormous violence from the face of the temple. These stolen goods were then shipped to the UK for decorating Elgin’s own home. A talisman is something that brings good luck. How can stolen goods bring good fortune to any institution? [ The Times did not print these two lines]’ (9)

The British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles has described the British Museum’s decision not to return, but only to loan, the Parthenon Marbles as a ‘diplomatic tragedy.’ The tone of Cullinan’s interview

comes across as one person commanding others rather than seeking cooperation and harmony.

Cullinan’s will to cooperate is announced with the same determination as the decision not to restitute artefacts. Arrogance and paternalism are apparent in the statement of the museum director, who oversees the most extensive collection of cultural artefacts looted from other peoples. The tone and context of the speech may be even more important than the words when we consider the long history of the museum’s persistent denial of any obligation, legal or moral, to return the empire’s loot and the current readiness of other former

colonial powers to return looted artefacts.

Now may be the time to start preparing for an International Conference on Restitution of Cultural Artefacts, with the support of United Nations/UNESCO, to define and lay down general principles that should govern the issues of restitution that have emerged in the last decades, especially since the Ouagadougou Declaration by President Emmanuel Macron in 2017. Many governments, institutions, and scholars have expressed views on these issues which will enable the international community to find acceptable solutions to the difficult issues of restitution. Culture should not become synonymous with conflict.

‘The question of the meaning of the ‘Benin bronzes’ or ‘Elgin Marbles’ in London – 1900 or 2000 – is inseparable from the issue of British attitudes towards Africa and the Orient as sites, once for direct military and political colonisation, and now for their post-imperial economic exploitation and indirect manipulation. To return them would imply the belief, on the part of the British authorities, that the peoples of those parts of the world were now capable of competently looking after artefacts that were removed ostensibly o the grounds that the local inhabitants were unfit, because of the ‘degeneration’ of their societies, to act as their curators. Their return would also imply admission of their illegal possession by the Britisj5sh. Both implications remain largely unthinkable because post-imperial racism continues to be a highly significant aspect of British foreign policy. Though British society may be

relatively ‘multicultural’ now, its ruling elite, like that of the US, is still predominantly white, middle-class and male.’

Jonathan Harris (10)

NOTES

1. //www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/2025/05/bm-director-

rules-out-restitution-as-he-outlines-plans-to-foster-collaboration/ https://www.thetimes.com/culture/art/article/inside-the-british-museum-stolen- treasures-and-a-1bn-revamp-wp2zwcs53

https://restitutionmatters.org/news-item/bm-director-rules-out-restitution/ https://www.thetimes.com/culture/art/article/inside-the-british-museum-stolen- treasures-and-a-1bn-revamp-wp2zwcs53

Outcry over Parthenon sculptures ‘Loan’ as permanent return appears unlikely https://greekcitytimes.com/2025/05/14/parthenon-sculptures-return/ K. Opoku, How Long Will the British Government And the British Museum Resist Calls for Changes In Restitution Policy? https://www.modernghana.com/news/1135499/how-long-will-the-british- government-and-the-briti.html

K. Opoku, The nature of the rejection of UNESCO mediation https://www.elginism.com/elgin-marbles/the-nature-of-the-rejection-of-unesco- mediation-for-marbles/20150413/7886/

2. K. Opoku, The Asantehene has spoken: Bring back the Treasures the British Army stole from Kumase in 1874 https://www.modernghana.com/news/1337025/the- asantehene-has-spoken-bring-back-the-treasure.html

3. See annex below.

4. K. Opoku, once in the British Museum, always in the British Museum: Is the

de-accession policy of the British Museum a farce? https://www.pacma.org.uk/ligali/pdf/dr_kwame_opoku_analysis_of_british_mu seum_de_accession_policy_110508.pdf

British Museum And Victoria And Albert Museum Loan Looted Asante Artefacts To Asante /Ghana: Where Is The Morality? https://www.modernghana.com/news/1295729/british-museum-and-victoria- and-albert-museum-loan.html

5. K. Opoku, How Long Will The British Government and The British Museum Resist Calls For Changes In Restitution Policy? https://www.modernghana.com/news/1135499/how-long-will-the-british- government-and-the-briti.html

6. The Guardian, British Museum is world’s largest receiver of stolen goods, says QC https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/nov/04/british-museum-is- worlds-largest-receiver-of-stolen-goods-says-qc

Y2IiUxODdnaWI4MDlrLTAwGeoffrey Robertson ,Who Owns History? Elgin’s Loot and the Case for Returning Plundered Treasure, Biteback Publishing,2019. See also Fresh Refutations to Old Objections, The British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles https://parthenonuk.com/refuting-the- bm-s-statements-1

https://www.greece.org/parthenon/marbles-old/support.htm

7. K. Opoku, Does affirmation of the rights of the Oba in Benin artefacts confuse some Western museums? https://www.modernghana.com/news/1227999/does- affirmation-of-the-rights-of-the-oba-in-benin.html The decree which reaffirmed the rights of the Oba in the Benin artefacts looted from the Royal Palace in 1897 seems to have confused some ignorant and not so ignorant persons to affirm that the artefacts were going to a private person. The British Museum and its allies wanted to transfer the ownership of the historic artefacts to a private firm. The Oba has signed an agreement with National Commission on Museums and Monuments for the administration of the Benin artefacts whilst ownership still remains with the Oba as it has been since the 14th Century.

8. APPENDIX 21 The Case of Benin Memorandum submitted by Prince Edun Akenzua

Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport , British House of Commons https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199900/cmselect/cmcumeds/371/371ap 27.htm

9. Returning Marbles to their birthplace, Times Letters https://www.parthenonuk.com/latest-news/981-returning-marbles-to-their- birthplace-times-letters

10. Jonathan Harris, The New Art History-A critical Introduction ,Routledge, London, p.275.

ANNEX

Extracts from The Principles of Restitution, by Trevor Phillips and Lara Brown

The British Museum director or his advisers may have consulted, for example,

The Elgin Marbles Keep, Lend or Return? Sir Noel Malcolm or

The Principles of Restitution, A guide to Stewardship, Policy Exchange, by Trevor Phillips and Lara Brown. We find in the latter publication statements such as:

‘Stewards should conduct a full consultation of their visitors and the wider public before returning an object.

Consultation is only one principle and the results of any consultation should be considered alongside the other principles. If, however, a consultation determines that an artefact is very important

to museum | policyexchange.org.uk Principles for Restitution visitors, or to the broader public, then stewards should be cautious about accepting a claim for restitution.’

P.48.

‘Stewards cannot safely countenance long-term loans to countries which do not recognise the UK’s legal rights to an object. They should also avoid loans to countries where public sentiment strongly opposes the UK’s ownership of the artefact. P.48.

‘Since the Nigerian Government first called for the restitution of the Bronzes, the President of Nigeria has declared that all bronzes returned will be given to the Oba of Benin.’ P. 50.

‘Stewards should consider the future preservation of the object. Is there evidence those making a claim have the capacity and intention to preserve it for future generations? There is not strong evidence that the Nigerian govern.’

There is not strong evidence that the Nigerian

government have the capacity to preserve the Benin Bronzes for future

generations. P. 51.

‘Stewards should consider where the object has the greatest educational benefit. The Benin Bronzes have the greatest educational benefit in the British Museum, where they are contextualised by a universal collection.’

The Horniman Museum, London, the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford, and The Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge are all also excellent,

well curated museums. It is difficult to ascertain the educational benefit of the proposed Edo Museum of West African Art until it is built; however, it could potentially have high educational benefit. The fact that the Bronzes, items of global historical significance, p in places – including in Nigeria – provides greater educational benefit than if they were all in a single country.’ P. 52.

Stewards should conduct a full consultation of their visitors and the wider public before returning an object. If the first seven principles indicated significant benefit could be derived from returning the the Benin Bronzes, then stewards should conduct a full consultation before moving forward with the move. On the balance of these principles, this is not necessary.’P.53

‘Verdict: The Benin Bronzes The case for accepting the claim for restitution of the Benin Bronzes is weak. The risk the bronzes might be damaged or confined to a private collection is too great to justify return, particularly given it is not possible to accurately determine the location or security of many of the Bronzes believed to already reside in Nigeria. The question of claims and cultural links is also complex and does not provide a strong case for restitution. While the Bronzes were taken from Nigeria as spoils of war by Britain, some of the Bronzes themselves were created in Benin with brass obtained by selling the people of Benin into chattel slavery. The descendants of those enslaved people, many of whom now reside in the UK and the United States, also have a strong cultural link to the Bronzes.’ Pp. 52-53.

‘Except for in very rare cases of recent theft – such as Nazi Spoliation, stewards should not pay for the return of an artefact. The claimant must shoulder the costs of transportation. This demonstrates a claimant’s ability to safeguard an artefact and ensures that the UK Museum is not disadvantaged by a high cost which doesn’t contribute to their educational purpose.’ P.56.

‘Good curation takes time. Provenance research is a complex and long process. Stewards should never respond to social pressure to reach a decision fast. Even after a final decision is made regarding restitution or retention, they should take time to properly review any impending curatorial decisions.’ P.57

‘Our eight Principles for Restitution offer an impartial heuristic through which those in museums can assess such claims, taking into account not only their legal responsibilities, but their moral responsibilities as stewards of humanity’s shared history.’ P. 58.

IMAGES

The unforgettable Melina Mercouri, Greek Culture Minister (1981-89,1993-94) speaking to Boris Johnson in 1986 before her Oxford Union speech. Johnson was then passionately in fav our of returning the Parthenon Marbles to Athens.

‘You must understand what the Parthenon Marbles mean to us. They are our pride. They are our sacrifices. They are our noblest symbol of excellence. They are a tribute to the democratic philosophy. They are our aspirations and our name . They are the essence of Greekness. Melina’s Speech at the Oxford

Union. https://www.parthenon.newmentor.net/speech.htm

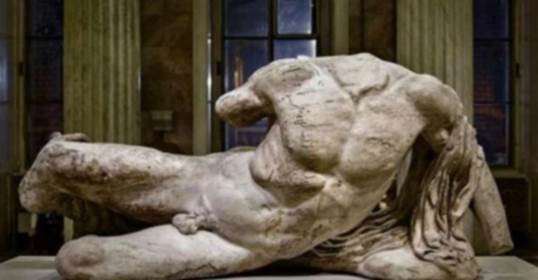

Parthenon Marbles, Athens, Greece, now in British Museum, London.

.

.

Headless statue of the Greek river god Ilissos, Athens, Greece which the British Museum had sent in 2014 on loan to the Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. The British Museum had confidence in Russia than in Greece to which the museum refused to loan the Parthenon Marbles.

Members of the notorious Punitive Expedition of 1897 proudly displaying some of their loot.

, from whose palace the Benin artefacts were looted, with guards on board ship on his way to exile in Calabar in 1897.

The ivory hip-mask depicting the image of the famous Queen-mother Idia, Benin, looted in 1897, now in the British Museum which the British Government refused to lend to Nigeria for the Pan-African Festival Festac77. In 2025 British Museum Director confirmed it will not be restituted.

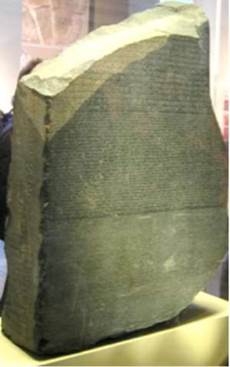

Rosetta Stone, Egypt, now in British Museum, London, United Kingdom.

Ethiopian church silver censer, looted at Maqdala, Ethiopia, in the 1868 invasion, now in British Museum, London, United Kingdom.

Processional cross, engraved with a representation of the Twelve Apostles, Maqdala, bought by Richard Rivington Holmes, a British Museum official who went with the invading British Army.

Porcelain vases, China, now in British Museum, Percival David Collection, London, United Kingdom.

Cloisonné jar, Ming Dynasty China, now in the British Museum, London United Kingdom.

Amaravati Marbles,India,now in the British Museum, London.

Shiva, Hindu God, India, now in British Museum, London.

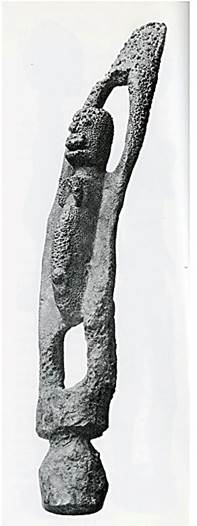

Wooden female figure with cylindrical torso excavated by Marcel Griaule in 1935, A female ancestor or Nommo. Mali, now in British Museum, London.

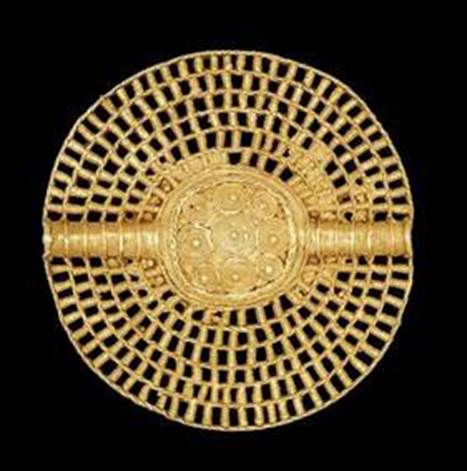

Asante ceremonial gold hat won by courtiers. Stolen in 1874 by British soldiers, ‘loaned’ in 2022 to Asante by British Museum that in 2025 declared the museum will not restitute the cap. British Museum and Victoria and Albert Museum Loan Looted Asante Artefacts to Asante

/Ghana: Where is the morality?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/1295729/british-museum-and-victoria-and-albert- museum-loan.html

Soulwasher’s badge, Akrafokunumu, one of the looted Asante objects ‘loaned’ to Asante by the British Museum.

We should not forget that hundreds of looted Asante artefacts are still in other British

institutions such as the Victoria and Albert Museum which’ loaned’ a few gold items to Asante. The Wallace Collection, London, is silent on restitution but on its own admission, holds an Asante trophy head,1.36kg,’one of the largest historic gold objects from Africa outside Egypt’’. ‘The head is among the most important and famous works of Asante art’ https://www.wallacecollection.org/explore/collection/search-the-collection/trophy-head/

How can directors and curators, conscious that they are withholding the finest and best art of the Asante people, refuse to return such objects?

Asante trophy head looted by the British in the 1874 invasion of Kumase, Ghana, now in Wallace Collection, London.