The global maritime industry, which transports over 80% of the world’s traded goods by volume (UNCTAD, 2023), is governed by a patchwork of legal jurisdictions. One of the most controversial yet entrenched practices in this sector is the use of Flags of Convenience (FOC)—a system that allows ships to be registered in a country other than that of the vessel’s owners. Although often framed as a commercial decision, the proliferation of FOCs raises complex issues related to regulatory evasion, labour exploitation, and maritime safety. The origins of the FOC system date back to the early 20th century. In the aftermath of World War I and during the Prohibition era in the United States, American shipowners began registering vessels under the Panamanian flag to legally serve alcohol and avoid restrictive U.S. regulations (Alderton & Winchester, 2002).

Panama formalised its open registry in 1917, establishing the blueprint for what would later become a global practice. Following Panama’s model, Liberia launched its registry in 1948 with support from American business interests, creating a competitive system that incentivised shipowners to seek jurisdictions with minimal oversight. Over the decades, other nations, particularly small or developing states, entered the open registry market to generate revenue by offering flagging services with limited regulatory burdens. A flag of convenience refers to the practice of registering a merchant vessel in a country with no substantive connection to the shipowner, primarily to benefit from favourable legal, regulatory, and fiscal regimes (BIMCO, 2023). Unlike traditional flag states, which often impose rigorous safety and labour standards, FOC states typically: Allow foreign ownership with no local presence; Have minimal labour law enforcement; Provide reduced tax obligations or tax exemptions; Offer quick and low-cost registration services and Exercise limited control over vessel operations (UNCTAD, 2023; IMO, 2021).

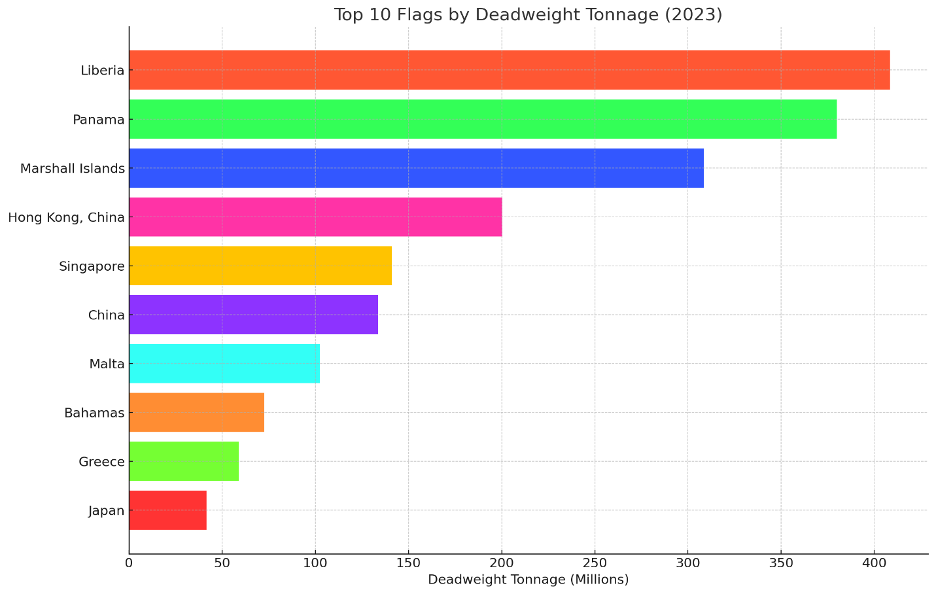

These features make open registries attractive for global shipowners seeking flexibility and cost efficiency. However, they also undermine the principle of the “genuine link” between a vessel and its flag state, as stipulated in Article 91 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). As of 2023, Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands collectively account for over 45% of the global merchant fleet by deadweight tonnage (UNCTAD, 2023).

The following statistics highlight their dominance:

Panama: 8,274 vessels, representing 16.3% of global tonnage;

Liberia: 5,133 vessels, 14.7% of global tonnage;

Marshall Islands: 4,891 vessels, 14.5% of global tonnage.

This concentration reflects a clear preference within the shipping industry for registries that offer legal insulation, low tax obligations, and minimal compliance burdens. Shipping companies often justify the use of FOC registries on the grounds of economic efficiency. Operating under an open registry can reduce operating costs by up to 30% due to lower wage bills, reduced inspection obligations, and streamlined compliance requirements (Clarkson Research, 2023). Additionally, FOCs provide a shield against legal liabilities and political risks by separating the vessel’s legal identity from its beneficial owners. This structure is particularly beneficial in an industry where multi-national crew compositions, offshore financing, and flag-hopping practices are commonplace (ITF, 2022). However, this same business rationale also enables regulatory arbitrage, where shipowners selectively choose jurisdictions that offer the least stringent oversight, often at the expense of safety, environmental protection, and labor rights.

1. Global Leaders in Flag Registries

The global dominance of open registries is shaped by a few key players—Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands, whose collective control of nearly half of the world’s merchant fleet has positioned them at the centre of debates on maritime sovereignty, safety, and labour rights. These registries have built their market share by offering attractive terms to shipowners while maintaining limited regulatory obligations. Understanding their structure and appeal provides critical context for analysing the systemic issues within the Flag of Convenience (FOC) regime.

1.1 Panama – The Original and Largest Open Registry

Panama’s maritime registry, officially established in 1917, is the oldest and largest open registry in the world. As of 2023, it boasts over 8,000 vessels, representing more than 16% of global merchant shipping tonnage (Panama Maritime Authority [AMP], 2022; UNCTAD, 2023). The registry is administered by the AMP but operated globally through a decentralised network of private agencies in key maritime hubs like Piraeus, Singapore, and Dubai.

The Panamanian model is highly commercialised and offers:

– Low fees and taxes, including no corporate income tax on international shipping income;

– Simplified online registration processes;

– Minimal labour oversight, making it attractive for shipowners seeking to avoid the costs associated with International Labour Organisation (ILO) enforcement.

Despite being a signatory to major IMO and ILO conventions, enforcement remains weak. According to the Paris MoU (2023), Panamanian-flagged vessels frequently appear on watchlists for safety and labour violations, with above-average detention rates.

1.2 Liberia – A U.S.-Backed Flag with Flexible Laws

Liberia established its registry in 1948 with direct backing from American business and geopolitical interests, originally operated by a New York-based law firm. Today, the Liberian Registry remains privately operated by LISCR (Liberian International Ship and Corporate Registry) and is legally headquartered in the United States, though nominally linked to Liberia.

With over 5,100 registered vessels and nearly 15% of the world fleet by tonnage, Liberia’s appeal lies in:

– Quick and cost-efficient flagging with electronic processing;

– Access to U.S. political and defence protections (beneficial for American interests);

– Flexible labour policies that enable the employment of low-wage multinational crews.

Despite its robust image and slightly better compliance record than Panama, Liberia has faced criticism over poor accident investigations and a lack of accountability in high-profile maritime incidents (ITF, 2022; Alderton & Winchester, 2002).

1.3 Marshall Islands – A Rising Maritime Powerhouse

The Marshall Islands registry has emerged as the third-largest open registry, with over 4,800 vessels and a significant share of LNG carriers and oil tankers (Clarkson Research, 2023). Administered by International Registries Inc. (IRI) and headquartered in Reston, Virginia, USA, the Marshall Islands operates in a quasi-private capacity similar to Liberia.

This registry has grown rapidly due to its:

– Strong customer service model;

– Broad acceptance by major insurers and port states;

– Stable regulatory environment with less public scrutiny than Panama or Liberia.

However, critics argue that its rapid expansion has not been matched by adequate increases in oversight capacity, creating potential gaps in safety and labour protections (Paris MoU, 2023).

1.4 Traditional Registries vs. Open Registries

In contrast, traditional maritime nations such as the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States maintain stricter conditions for vessel registration. These often include:

– Requirements for domestic ownership or management;

– Full compliance with national labour, tax, and safety laws;

– Regular inspections and crewing standards.

Consequently, their fleets have diminished as shipowners seek out FOCs for operational flexibility and cost savings. The U.S. Merchant Marine, for example, has declined to fewer than 200 internationally trading vessels (U.S. Maritime Administration, 2023), down from thousands in the mid-20th century. Figure 1 below illustrates the top 10 flags by deadweight tonnage in 2023.

Figure 1: 10 Flags by Deadweight Tonnage in 2023

Source: UNCTAD (2023), Clarkson Research (2023)

2. Regulatory Implications of FOC Systems

At the heart of the Flags of Convenience (FOC) controversy lies the critical issue of regulatory effectiveness—or more pointedly, the lack thereof. Open registries, while economically advantageous for shipowners, present significant governance challenges, primarily due to their weak or inconsistent enforcement mechanisms. This section delves into the structural gaps and compliance challenges that characterise FOC states, highlighting their implications for maritime safety, environmental standards, and international legal accountability.

2.1 Weak Flag State Control (FSC)

Under international maritime law, notably the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982), a flag state is legally responsible for enforcing safety, environmental, and labour standards aboard its vessels. In practice, however, open registries frequently fail in this obligation. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) Member State Audit Scheme (IMSAS), launched through Resolution A.1070, underscores significant inconsistencies in how FOC states meet their regulatory responsibilities (IMO, 2021).

The audits have repeatedly noted that states with open registries often:

– Lack sufficient resources to inspect and regulate their large fleets effectively;

– Outsource inspection and certification to private classification societies with varying standards and reliability;

– Have inadequate processes for dealing with reported violations (IMO, 2021).

This regulatory void makes vessels flying FOC flags susceptible to substandard operating practices, which significantly compromise maritime safety and environmental integrity.

2.2 Jurisdictional Fragmentation and Accountability

FOC systems further exacerbate the regulatory challenge by creating complex, multi-layered ownership structures. Vessels under open registries are frequently owned by shell corporations in jurisdictions distinct from both their operational management and their flag states. This corporate fragmentation complicates accountability, making it difficult for authorities to establish responsibility or enforce penalties for maritime incidents, violations, and labour abuses (Alderton & Winchester, 2002). Investigations into maritime accidents often reveal convoluted ownership networks involving offshore financial centres, limiting transparency and hindering regulatory action. This fragmentation effectively insulates beneficial owners from liability, significantly undermining international maritime governance.

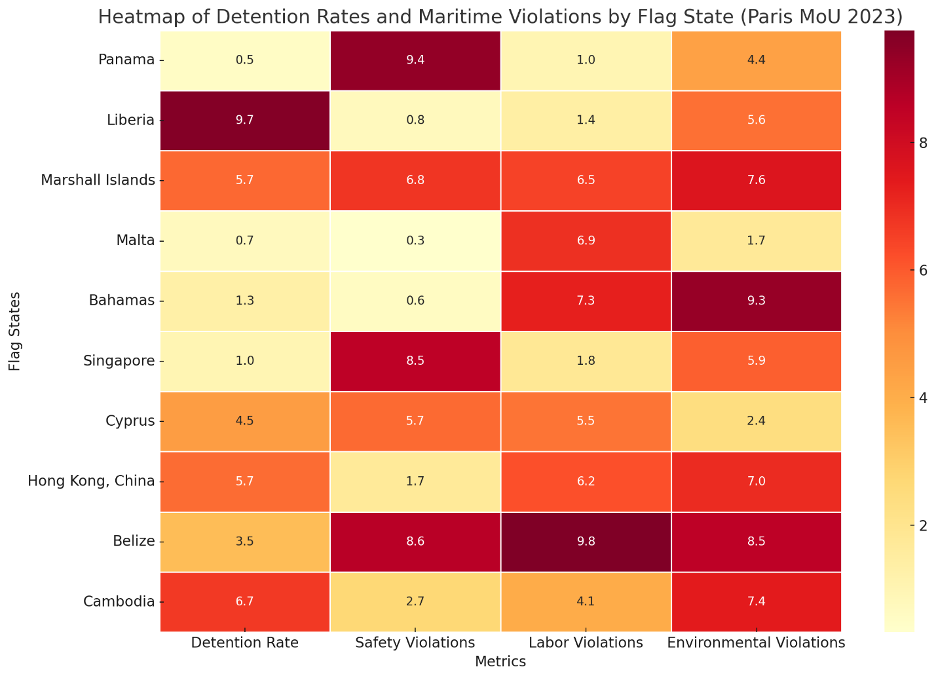

2.3 Substandard Vessels and Increased Maritime Risks

Empirical evidence from Port State Control (PSC) inspections consistently highlights increased regulatory non-compliance among ships registered in FOC jurisdictions. For instance, annual reports published by the Paris Memorandum of Understanding (Paris MoU) indicate higher detention rates for vessels flagged by open registries compared to traditional flag states. In 2022, Panama’s detention rate was approximately 6.3%, significantly above that of the United Kingdom (1.1%) and Marshall Islands (2.4%) (Paris MoU, 2023). The “Black List” and “Grey List” published annually by Paris MoU frequently include flags of convenience such as Sierra Leone, Togo, and Belize—each exhibiting persistent deficiencies in safety, environmental compliance, and crew welfare (Paris MoU, 2023). Such statistical patterns confirm that FOC registration correlates with lower compliance and higher operational risk, directly threatening vessel and crew safety and heightening environmental hazards.

2.4 Weak Enforcement of International Safety and Environmental Regulations

Compliance with core international maritime treaties—including the Safety of Life at Sea Convention (SOLAS), International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), and Maritime Labour Convention (MLC)—depends primarily on active enforcement by flag states. However, open registries typically adopt minimalist regulatory approaches, conducting infrequent or cursory inspections and relying heavily on delegation to third-party private classification societies. This weak enforcement regime significantly dilutes international standards. Environmental regulations, such as restrictions on emissions, oil spills, ballast water discharge, and hazardous waste management, often remain inadequately enforced on FOC vessels, posing severe environmental risks, particularly to fragile marine ecosystems and coastal communities (ITF, 2022; UNCTAD, 2023).

2.5 Illustrative Example: Panama’s Regulatory Challenges

Panama’s extensive fleet provides a telling example. With over 8,000 vessels, Panama relies almost exclusively on private classification societies for compliance inspections. However, the wide variance in standards and transparency among these societies often results in inconsistent inspections and certification practices. A 2023 IMO audit highlighted Panama’s insufficient oversight of classification societies, limited follow-up on deficiencies, and slow enforcement actions, reinforcing international concerns about regulatory integrity under Panama’s flag (IMO, 2023). Below is the heatmap of detention rates and maritime violations by flag state in 2022.

Figure 2: Heatmap of Detention Rates and Maritime Violations by Flag State in 2022

Source: Paris MoU 2023 data

3 Labor Standards and Human Rights under FOCs

The global maritime workforce comprises approximately 1.9 million seafarers who operate in conditions significantly influenced by their vessel’s flag state (International Labour Organisation [ILO], 2023). Flags of Convenience (FOC), while economically advantageous to shipowners, profoundly impact seafarer welfare, frequently leading to diminished labour protections, substandard working conditions, and systemic human rights abuses. Despite the widespread ratification of key international conventions, notably the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC 2006), enforcement remains inconsistent, largely due to the regulatory limitations inherent in open registry states.

3.1 Disparities in Seafarer Working Conditions

The most direct consequence of FOC registration is the substantial variation in working conditions, wages, and contractual security experienced by maritime crews. Vessels flagged under open registries typically employ multinational crews, often recruited from developing countries—primarily the Philippines, Indonesia, India, Ukraine, and Ghana—at significantly lower wages compared to those aboard traditional registry vessels (ITF, 2022). Wage disparities can exceed 50–70%, reinforcing a global labor market hierarchy exacerbated by the lax enforcement capabilities of FOC states. Furthermore, the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) reports recurring cases of non-payment or delayed wages, fraudulent employment contracts, and excessively prolonged periods at sea without adequate rest or leave (ITF, 2022). While MLC 2006 explicitly addresses these conditions, enforcement by FOC states frequently falls short, leaving seafarers vulnerable and largely without recourse.

3.2 Undermining of ILO Maritime Labour Convention (MLC 2006)

The MLC 2006, often described as the “seafarers’ bill of rights,” was designed to set international minimum standards for employment conditions aboard ships. Although widely ratified, including by major FOC states such as Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands, compliance monitoring is heavily dependent on effective flag state enforcement. Unfortunately, evidence suggests significant enforcement gaps persist under these flags. Data from port state control inspections by the Paris and Tokyo MoUs consistently identify MLC-related violations among vessels flying convenience flags. Common deficiencies include inadequate crew accommodations, insufficient rest hours, poor food and water quality, inadequate medical care, and failure to provide employment contracts in understandable languages (Paris MoU, 2023). Despite their ratification commitments, FOC states often lack the institutional capacity or political will to pursue corrective actions effectively.

3.3 Exploitation through Multi-national Crewing Practices

A primary economic incentive behind FOCs is the opportunity to recruit seafarers globally, taking advantage of regional wage disparities. This multinational crewing model, while cost-effective for shipowners, often facilitates exploitative practices. Crews hired through global crewing agencies frequently face unclear jurisdictional oversight, complicating enforcement of labor rights and exacerbating vulnerability to abuse (Alderton & Winchester, 2002). For instance, the ITF (2022) documented numerous cases where crews were systematically subjected to unsafe working conditions, excessive working hours, and inadequate training or protective equipment. In many instances, FOC states offer minimal intervention, leaving crew members without legal protection or practical remedies.

3.4 High-Profile Abuse Cases and Limited Accountability

The limited accountability under FOCs is vividly illustrated by numerous high-profile cases of crew abandonment and abuse. For example, in 2021, the bulk carrier MT Iba, registered under Sierra Leone’s open registry, was abandoned off the coast of the United Arab Emirates with its crew stranded aboard without pay or adequate supplies for months. Despite international attention, flag-state authorities provided little intervention, leaving humanitarian organisations and port state officials to resolve the crisis (ITF, 2021). Such incidents underline the systemic weaknesses of FOCs in protecting basic human rights, highlighting how jurisdictional fragmentation and weak enforcement mechanisms often leave seafarers in precarious conditions.

3.5 Impact on Global Maritime Labour Standards

The proliferation of FOC registries has exerted downward pressure on global maritime labour standards, creating a competitive “race to the bottom” among flag states. Traditional registries seeking to retain their fleets increasingly face pressures to relax labour regulations, thereby undermining international efforts toward improved seafarer welfare. The resulting global disparity in labour standards poses significant ethical and humanitarian concerns, directly challenging international governance structures intended to protect maritime labour rights.

4 Maritime Safety and Environmental Oversight

The rapid expansion of Flags of Convenience (FOC) registries has been associated with persistent challenges in maritime safety enforcement and environmental protection. Despite international frameworks designed to safeguard shipping operations, most notably the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) and the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), vessels operating under open registries frequently evade rigorous compliance monitoring. This systemic weakness has resulted in heightened risks of maritime incidents, environmental disasters, and compromised global shipping safety standards.

4.1 Correlation between FOCs and Major Maritime Disasters

Historical analysis reveals a troubling correlation between FOC-flagged vessels and catastrophic maritime incidents. Prominent examples include:

MV Erika (1999): A Maltese-flagged tanker broke apart off the French coast, causing extensive environmental damage through massive oil spills. Investigations highlighted lax inspection procedures and inadequate oversight by the flag state (European Maritime Safety Agency [EMSA], 2000).

Prestige (2002): Registered under the Bahamas flag, this tanker spilled over 60,000 tonnes of heavy fuel oil off the coast of Spain. Subsequent investigations found critical deficiencies in vessel maintenance, crew training, and inadequate enforcement of regulatory standards by the flag state (EMSA, 2003).

These incidents prompted stricter regional regulations within the European Union, but global enforcement disparities continue due to fragmented regulatory control by many open registry states.

4.2 Inadequate Safety Inspections and Port State Control (PSC)

Port State Control inspections, designed as a secondary check on maritime compliance, frequently identify disproportionately high levels of safety and environmental deficiencies among FOC vessels. According to the Paris MoU (2023), vessels flagged by states such as Panama, Belize, Sierra Leone, and Togo exhibit significantly higher detention rates due to safety violations compared to traditional flags like the United Kingdom, Norway, and Japan. For instance, Panama, despite its dominance as a global maritime registry, continues to exhibit above-average detention rates. In 2022, Panama’s vessel detention rate was 6.3%, contrasted with the UK’s significantly lower detention rate of approximately 1.1% (Paris MoU, 2023). These statistics underscore systemic oversight weaknesses within open registries.

4.3 Environmental Governance Deficiencies

The enforcement of global environmental regulations under FOCs remains particularly problematic. While major open registry states are signatories to MARPOL, implementation and monitoring remain inconsistent. Issues such as illegal oil discharges, non-compliance with ballast water management systems, improper disposal of hazardous waste, and violations of sulfur emission caps are notably higher among FOC-flagged vessels (ITF, 2022; IMO, 2021). The “regulatory outsourcing” common under FOC systems, where inspection and certification responsibilities are delegated to private classification societies, creates significant disparities in environmental compliance. These societies vary widely in stringency and transparency, leading to uneven environmental standards enforcement and increased risk of pollution incidents.

4.4 Case Study: Panama vs. UK Flag – Safety and Environmental Compliance

Comparative analyses provide compelling evidence of how open registries impact safety and environmental compliance. A detailed comparison of Panama and the United Kingdom, two major maritime registries operating under contrasting regulatory regimes, highlights critical distinctions:

This stark contrast illustrates the profound influence of registry type on operational safety, environmental stewardship, and vessel condition.

4.5 IMO Guidelines and Regional MoU Enforcement

The International Maritime Organisation (IMO), recognising the limitations of relying solely on flag state enforcement, promotes rigorous Port State Control (PSC) as a critical oversight mechanism through regional agreements such as the Paris, Tokyo, and Abuja MoUs. However, enforcement remains uneven globally. Notably, PSC authorities in regions with limited resources (e.g., West and Central Africa under the Abuja MoU) struggle to implement rigorous inspection regimes, enabling FOC vessels with deficient safety standards to operate largely unchecked in these regions (IMO, 2023). Enhanced global cooperation, resource allocation, and training for PSC inspectors—particularly in developing regions—are urgently needed to address these critical safety and environmental oversight gaps.

5. Legal and Institutional Critiques

Flags of Convenience (FOC) represent not only an economic and operational phenomenon but also a significant challenge to international maritime law and governance. The persistent failure of open registries to enforce fundamental legal obligations underlines weaknesses within international maritime conventions and institutional frameworks. This section critically examines legal limitations, institutional inadequacies, and key critiques by international bodies aimed at addressing systemic gaps associated with FOCs.

5.1UNCLOS and the “Genuine Link” Debate

Central to legal critiques of FOCs is the concept of the “genuine link,” as articulated under Article 91 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS, 1982). This provision stipulates that a genuine economic or operational connection must exist between a vessel and its flag state to ensure effective jurisdictional control. However, despite its clear wording, this requirement remains largely symbolic, with limited practical enforcement (Alderton & Winchester, 2002; ITF, 2022). Flag states employing open registries systematically ignore or circumvent the genuine link criterion, allowing shipowners to register vessels without substantial economic presence or regulatory oversight. The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) has yet to decisively address this enforcement gap, leaving open registries to continue operating under minimal accountability, thereby undermining the legitimacy of international maritime law.

5.2 IMO and ILO Harmonisation Efforts: Limitations and Challenges

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Labour Organisation (ILO) have made extensive efforts to harmonize regulatory standards and enforcement through instruments such as the Safety of Life at Sea Convention (SOLAS), the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC 2006), and the Prevention of Pollution from Ships Convention (MARPOL). However, the effectiveness of these conventions critically depends on individual flag state enforcement. Institutional assessments, such as those conducted through the IMO Member State Audit Scheme (IMSAS), reveal substantial implementation deficiencies among major open registries, including inadequate inspections, poor accident investigation processes, and delayed enforcement actions (IMO, 2023). The reliance of IMO and ILO on flag states’ voluntary compliance underscores a fundamental institutional limitation, severely curtailing the effectiveness of international maritime governance.

5.3 UNCTAD and ITF Positions on FOC Abuses

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) have persistently criticised FOCs for their role in fragmenting maritime governance and facilitating systemic labour abuses. UNCTAD, in its 2023 Review of Maritime Transport, emphasises the urgent need for stricter international oversight mechanisms, citing that regulatory loopholes under FOCs directly compromise global maritime safety, environmental protection, and fair labour standards (UNCTAD, 2023). Similarly, the ITF’s long-running Flag of Convenience Campaign explicitly calls for international regulatory reform, increased port state control vigilance, and the development of mechanisms to enforce the genuine link principle. The ITF highlights the human rights implications, particularly crew abandonment and abuse cases frequently reported aboard vessels flying convenience flags (ITF, 2022).

5.4 U.S. Congressional Hearings: FOC and Maritime Tax Evasion

In recent years, the United States Congress has intensified scrutiny on maritime tax evasion and related abuses facilitated by open registries. A 2021 hearing by the U.S. House of Representatives Maritime Subcommittee highlighted concerns surrounding FOCs’ role in facilitating tax avoidance, money laundering, sanctions evasion, and even human trafficking. Testimony from maritime law experts revealed systemic weaknesses in transparency and accountability within major open registries, especially Panama, Liberia, and the Marshall Islands (U.S. House Maritime Subcommittee, 2021). Congressional discourse has called for stricter international regulatory frameworks, enhanced disclosure requirements, and intensified coordination among international bodies such as the IMO, ILO, and Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to tackle these systemic risks effectively.

5.5 Institutional Limitations and the Need for Reform

Institutional critiques have converged around a common consensus that current international regulatory mechanisms are insufficient to effectively manage or mitigate the risks associated with FOCs. The IMO and ILO, despite having established extensive regulatory conventions, possessed limited direct enforcement power and relied heavily on voluntary compliance by flag states, many of whom lack the will or capacity to implement rigorous standards effectively. The decentralised and fragmented nature of maritime governance under FOCs further complicates efforts to strengthen institutional oversight. The delegation of regulatory enforcement to private classification societies, often criticised for conflicts of interest, exacerbates compliance and accountability challenges (IMO, 2021).

6. Strategic Recommendations for Reform

Addressing the systemic challenges posed by Flags of Convenience (FOC) requires targeted, coordinated, and enforceable international policy responses. Given the persistent legal, safety, environmental, and labour violations associated with open registries, it is imperative to enhance transparency, accountability, and compliance within the global maritime governance framework. This section outlines practical and achievable strategic recommendations, drawing on best practices and institutional insights from international maritime bodies, labour organisations, and leading national regulatory frameworks.

6.1 Strengthening Port State Control (PSC) Enforcement

Effective reform begins with enhanced Port State Control mechanisms. Given the weaknesses inherent in flag state oversight, PSC serves as a critical layer of international enforcement. Recommendations include:

– Prioritised Inspections: Implement targeted PSC inspections prioritising vessels flagged by states consistently identified on “Black Lists” or “Grey Lists” under the Paris and Tokyo MoUs. Enhanced inspection frequency should directly correlate with historical compliance records and risk profiles (Paris MoU, 2023).

– International Inspection Database: Establish a global database managed by the IMO, accessible to all PSC authorities, documenting vessel histories, prior detentions, crew complaints, and unresolved deficiencies. Transparency in this system would enhance international enforcement consistency.

6.2 Imposing Effective “Genuine Link” Compliance Checks

The “genuine link” principle stipulated under Article 91 of UNCLOS must transition from symbolic policy to enforceable international law:

– Mandatory IMO-ILO Certification: Require explicit verification of economic or operational linkage between vessel ownership and flag state registration. IMO and ILO should jointly issue compliance certifications based on transparent criteria, enforceable through PSC and port entry restrictions for non-compliant vessels.

Legal Accountability Framework: Encourage the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) to develop jurisprudence clarifying “genuine link” obligations, thereby providing a clear legal precedent for enhanced flag state accountability.

6.3 Incentivising Responsible Ship Registries (“Green Flag” Programs)

To balance punitive enforcement with positive reinforcement, international maritime bodies should introduce incentivised compliance systems:

– “Green Flag” Registry Programs: Create international rating systems evaluating registries based on environmental standards, labour compliance, and safety enforcement. Registries achieving high compliance ratings would benefit from lower PSC inspection frequencies, reduced insurance premiums, and preferential market access.

– Tax and Port Fee Incentives: Port states should offer discounted harbour fees or preferential berthing to vessels flying flags from highly rated, responsible registries. Such market-driven incentives can effectively promote voluntary compliance among shipowners.

6.4 Enhancing Labour Standards Enforcement via Global Seafarers’ Registry

A significant step toward protecting seafarer rights under FOCs is establishing a Global Seafarers’ Registry, jointly administered by the ILO and ITF:

– Seafarer Employment Records: This centralised database would document crew employment contracts, wage payment compliance, working conditions, and grievances. Transparent, verifiable crew records accessible to PSC inspectors would empower enforcement of the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC 2006).

– Rapid Response Mechanisms: Establish protocols enabling swift intervention in crew abandonment or abuse cases, ensuring immediate humanitarian and legal support, irrespective of flag state responsiveness.

6.5 Increasing Transparency in Beneficial Ownership

Given the complex corporate structures behind FOC-registered vessels, increasing transparency in beneficial ownership is essential:

– Mandatory Beneficial Ownership Disclosure: IMO regulations should mandate that flag states publicly disclose vessel beneficial ownership details, making corporate accountability explicit and reducing regulatory evasion via anonymous shell companies.

– Integration with Financial Oversight: Strengthen cooperation between IMO, FATF, and national financial regulators to trace maritime-related illicit financial flows, tax evasion, and sanction violations.

6.6 Capacity-Building for Developing Country Port States

Enhanced international capacity-building programs are necessary to address regional enforcement disparities, particularly within African and other developing maritime regions:

– IMO-ILO Joint Training Programs: Establish comprehensive training and certification programs for PSC inspectors in developing countries, focusing on identifying labor abuses, environmental violations, and safety risks aboard FOC vessels.

– Funding and Technical Assistance: Provide targeted international financial and technical assistance to strengthen maritime regulatory infrastructures in regions with historically weak enforcement capacity (e.g., Abuja MoU region).

6.7 Strengthened International Maritime Legal Frameworks

To effectively reform the FOC system, international maritime conventions require more robust enforcement mechanisms:

– Enhanced IMO and ILO Enforcement Powers: Grant greater investigatory and sanctioning authority to international maritime bodies to directly address persistent non-compliance by flag states.

– Binding International Arbitration: Promote binding arbitration mechanisms for resolving disputes related to flag-state compliance, thereby ensuring accountability beyond voluntary measures.

6.8 Leveraging Technology for Compliance Monitoring

Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), satellite monitoring, blockchain-based crew and vessel registries, and real-time environmental tracking should be integrated into maritime governance systems:

– Automated Compliance Systems: Implement AI-driven vessel tracking and automated compliance alert systems, allowing immediate identification and intervention in cases of illegal discharges, route deviations, and crew distress signals.

– Blockchain-Based Certification: Introduce blockchain-based digital compliance certifications for seafarer qualifications, vessel inspections, and environmental reporting, ensuring transparency, immutability, and traceability of compliance records.

7 Implications for African Port Development

Africa, home to a growing share of global maritime traffic, faces unique challenges and opportunities due to the widespread use of Flags of Convenience (FOCs). For African coastal states—including Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and others—improving maritime governance, enhancing port state control (PSC) effectiveness, and potentially developing transparent national registries presents an opportunity to significantly influence regional maritime safety, labour standards, and environmental compliance. This section explores strategic actions African nations can take to mitigate the negative effects of FOCs and build credible maritime governance frameworks aligned with continental policy goals.

7.1 Strengthening Port State Control Enforcement in African Ports

African states are part of regional PSC agreements, including the Abuja MoU (West and Central Africa) and the Indian Ocean MoU. However, PSC enforcement remains inconsistent, reflecting capacity constraints and inadequate resources. Strategic recommendations for enhancing PSC effectiveness in Africa include:

– Capacity-Building Initiatives:

Develop comprehensive training programs in collaboration with IMO, ILO, and experienced maritime states to enhance inspection capabilities of PSC officers in major African ports (e.g., Tema, Lagos, Mombasa).

– Resource and Infrastructure Investment:

Allocate strategic funding, supported by international partnerships (World Bank, African Development Bank), to modernise inspection facilities, technology, and administrative infrastructure within African port authorities.

– Regional Coordination:

Strengthen cross-border PSC coordination through increased data sharing, joint inspection programs, and harmonisation of regional maritime compliance standards under regional PSC MoUs.

7.2 Opportunities to Develop Credible National Ship Registries

African nations have significant potential to develop competitive, credible national maritime registries based on transparency, strong regulatory standards, and ethical governance. Countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and South Africa could leverage their emerging maritime capabilities and strategic locations to offer attractive yet responsible flagging alternatives to global shipowners. Policy recommendations for achieving this include:

– Establishing Transparent Registries:

Develop clear and transparent registration criteria, robust compliance frameworks, and high operational standards aligned with international maritime conventions (SOLAS, MARPOL, MLC 2006).

– Investment in Regulatory Oversight:

Invest in national maritime regulatory bodies with adequate resources, skilled personnel, and advanced technological platforms for effective vessel monitoring, inspection, and enforcement of international compliance.

– International Benchmarking:

Adopt international best practices from reputable national registries (UK, Norway, Japan) and develop strategic alliances with respected maritime administrations to enhance credibility and global acceptance.

7.3 Alignment with AU’s Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS 2050)

The African Union’s Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS 2050) emphasises sustainable maritime development, enhanced maritime security, and protection of marine environments. Addressing the challenges posed by FOCs directly supports these strategic goals. Specifically, policy implications for alignment with AIMS 2050 include:

– Enhanced Maritime Security Frameworks:

Strengthen maritime surveillance and enforcement measures targeting FOC vessels involved in illegal fishing, illicit trade, or environmental violations, using regional cooperation frameworks to enhance maritime domain awareness.

– Sustainable Environmental Stewardship:

Integrate stringent environmental compliance measures within PSC inspection processes, with a focus on preventing illegal waste dumping, oil discharges, ballast water violations, and emissions control breaches, to protect African coastal and marine ecosystems.

– Labour Rights and Welfare:

Implement rigorous enforcement of ILO’s Maritime Labour Convention within PSC activities at African ports, actively addressing seafarer exploitation, abandonment, and abuse prevalent among FOC vessels operating in African waters.

7.4 Leveraging Regional Maritime Cooperation for Improved Compliance

Regional integration initiatives, such as ECOWAS, SADC, and EAC, provide platforms for coordinated maritime compliance efforts. Recommendations for leveraging regional maritime cooperation include:

– Regional Maritime Compliance Database:

Develop regional data-sharing platforms accessible to all member states, tracking vessel compliance history, crew welfare issues, environmental violations, and ownership transparency to enable targeted PSC inspections.

– Joint Inspection Programs:

Initiate joint regional PSC inspection exercises, sharing resources, expertise, and enforcement capabilities to collectively improve maritime safety, labour standards, and environmental compliance.

– Regional Legal Harmonisation:

Harmonise regional maritime legislation to effectively enforce international conventions and standards uniformly, ensuring that FOC vessels do not exploit regulatory gaps within the region.

7.5 Strategic Policy Recommendations for Immediate Implementation

For rapid improvements, African coastal states can implement the following actionable policy recommendations:

– Immediate Investment in PSC Training:

Short-term, intensive training programs conducted in collaboration with IMO, targeting critical African ports, to immediately strengthen inspection quality and frequency.

– Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs):

Develop PPP models to attract investment for modernising port facilities, inspection technologies, and maritime surveillance infrastructure critical to enhanced compliance monitoring.

– Engagement with International Bodies:

Active participation in IMO and ILO committees to advocate for enhanced global regulatory frameworks addressing FOCs, ensuring Africa’s maritime governance priorities are internationally recognised and supported.

Conclusion

Flags of Convenience (FOC) have transformed global maritime governance, profoundly influencing international trade dynamics, labour practices, safety enforcement, and environmental protection. Initially embraced by the shipping industry as a commercial advantage, open registries have become emblematic of broader governance challenges: fragmented jurisdictions, diminished regulatory accountability, systemic labour exploitation, and environmental harm. Addressing these issues demands a fundamental reevaluation and restructuring of global maritime sovereignty and responsibility frameworks. The concept of maritime sovereignty inherently involves robust state accountability for vessels bearing national flags. Yet, the proliferation of open registries has diluted this principle, effectively decoupling maritime responsibility from vessel nationality. Restoring credibility requires stringent enforcement of international maritime conventions—SOLAS, MARPOL, and MLC 2006—underpinned by practical implementation of the “genuine link” principle articulated in UNCLOS Article 91. Flag states must assume unequivocal regulatory responsibility, prioritising comprehensive enforcement, robust monitoring, and transparency in ownership and operational compliance.

Achieving this will necessitate significant reform in international maritime governance, creating enforceable standards supported by coordinated international action. A sustainable and equitable maritime future hinges on rebuilding legal accountability across jurisdictions. Maritime commerce, crucial to global economic interdependence, should no longer tolerate regulatory arbitrage or systemic abuses under FOCs. International institutions—IMO, ILO, ITLOS, and UNCTAD—must lead in developing enforceable legal frameworks capable of holding flag states and shipowners accountable for compliance violations.

– Legal accountability mechanisms must address:

– Transparent beneficial ownership disclosures;

– Robust environmental safeguards;

– Comprehensive labour rights protections;

– Strong safety and inspection regimes;

– Enhanced Port State Control capabilities worldwide.

Establishing clear international benchmarks and strengthening legal accountability will reinforce compliance, protect maritime labour, safeguard the marine environment, and restore integrity to global shipping operations.

For Africa, addressing FOC issues is not merely regulatory—it represents a strategic economic and governance opportunity. By strengthening port state controls, investing in credible national registries, and aligning maritime policy with continental strategies like the Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy (AIMS 2050), African coastal states can significantly reshape their maritime futures. This approach positions Africa as a leader in ethical and sustainable maritime governance, potentially attracting responsible global shipping companies seeking transparency and robust regulatory standards. The future of maritime governance will undoubtedly involve advanced technological solutions. Artificial Intelligence (AI), blockchain technologies, satellite monitoring, and automated compliance systems offer powerful tools for enhancing regulatory effectiveness, transparency, and real-time enforcement capabilities. Integrating these technologies into maritime regulatory frameworks can drastically improve oversight, quickly identify non-compliance, and efficiently protect human and environmental safety at sea.

The maritime industry’s evolution toward digitalisation and sustainability underscores the urgency for governments, institutions, and shipowners to adapt and commit to responsible maritime practices. Technological advancements offer the prospect of addressing long-standing regulatory gaps, potentially reshaping the very nature of maritime sovereignty and responsibility.

Ultimately, addressing the systemic issues presented by Flags of Convenience demands collective international action. Maritime sovereignty, historically viewed as a national prerogative, must evolve into a shared global responsibility. International maritime organisations, national governments, shipping companies, and civil society must work collaboratively to reform open registries, strengthen regulatory frameworks, and ensure accountability.

The maritime sector stands at a crossroads. One path perpetuates the systemic governance deficiencies inherent in FOCs, threatening environmental sustainability, human rights, and maritime safety. The alternative, more challenging yet necessary path, involves comprehensive reform—embracing robust, transparent, and ethical maritime governance that respects human rights, protects the environment, and ensures sustainable global commerce. The continued dominance of Flags of Convenience in global maritime trade underscores a critical governance failure that must be urgently addressed. By rethinking maritime sovereignty, enforcing international accountability, embracing technological innovation, and collectively committing to regulatory transparency, the international maritime community can achieve sustainable, responsible, and equitable maritime governance for future generations. This shift is not merely beneficial; it is essential. The credibility, sustainability, and ethical foundations of global maritime trade depend on decisive action today.

*******

Dr David King Boison, a maritime and port expert, AI Consultant and Senior Fellow CIMAG. He can be contacted via email at kingdavboison@gmail.com

DISCLAIMER: The Views, Comments, Opinions, Contributions and Statements made by Readers and Contributors on this platform do not necessarily represent the views or policy of Multimedia Group Limited.