South Africa’s century-long tradition of elite pact-making began with the 1910 Union, which forged white unity through excluding black South Africans from political life. In response, black elites—mostly Christianised African professionals and chiefs, collectively known as amazemtiti or ‘Black Englishmen’—formed the ANC in 1912, hoping to counter this settler compact through petitions and appeals to imperial justice.

“Tell England that we are not the barbarians they think we are.”—Sol Plaatje, 1914 formal protest letter to King George V against the Native Land Act, pleading for imperial intervention in the face of racial dispossession.

The 1926 Mines and Works Act reserved skilled jobs for whites, fuelling black elite frustration. This blatant economic ceiling, after failed imperial appeals, birthed the ANC’s militancy. It exposed the futility of moderate tactics against entrenched racial economic hierarchy.

The 1948 electoral victory of the Nationalist Party entrenched this exclusion. Afrikaner elites, with strong rural and Calvinist bases, racialised the pact further via apartheid legislation. In reaction, the Pan-Africanist Congress split from the ANC in 1959, accusing it of elite moderation and multiracial appeasement. As apartheid hardened, the Afrikaner state’s rule grew more authoritarian and centralised, especially between 1948 and the 1990s.

White English capital propped up the apartheid state and its mechanisms in exchange for access to cheap, surplus black labour and secure property rights.

Bantustanism extended the whites-only pact logic by delegating pseudo-sovereignty to handpicked black elites. Figures like Mangosuthu Buthelezi, Lucas Mangope and George Mathanzima gained prestige, salaries, and some local control, fostering envy among exiled ANC leaders sidelined by apartheid’s rigid racial hierarchy. These leaders, too, awaited their turn to ascend, setting the stage for a future elite pact under the guise of democracy or political freedom.

Thus, South Africa’s struggle history is also a story of elite contestation and accommodation, rather than always one of popular liberation.

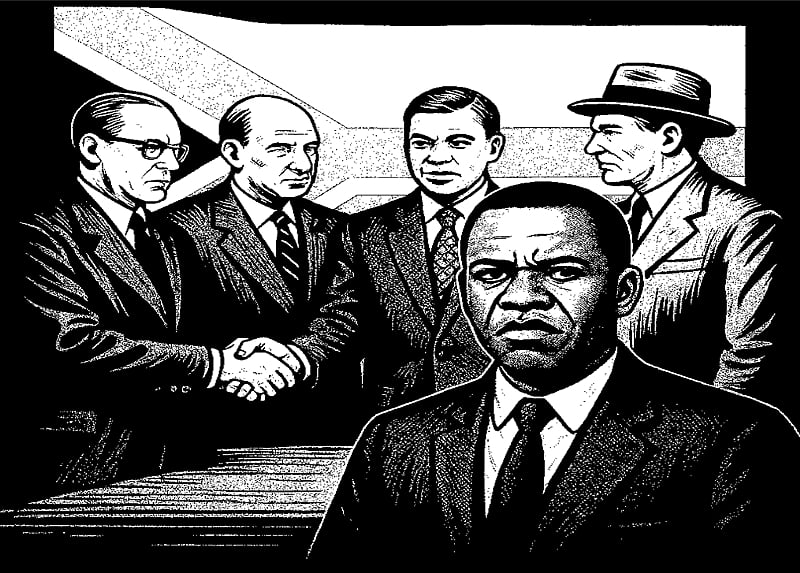

South Africa’s celebrated ‘miracle’ transition conceals a sobering truth: freedom was negotiated through elite pacts that prioritised stability over justice. The ANC and the Nationalist Party, along with entrenched white capital, made deals that ensured political change while protecting economic dominance. This foundational compromise, created in secrecy, embedded apartheid’s structural inequalities into democracy’s core, deliberately excluding the black majority from genuine economic liberation.

The effects are still felt painfully today.

The late 1980s witnessed secret talks between Nationalist Party leaders and imprisoned ANC figures, including Nelson Mandela. Confronted with sanctions and unrest, white capital initiated contact, seeking guarantees for their assets. These covert negotiations, bypassing democratic input, defined the narrow limits of the transition. As transitional scholars, Guillermo O’Donnell and Philippe Schmitter argue, such pacts inherently prioritise elite “vital interests,” inevitably marginalising broader societal demands for radical redistribution from the outset.

The CODESA negotiations formalised this elite bargaining. While multi-party, real power resided with the ANC and the Nationalist Party. The resulting Government of National Unity (GNU) of the time transferred political office but constitutionally protected white economic privileges and minority rights. In “Democratisation in South Africa: The Elusive Social Contract,” political scientist Timothy Sisk noted that the arrangement explicitly traded power-sharing for safeguarding existing wealth hierarchies, thereby fundamentally limiting transformation.

Democratisation occurred, but decolonisation did not.

Economically, the betrayal was clear. The ANC abandoned its highly questionable redistributive vision, as outlined in the Freedom Charter, especially nationalisation, under intense pressure. Yet the Freedom Charter itself reflected another form of elite pact-making, as it lacked genuine popular input. Its declaration that “South Africa belongs to all who live in it” overlooked the material realities of landlessness, dispossession, and exploitation endured by the black majority.

Dissenters like Anton Lembede, the radical founder of the ANC Youth League, rejected such liberal universalism and sought a mass-based, African-centred struggle rooted in material demands, rather than legalistic petitioning.

Pre-negotiation meetings, such as the 1985 Lusaka encounter between ANC exiles and white business, foreshadowed the neoliberal shift. Jo-Ansie van Wyk explains how an explicit “elite bargain” emerged: the ANC’s political power in exchange for maintaining the capitalist status quo. The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) was quickly discarded.

Its replacement, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) policy, enshrined market fundamentalism: privatisation, deregulation and fiscal austerity. This mirrored the NP’s own 1993 National Economic Model, revealing profound continuity. International financial institutions, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as well as domestic white capital, heavily influenced this dramatic ideological U-turn, prioritising investor confidence over mass upliftment. The economic foundations of apartheid remained disturbingly intact.

Black Economic Empowerment, purportedly designed to deracialise capitalism, evolved into “elite circulation.” A politically connected black minority gained access to ownership stakes and government tenders, joining rather than dismantling the existing economic oligarchy. Dale McKinley aptly describes this as a “two-headed parasite,” enriching connected elites while the black majority continued to suffer.

Affirmative Action policies, introduced to address historical workplace discrimination, did open doors for a segment of the black population in skilled professions and management. This led to the emergence of the ‘Black Diamonds,’ a visible, affluent black middle class. While significant for individual mobility, these gains often benefited those already positioned to seize opportunities, creating a stratified black society rather than broad-based economic upliftment.

As beneficiaries of elite pact-making, Black Diamonds reflect the tragic evolution of the Black Englishmen of the early 20th century. Their lifestyles mirror white consumption while their politics maintain the status quo. Many are disconnected from township and rural realities, reproducing the very inequalities their predecessors sought to dismantle. This insulated black elite has become both beneficiary and buffer of post-apartheid exclusion.

Genuine asset redistribution and the transfer of productive capacity were sidelined.

The outcome was a disastrous failure of the promised ‘double transition.’ Political democracy flourished in appearance, but economic inclusion came to a halt. Wealth inequality worsened. By 2022, the top 10% owned over 85% of wealth, with racialised patterns continuing. Unemployment skyrocketed, especially among black youth. Land reform made little progress.

The structural exclusion created by apartheid was replicated, not dismantled, under the new regime.

This elite pact-making produces what Thomas Carothers diagnosed as ‘feckless pluralism.’ Vibrant elections and a laudable constitution mask a system where real power resides with interconnected economic and political elites. Post-1994, grassroots movements and trade unions, the engines of apartheid’s downfall, were systematically marginalised or co-opted into elite power-sharing arrangements, through the ANC/SACP/Cosatu tripartite alliance. Decision-making is centralised within party structures, substituting elite consensus for popular participation.

The state’s potential as a development engine was hampered by its adherence to market orthodoxy and the safeguarding of historically accumulated privilege. Public services declined, affecting black townships and rural areas most severely. The social wage promised by liberation rhetoric failed to be realised on a large scale, unable to address deep-rooted inequalities.

The core principle of the pact – stability through elite accommodation – actively obstructed transformative state action.

The ANC’s 2024 electoral collapse, resulting in its loss of majority, led to the formation of a new GNU. Presented as ‘stability’ and ‘national interest,’ it eerily reflects the dynamics of the 1994 pact. The ANC partnered with the Democratic Alliance, the main defender of white capital interests, explicitly excluding parties advocating radical economic change, such as the EFF and MKP. That is not to say the latter is least interested in ascending to the exclusive elite club that runs the ‘new’ South Africa.

This new GNU, like its predecessor, was imposed without meaningful public consultation. Its stated priorities – ‘economic growth,’ ‘investor confidence,’ ‘fiscal discipline’ – directly echo the GEAR-era mantra, signalling continuity over change. DA demands focus on protecting existing economic structures and constraining state intervention, rather than redistribution. Land reform and national health insurance face renewed opposition.

Furthermore, the GNU embodies self-preservation. DA leader Helen Zille’s swift pledge to shield President Ramaphosa from accountability over the Phala Phala scandal clearly illustrates its core function: protecting elite interests across the political divide. Once again, the pact serves the powerful, not the populace. It prioritises managing the status quo over transforming it.

Thirty years after apartheid’s formal end, elite pact-making continues to be South Africa’s core governance process. The 2024 GNU is not unusual, but the latest version of a system formed in the CODESA backrooms. It aligns with Frantz Fanon’s insightful warning in The Wretched of the Earth: post-colonial elites often become a “new bureaucratic aristocracy,” perpetuating exclusion under new banners. Liberation remains sadly limited to the ballot box.

The DA, backed by settler capital and a rhetoric of colour-blind liberalism, has long resisted redistribution. That the ANC—founded to resist white settler unity—now governs in alliance with it, is a bitter historical irony. As the DA’s foreign policy posture shows, white privilege continues to shape South Africa’s role in the world, often against the interests of the black majority.

Yet resistance has not vanished. Movements like Abahlali baseMjondolo, the Amadiba Crisis Committee, and landless rural women’s networks are reviving mass-based, participatory politics outside elite pacts. Their democratic imaginations challenge both the procedural limits of electoralism and the material violence of dispossession.

A different future remains possible. But it requires rupturing elite continuity, rejecting symbolic inclusion and forging a mass, redistributive democracy where dignity is not aspirational, but lived.

Siya yi banga le economy!