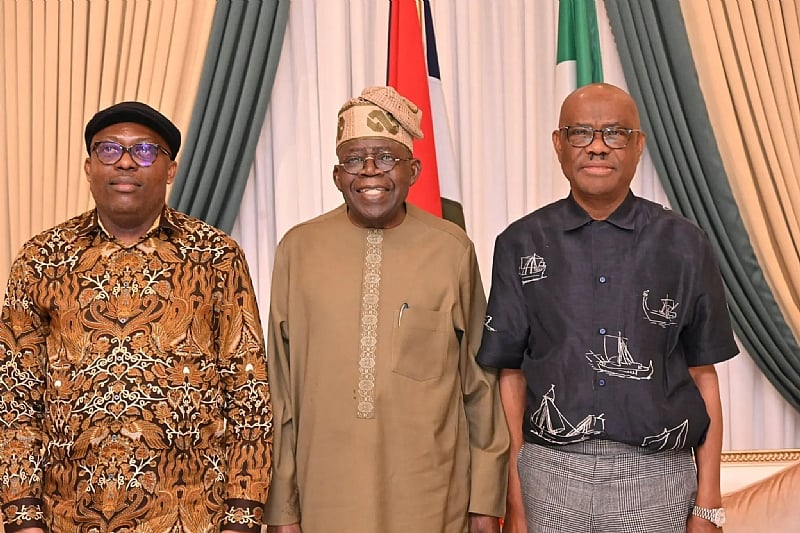

The imminent reinstatement of Siminalayi Fubara as the governor of Rivers State following a truce brokered by President Bola Ahmed Tinubu may on the surface appear to be a move to restore peace to the politically embattled state. However, when examined through a more critical lens, the conditions attached to his reinstatement raise a far more alarming question: Will Fubara’s returne to Government House turn him to nothing more than a rubber stamp governor, stripped of real power, shackled by political blackmail, and sentenced to serve at the mercy of a godfather?

Let us not mince words, what has been passed off as a “peace deal” is nothing short of a constitutional aberration, a brutal slap to the very principles of democracy and political sovereignty. How can a sitting governor, elected by the will of the people, be forced into a humiliating agreement that not only bars him from seeking re-election in 2027 but also compels him to relinquish control of all 23 local government areas to his political rival and predecessor?

Worse still, Fubara is to pay all outstanding allowances and entitlements to the same 27 lawmakers who defied the democratic process, defected to another party, and attempted to impeach him. In return for what? Peace? Or more accurately, silence in exchange for subservience?

Let us be brutally honest: this is not reconciliation; it is coercion dressed in diplomatic garb. It is a political deal that screams of imbalance and injustice. In the name of ending a crisis, the Rivers people have now been presented with a governor whose hands have been tied behind his back. And if history teaches us anything, such compromises seldom restore democracy, they erode it.

While reading the story as reported by the Cable, the thought that came across my mind was “Is rubber stamp governance in the making in Rivers State? The answer to the foregoing thought-provoking question cannot be farfetched as the terms of reconciliation spelt out for the governor are eloquent enough.

Without a doubt, Fubara has effectively been boxed into a corner. His ability to govern independently has been neutered. With the control of local governments handed over to Wike, the political muscle and grassroots machinery that drive governance in Rivers State now lie elsewhere. For those who understand Nigerian politics, local government control is not a small concession. It is the engine room of state-level power, influencing everything from revenue disbursement to voter mobilization. So what would Fubara be controlling when he comes back in September? This is as the lawmakers would be working with Wike, and not the executive. So, contrary to Montesquieu’s proposition, Rivers now has one of the arms of three arms of government as Wike would automatically become the legislative arm.

In fact, Fubara would be in office in the remaining days of his tenure without the local councils as they will be filled with Wike’s loyalists. As for his political future, he has already been told not to dare think of 2027. If this is not the textbook definition of a rubber stamp governor, then what is?

Without a doubt, Nigerian democracy has long been plagued by the suffocating grip of godfatherism, and the Rivers situation is another painful reminder. What Wike has demonstrated through this deal is that even after leaving office, he still wields the real power. The office of the governor has become symbolic, while the machinery that drives governance is firmly in the hands of a man who has refused to let go.

In other democratic societies, the transition of power is supposed to mean the handing over of both responsibility and authority. But in Nigeria, the emergence of governors who operate under the shadow of overbearing godfathers has become the norm. Tinubu’s peace deal essentially legitimizes this backward political tradition.

What does this say about Tinubu’s leadership? The answer to the foregoing cannot be farfetched as President Tinubu’s decision to broker a deal that clearly favors one side raises serious questions about his commitment to federalism, justice, and fairness. If this is how political disputes are to be resolved under his watch, by forcing sitting governors into silence, stripping them of autonomy, and handing power back to former leaders, then Nigeria’s democracy is on a dangerous path.

Yes, a political crisis needs to be managed, but not at the cost of decimating the foundational structures of governance. Tinubu’s appointment of a sole administrator during Fubara’s suspension was already undemocratic, but this latest maneuver is worse: a democratic governor has now returned, not with renewed power, but with diminished dignity.

In fact, the so-called reconciliation is unarguably a mockery of the Rivers mandate. Let us not forget that Siminalayi Fubara was not appointed, he was elected by the people of Rivers State. That mandate was not given to Bola Tinubu, not to Wike, and certainly not to the 27 defecting lawmakers. By negotiating away Fubara’s political future and executive powers, the so-called peacemakers have also negotiated away the mandate of the Rivers electorate.

At this juncture, it is germane to ask, “Who speaks for the people in all this?” “Who consulted the millions who voted Fubara into power?” “Are their votes now worthless in the face of backdoor agreements, elite handshakes, and closed-door betrayals?”

Ironically, some defenders of the deal argue that the priority is peace and stability. But the question must be asked: Peace for whom? Political elites may have secured a ceasefire in their selfish turf war, but what about the long-term implications for governance, development, and accountability in Rivers State?

Peace that is bought through the muzzling of a sitting governor is not peace, it is submission. Peace that denies voters a right to continuity and progress is not peace, it is suppression. And peace that empowers a political strongman while emasculating a democratically elected leader is not peace, it is dictatorship in disguise.

Given the unprecedented development in Nigeria’s democratic history, it is expedient to ask, “What happens to governance now?

With Wike effectively running the show from Abuja and local government leaders answering to him, Rivers State is now being ruled remotely. Fubara will remain the ceremonial head, a rubber stamp governor, attending events, reading prepared speeches, and signing documents crafted in the background. But the real levers of power, appointments, funding, policies, will likely no longer be in his hands.

“Can a governor govern without mutually working with the lawmakers?” Without loyal local government chairmen? Without the promise of a second term to consolidate policies? If your answer is “no,” then you must agree: Fubara is being turned into a placeholder, rubber stamp, nothing more.

Looking at the issue the lens of a bigger picture, it cannot be erroneous to opine that what is unfolding in Rivers State is bigger than Fubara. It is a signal to every other governor and politician in Nigeria: challenge the system, and you will be cut down to size. Assert your independence, and you will be politically kneecapped. Seek to stand without a godfather, and you will be told to sit, or be removed entirely.

It is a dangerous precedent, one that undermines democratic principles and empowers political puppeteering. We are fast becoming a nation where elections are just a formality and real power lies with whoever controls the political machinery behind the scenes.

On final thoughts, it is germane to opine that Siminalayi Fubara’s imminent reinstatement, under the terms agreed upon, is not a victory for democracy. It is a victory for coercion, for political subjugation, and for the entrenchment of godfatherism. It reduces the office of governor to a ceremonial role, strips the people of Rivers State of their right to genuine representation, and sends a chilling message to would-be reformers across the country.

So again, we ask: “Is Fubara now just a rubber stamp governor?” The answer, sadly, seems to be yes. And if Nigerians do not push back against this kind of elite hijacking of democratic processes, many more governors may soon find themselves in the same pitiable situation.

It is not too late for the people of Rivers, and Nigerians at large, to demand more from their democracy. Because once leadership becomes a commodity traded behind closed doors, we are all just spectators in a play whose script we did not write, and whose ending we would not like.