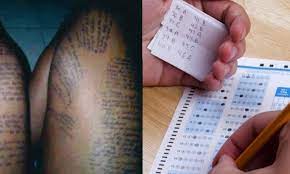

In recent years, Ghana’s educational system, once held in high esteem across West Africa, has been gripped by an unsettling reality: the normalization of examination malpractices, particularly during the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) and the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE). What once was a matter of personal dishonesty has now evolved into a deeply entrenched, systemic problem that threatens the intellectual, ethical, and national fabric of the country.

It is increasingly disheartening to observe teachers, who are meant to be the moral and intellectual guides of their students, openly facilitating cheating in the name of “helping” candidates pass. During examinations, it is no longer uncommon to find teachers printing out answers on A4 sheets and distributing them boldly in examination centers. These disgraceful acts often occur with the silent endorsement, or outright collaboration, of some corrupt officials from the West African Examinations Council (WAEC), and in more disturbing instances, security officers stationed to maintain order and integrity. Their complicity is typically secured by bribes offered through candidates or their parents, turning the examination hall into a well-coordinated theatre of academic fraud.

The most troubling aspect of this phenomenon is not just the corruption itself, but its consequences. Students who pass examinations through such fraudulent means proceed to the next stages of their academic journey without the foundational knowledge required to succeed. Because they have not earned their grades, they feel no motivation to study, to improve themselves, or to respect those who genuinely try to guide them. Ironically, these same students often show blatant disrespect to their teachers, many of whom compromised their own integrity to ensure those students succeeded through dishonest means. Sadly, the moral decay is so deep that teachers are vilified by the very students they helped cheat, and even their parents support the impunity.

The long-term implications are grave. Some of these unqualified students find their way into nursing training institutions, where they struggle to understand the basic medical knowledge required to save lives. Their incompetence becomes dangerous when they graduate and begin issuing wrong prescriptions, endangering the lives of innocent Ghanaians. Others make it to the universities through the same fraudulent system, only to be overwhelmed by academic demands they are intellectually unprepared for. Frustrated by mounting failures and repeated trails, some of these students resort to violence, drug use, or join campus gangs in an attempt to find identity and escape the pressure of exposed inadequacies.

More frightening is how this cycle of dishonesty spills over into national institutions. Students who cheat their way through school often enter Ghana’s security services – police, immigration, military – not by merit, but through fraudulent certificates and corrupt networks. These are the very people who are later expected to uphold law and order, yet their entire journey to power has been paved by lies and bribery. They enforce the law with the same corrupted mindset that got them into uniform. In politics, the situation is no better. Individuals who built their careers on counterfeit academic foundations carry that same rot into leadership positions, making decisions not based on knowledge or wisdom, but personal interest, deception, and greed. Even within our banks, civil service, and other notable agencies, the fingerprints of exam malpractice are evident in the lack of professionalism, integrity, and competence.

Teachers, who should be the standard-bearers of academic integrity, are often driven to such malpractice due to poor working conditions. Many educators, especially in rural and basic schools, are underpaid, overwhelmed, and undervalued. Their payslips are often littered with loans, either because of poor financial planning or simply because their salaries cannot sustain them. Out of financial frustration, some compromise their values and engage in these dishonest acts during BECE and WASSCE. To add insult to injury, after enabling students to cheat, some teachers are shortchanged and denied the full sums they were promised, leading to arguments and even fights over unpaid “exam help” fees. This disgraceful scenario undermines the nobility of the teaching profession and reduces it to a transactional hustle.

It is undeniable that the government bears a significant portion of the blame. Teachers in Ghana are not remunerated in accordance with the weight of their responsibility. If the nation desires integrity and excellence in its educational outcomes, then it must first begin by treating teachers with dignity. Government must commit to improving the living and working conditions of teachers. Policies should be enacted to provide affordable housing schemes, and more importantly, the state should sponsor at least three children of every teacher from basic school up to the university level as a token of appreciation for their indispensable contribution to society.

Parents too have a role to play. Rather than colluding in this malpractice by paying for leaked questions and encouraging cheating, they must prioritize supervising their children’s study routines, creating a culture of discipline at home, and discouraging them from street life and laziness. Education must be viewed as a partnership among the home, the school, and the state. A parent who pays to help their child cheat is not investing in their success – they are complicit in their eventual failure.

A more alarming trend is how some private schools, especially in the former Brong Ahafo Region, have turned examination malpractice into a business model. These institutions are advertised as guaranteed centers for “apor,” where students pay large fees in exchange for ensured assistance during exams. The owners, staff, and even some examiners turn this into a profit-making venture, with little concern for the future of the children they are misleading.

In some Senior High Schools, final year students are even compelled to pay “exam helping fees” which are then distributed among teachers, invigilators, security officials, and sometimes WAEC insiders. These arrangements create a disturbing cycle of exploitation and fraud that mocks the entire purpose of education.

As a country, we must rise up to confront this reality. The recent ruling by the Kintampo Circuit Court on 16th June 2025, which sentenced some teachers to 30 days of hard labour for participating in exam malpractice, is a step in the right direction. But it must not end there. If a student does not learn and fails an exam, they should be allowed to repeat. Failure should not be treated as a disgrace, but as an opportunity to try again and do better. Ghana Education Service (GES) must also consider reinstating some level of controlled, humane corporal punishment in schools to restore discipline and command respect, especially in public basic schools where teacher authority has been severely eroded.

Until we confront and dismantle the structures that allow cheating to flourish, we will continue to graduate students who cannot spell their names, nurses who endanger lives, officers who brutalize rather than protect, and politicians who steal instead of serve.

Ghana’s educational system is not just about preparing students for exams; it is about raising a generation that is competent, ethical, and ready to contribute meaningfully to national development. If we fail to uphold honesty and merit in our schools, then we are laying a rotten foundation for our nation. It is time to stop the rot, no matter how deeply it has taken root.

By Francis Anwulibo Jebuni

Bamboi

A concerned educator and advocate for integrity in Ghana’s educational system.