Ghana’s mining sector has come under scrutiny for human rights abuses, environmental destruction, and economic injustices that disproportionately affect local communities.

A report by WACAM, titled “History of Human Rights Violations in Ghana,” presented during a media engagement organized by the Centre for Public Interest Law (CEPIL) and supported by WACAM and Oxfam, revealed how some mining companies continuously violated the rights of people living in the Ahafo Ano North and Akyem areas.

Presented by Mrs. Hannah Owusu-Koranteng, Associate Executive Director of WACAM, the report detailed how mining companies, in collaboration with state security agencies, used force and intimidation to suppress local community members.

The trend has been a pattern of arbitrary arrests and detentions of activists and suspected illegal miners in private holding facilities, which is a clear violation of Ghana’s constitutional protections against unlawful detention.

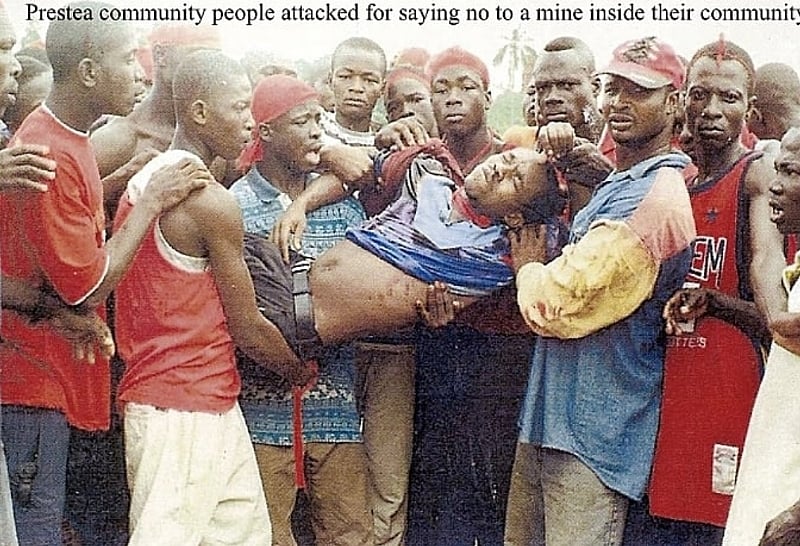

The right to peaceful protest is enshrined in Ghana’s 1992 Constitution. However, community members who attempt to exercise this right often face brutal crackdowns.

Disturbing reports indicate that security forces have shot at demonstrators in communities including Tebrebe, resulting in severe injuries. Some of these incidents resulted in deaths.

In communities such as Saamang and Prestea, residents have reported security raids targeting people who protested against mining-related destruction of their water sources and livelihoods.

In a video documentary, community members shared their stories about how several communities lost their farmlands and homes to mining companies, with support from state agencies, through coercion, manipulation, and outright force.

Communities affected include Techire, Yamfo, Susuanso, Aduasena, New Abirem, and Yaw Tano. Community members were told to halt any development on their buildings with the promise of resettlement.

“None of the things they promised to do for us materialized… At the time, I had built my three rooms and I was living in one, and was about to continue building more rooms. They told me to stop. I shouldn’t even bother to plaster the rooms, with the promise that they would build for me and give me electricity, and so I stopped.

“When time was due for resettlement, they said I was occupying only one room in my old house and so they were only going to build one for me,” Kwame Denkyere Snr, a farmer at New Abirem said.

Others were given six months’ rent allowance and were forced to vacate their homes. In the case of women, only 3.1% of them received compensation.

“They were using police to even drive us away from our land before they degraded the lands,” Joseph Aduyaw, also a farmer at Techire in the Ahafo Region narrated.

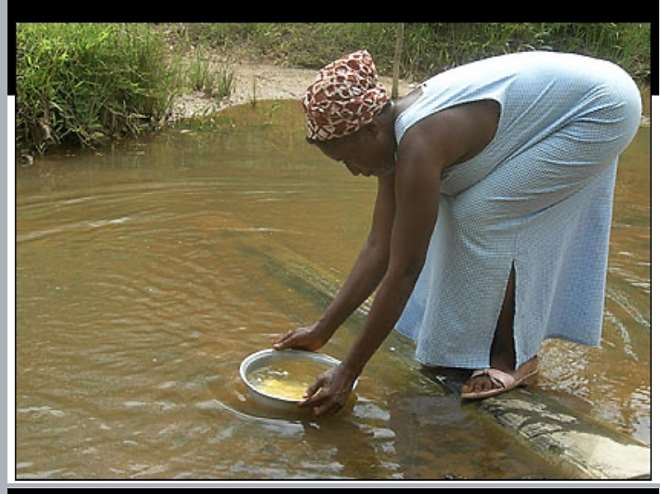

Research by WACAM indicates that about 250 water bodies in the Obuasi and Tarkwa areas were polluted. Underground water has also been polluted with heavy metals through seepages and spillages of mine waste.

Water samples tested in various locations revealed heavy metal concentrations far exceeding WHO and USEPA guideline values. At Aprepre, arsenic levels reached 1.984 mg/L, cadmium 0.276 mg/L, lead 1.250 mg/L, and manganese 1.235 mg/L. At Bodwire, arsenic measured 1.469 mg/L, cadmium 0.063 mg/L, lead 0.512 mg/L, and manganese 1.563 mg/L. At Asasre, arsenic levels stood at 0.220 mg/L, cadmium 0.356 mg/L, lead 0.008 mg/L, and manganese 1.345 mg/L. Other affected communities include Ben, Nana Panipa, Twiagya, and Kwakronkron Nsuabena.

A borehole tested at Dumase revealed metal concentrations of 0.048 mg/L for arsenic, 0.032 mg/L for cadmium, 0.105 mg/L for lead, and 1.89 mg/L for manganese.

These values significantly exceed WHO’s safe limits of 0.01 mg/L for arsenic, 0.4 mg/L for cadmium, 0.05 mg/L for lead, and 0.015 mg/L for manganese, as well as USEPA’s guidelines of 0.01 mg/L for arsenic, 0.5 mg/L for cadmium, 0.4 mg/L for lead, and 2.0 mg/L for manganese.

Additionally, there have been reports of companies, including Newmont Ahafo Mine and AngloGold Iduapriem Mine, discharging fecal matter into community streams.

As a result of these mining activities, health risks have increased, including a rise in respiratory tract infections, malaria incidence, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and occupational health and environmental diseases.

Mining activities have also encroached on critical forest reserves, including Kubi, Tano Suraw, and parts of the Nueng Forest Reserve. Ghana is currently ranked among the top three countries in the world experiencing rapid deforestation, following Nigeria and Togo.