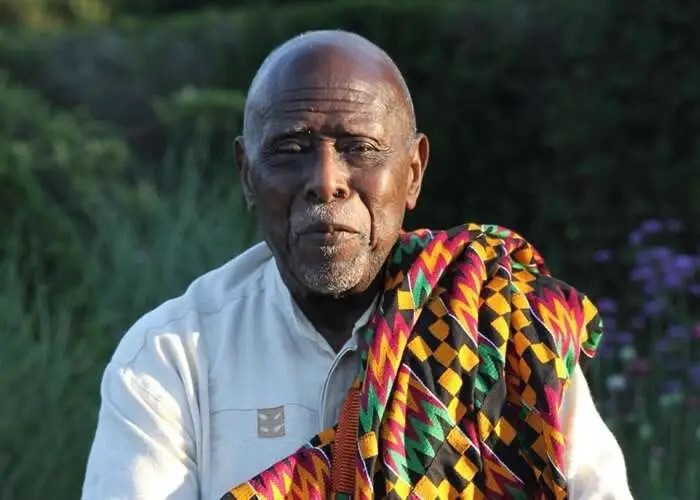

With the passing of Dr Felix Israel Domeno Konotey-Ahulu so soon after that of Dr Graham Sarjeant, two pioneers who conducted extensive research into sickle cell disease, there is an undeniable vacuum in the global sickle cell community, and we shall all miss his robust responses in the various medical journals on sickle cell issues.

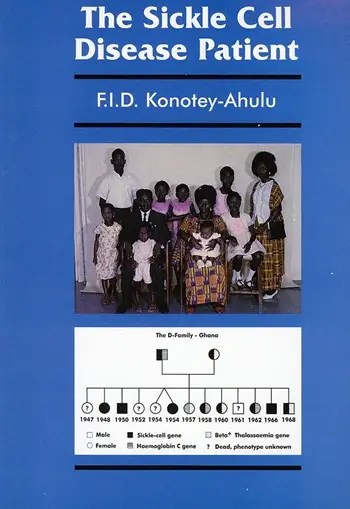

Dr Konotey-Ahulu was, by all accounts, an excellent physician, scientist and scholar who took it upon himself to champion the cause of patients of a disease which, despite being discovered over a century ago, remains incurable for most patients. His original work was in setting up the largest sickle cell clinic in the world, which became known as the Ghana Institute of Clinical Genetics. The protocols that he introduced and which have now been adopted worldwide were way ahead of any treatments and care for patients born with sickle cell disease.

As a child, I often suffered frequent bouts of illness that caused my parents untold anguish, especially since my older sister did too.

I started my secondary school education as a boarder just before I turned 10 years and nothing had changed. The school authorities were very concerned about my health challenges – being so young, they wondered whether I was malingering, or simply homesick or if there was more to my frequent bouts of illness. The doctor assigned to Achimota School, Dr Kuta Dankwa, decided that a referral to Korle Bu Teaching Hospital for further investigation would help shed some light on the situation.

It was at Korle Bu that I first met Dr Konotey-Ahulu and Dr Portuphy Lamptey and was admitted to the Children’s Ward under the care of a lady doctor, Dr Kuma. It was Dr Konotey-Ahulu who explained the findings of their investigation to me in a way that, although I did not fully grasp the science he was talking about, made sense. His bedside manner was very reassuring, and I can still recollect to this day some of the words he used to explain what was happening to me.

The explanation was simply this, what my parents believed to be rheumatism was in fact what our ancestors refer to as “tweweetwe” and had nothing to do with suggestions that witches sucking my blood was the cause of my blood disorder. The disease was in the blood that I had inherited from both my parents. He made me promise to introduce any potential future life partner to him for testing and counselling so that our children would be spared a life of pain and discomfort. I kept that promise. On reflection, that was the first lecture I received on genetic counselling and also the assurance that I could live a longer life than most thought possible or probable.

From then on, this remarkable physician specialist cared for me and others like me, showing a genuine interest in their health matters, as I can say that he did for his own children. His passion for genetic counselling led him to create a pool of peer patient counsellors who shared their stories when they met at the clinic or during their stay in Medical Ward 2, where he lobbied to have most of the sickle cell patients admitted.

When taking the medical history of his patients, he was particularly skilled at encouraging them to ask questions and to keep a record of events that triggered their crisis. If a crisis was triggered by an infection, his preferred treatment was rehydration and a course of prescribed antibiotics instead of painkillers. In my twenties, he often told me off for living it up like a typical young man of that age, putting myself under unnecessary stress, which was often a result of overindulgence. He was usually right, especially when I ended up on admission to the hospital as a consequence of my lifestyle. For me, it was all about enjoying life as a young man because you are only young once!

Dr Konotey-Ahulu set me on the path of activism and advocacy for sickle cell when he joined some of us patients in the fight against the futile attempts by passenger airlines to deter and prevent sickle cell patients from travelling on their planes and embarked on a campaign to force airlines to pressurise their passenger planes instead. He also campaigned against using urea for treatment because there were no benefits.

In 1976, he received a Guinness Award for Scientific Achievement that enabled him to tour the UK. During this time, I was hospitalised for a hip bone problem, and he made time to hold a lengthy discussion with me about my health. I can say that his repeated advice on doing everything in moderation finally struck a chord and changed my attitude toward my lifestyle.

In the early eighties, I saw him a couple of times at his office in Harley Street, he was kind enough to waive his charges and at Cromwell Hospital where he conducted health MOTs on me. Although I was now under the care of a haematologist, I benefited immensely from the free medical advice he very generously gave me over the years. He often called on me to accompany him to lectures he gave so that I could answer questions on sickle cell disease from a patient’s perspective. He always let me know about and sought my views on any articles on sickle cell issues in the medical journal. Our most recent discussion was about a cure that is supposed to have been found for the disease.

Our relationship developed from one of patient-doctor into one of nephew-uncle because of our shared interest in GaDangme issues. He devised an innovative system for writing the language that would make it easier to read, as I continue on my search for identity through the customs and traditions of the people.

Dr Konotey-Ahulu was very kind-hearted, and I witnessed his kindness when a very good friend of mine was going through a mental health crisis and was about to be sectioned by the police. He did not hesitate to drive down from Watford to London to rescue her from the police. His timely intervention resulted in the lady being checked into a private clinic for the care that she needed.

Dr Konotey-Ahulu, son of a reverend minister, was a staunch Christian and remained so to the extent that he disagreed with some of the facts that underpinned his work as a scientist. I shared weekly devotionals in Ga from Pastor Dowuona-Hammond with him, and he reciprocated by sending me daily sermons by Rev Ofoli Quaye, also in Ga.

Suffice it to say that all of us, patients in the global sickle cell community, have lost an ardent activist whose conviction was that scientists should focus on patients and that their care should be the primary reason for the science. In truth, he spoke more sense than science.

His family already know that a great man has passed, and I would like to end this tribute with these words in Ga:

Osofobi Domeno, Klo Hiŋmɛi, yaa wo ojogban yɛ oNuntsɔ lɛ minshi.

Ade Sawyerr

Croydon

Ade Sawyerr is a management consultant at Equinox Consulting who works on enterprise, employment and community development issues within the inner city and black and minority communities in Britain. He comments on social, economic and political issues and can be contacted at www.equinoxconsulting.net or [email protected].