Members of the notorious British Punitive Exhibition of 1897 posing proudly with looted Benin ivories and bronze objects.

Members of the notorious British Punitive Exhibition of 1897 posing proudly with looted Benin ivories and bronze objects.The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, will return to Robert Owen Lehman twenty- seven Benin artefacts while keeping five of the artefacts that the museum received in 2012 as donations. (1)

The museum wanted Lehman to complete the transfer of ownership rights as had been promised and expected. With full ownership rights, the museum would have worked out an arrangement with the Oba of Benin, the legitimate owner of the artefacts that the British had stolen in the notorious 1897 invasion of the Kingdom of Benin, now in Nigeria.

As discussions between the museum and Lehman had gone on for a long time without any visible progress, Lehman requested the museum to return the artefacts. As a result, the museum will return the Benin artefacts to Lehman and close on April 28, its Kingdom of Benin Gallery, which was opened with a lot of pomp and fanfare in 2013. The press reports on this matter are based on statements from the Boston Museum. Lehman refused to comment. The museum’s director is reported to have declared:

‘ The MFA was the first American museum to launch a colonial-era provenance project. We strive to be a leader in ethical stewardship and reaching judicious restitution decisions.’ (2)

The MFA tries to give the impression that it was seeking full ownership rights from Robert Lehman to negotiate with the Oba of Benin arrangements that are ethically acceptable. ‘The museum said the means by which Lehman came into possession of many of these objects prompt questions how to display these works ethically.’ (3)

The MFA’s attempt to project an ethical image is not very convincing. How can the museum keep any looted objects from the Lehman Collection after the institution had described the collection as having dubious origin?

Readers should be under no illusion about the ethical principles or morality the MFA is pursuing. Readers will recall that at the time of donating these ill-gotten artefacts, there were several criticisms of the museum’s acceptance from the entire world. The Nigerian National Commission, NCMM, requested the MFA to return the looted articles to Nigeria immediately. This author, then and for several years thereafter, criticized the museum for the illegality, illegitimacy, and immorality involved. (4)

Trying to negotiate an ethically acceptable arrangement of looted artefacts is essentially either a deceptive presentation or an illusionary approach. There is no way one can hold ethically stolen objects unless the ownership issue is settled with the original owner, separately from the wishes of the present holder for future loans. The MFA cannot make the desire for a future loan a condition sine qua non for agreeing to transfer ownership rights. The Oba and the MFA can only discuss future loans ethically after they have settled present ownership issues.

One can observe from the announcement of the impending closure of the Benin Gallery, that the MFA has not fully understood the wide dimensions and implications of the present debate on restitution:

‘The objects going on view in the adjacent Art of Africa Gallery include a commemorative head, a pendant showing an oba and two dignitaries, a relief plaque showing two officials with raised swords, and a relief plaque showing a war chief with two attendants—all of which are in the MFA’s collection. In addition, the MFA will retain and display one loan from Lehman, a bronze commemorative head of a defeated leader outside the Benin Kingdom by the 1880s and not subject to the looting of 1897.

In the near future, the gallery will be turned into a space for displaying the MFA’s renowned collection of Nubian art. A small selection of Nubian objects will go on view beginning May 1. Highlights include shawabties (funerary figurines) of King Taharqa, the most powerful of Nubia’s rulers, and finely decorated pottery from the Meroitic period, during which the kingdom flourished and participated in trade and cultural exchange across the Mediterranean. A more robust display will follow in the coming years after the conclusion of a major touring exhibition.’ (5)

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, seems to regard itself as legal and legitimate owner of ‘a commemorative head, a pendant showing an oba and two dignitaries, a relief plaque showing two officials with raised swords, and a relief plaque showing a war chief with two attendants—all of which are in the MFA’s collection’

.

How can we be sure that these objects were legitimately acquired? The MFA will even’ retain and display one loan from Lehman, a bronze commemorative head of a defeated leader, which was outside the Benin Kingdom by the 1880s and not subject to the looting of 1897.’

That an object was outside the Benin Kingdom by the 1880s does not imply it was acquired in an ethical way. This date does not say anything about how the object was initially acquired, ethically, morally, or with violence. Most authorities on Benin artefacts suggest that before the 1897 invasion, there were no Benin artefacts outside the Benin Kingdom. Felix von Luschan, the German authority on Benin artefacts, declared that before the 1897 invasion, such artefacts were unknown in Europe. Benin artefacts were produced by specialist bronze casters, recruited and paid by the Oba to work for him alone, and thus, any such piece that came to the market must have been illegally taken.

Moreover, the MFA announced its intention to display the treasures of another African civilization. Do we know that the Nubian treasures were legally acquired? When I read what is written about George Reisner, who is credited to have excavated the Nubian treasures, I start wondering whether everything was legally and correctly done.

‘Reisner’s views on Nubia were conditioned by the theoretical ideas of his own time, many of which were based on racist considerations about the progress and decline of cultures. From his perspective, the subsequent stages of Nubia civilization were the result of the influx of external peoples that migrated into the country. He deemed the local black populations incapable of the artistic or architectural achievements he faced during his excavations. He postulated the Egyptian origins of the Kushite culture since they were considered somewhat closer to the Caucasian stock. Modern scholarship has recently disregarded these ideas, emphasizing the many links between Ancient Egypt and Ancient Nubia and even advancing the statement that Nubia had a strong influence over Egypt, especially during prehistoric and early historical times.’ (6)

We recall also the history of Ludwig Borchardt and the excavation of the bust of Nefertiti in Egypt. Cuno and others have indicated that the division of archaeological results, so-called partage, was not always fair to the land that allowed excavation, mostly under colonial or semi-colonial rule. Zahi Hawass could tell us more about the acquisition of artefacts under colonial and semi- colonial regimes by Western museums and institutions. (7)

The MFA does not show any awareness that all African treasures in Western museums are under general suspicion of having been illegally or illegitimately acquired. The determination to show treasures of another African kingdom before the ethical issues concerning the Benin artefacts have been resolved may appear as defiance to the spirit of our times and a provocation to restitution activists.

The demand for restitution of looted African artefacts applies to all African objects that are in Western museums and were acquired with violence or under dubious circumstances. Benin artefacts are but examples of stolen objects.

Asante, Baule, Bambara, Dogon, Dan, Egyptian, Ethiopian, Fon, Gouru, Kuba, Luba, Lobi, and other treasures are still to be returned to their owners. Western museums should not think that the restitution of one or two Benin objects solves the problem of reparatory justice for all the African peoples deprived of their artefacts during colonial rule. Recent research has revealed again the extreme violence of colonial rule. (8)

It is not enough to return the Benin artefacts to the illegal holder. What about MFA’s participation in detaining the Benin artefacts, knowing fully well they were looted? We should note that it was not the MFA that, out of moral revulsion, returned the artefacts to the illegitimate holder. On the contrary, the holder asked that the objects be returned to him. Did the MFA try in all those years to suggest to the Oba of Benin and Robert Lehman to enter direct negotiations to resolve the issues of ownership? The MFA tried to secure ownership rights in objects that the MFA has characterized as looted. What morality allows such behaviour? Had the MFA obtained what it sought, would the institution have been in a hurry to let the Oba have his treasures back? Or would the American museum have kept the objects as long as the parties had not finalized discussions and continued displaying the looted objects to a fee- paying public?

Are there no damages payable for participating in violating the rights of the Oba of Benin and the Benin people? Participation in the opening of the Kingdom of Benin Gallery does not deprive Benin of due compensation for the denial of the right to independent cultural development. But did the Oba officially participate in the opening ceremonies and events after the Nigerian National Commission had formally and strictly requested the return of the artefacts? (9)

What does the MFA aim to achieve by continuing to display objects the institution itself has described as looted or of dubious origin? Is the public or MFA in any way served by viewing stolen items? Is the aesthetic pleasure of a few artefacts more important than restoring justice and morality in a world seriously threatened by powerful forces that mistake might and force for law and justice?

Does the MFA not have any obligation to contribute to resisting oppression and violation of human rights, including the right to cultural development with our cultural artefacts?

Are some persons entirely impervious to the cries and woes of the African peoples who have been demanding the return of their artistic and religious treasures, looted with great violence under the notorious colonial empires? If on the other hand, institutions, such as museums, have become purely commercial enterprises that are only concerned with their profits regardless of sources and are not impressed by appeals by leaders, such as the late Pope Francisco, to return looted artefacts, they should let us know.

They should not pretend to be striving for ethical stewardship or any moral standards in matters of looted artefacts. They would help us to free ourselves from the illusion that it is still possible to expect considerable and meaningful restitution of looted African artefacts from Western museums and institutions that have refused for decades to comply with UNESCO/UNITED NATIONS decisions and recommendations to return stolen cultural property to their countries of origin. We will then know it was just a game. In the meanwhile, there are a few things Western museums could do to facilitate relations with African countries.

· Western museums should understand the African demand for restitution in its true dimensions, affecting all African artefacts under their control. The African Union has proclaimed the theme for 2025 as justice for Africans and Peoples of African descent through reparations. Restitution is inherent part of this effort for reparatory justice.

Museums should finally pay attention to UNITED NATIONS/UNESCO resolutions on the return of cultural property to their countries of origin and observe the ICOM Code of Ethics. Western museums have routinely ignored the resolutions of the highest world representative bodies. Western museums should publish lists of their holdings with photos and information on the sources of their objects, including country of origin and mode of acquisition. Western museums should cease presenting arguments against restitution that have been refuted long ago, especially when such defences are obviously aimed at gaining time. For example, a museum should not declare that the Nigerian Government has not recently renewed its claim for the restitution of the Benin artefacts. (10)

But let there be no mistake. Looted African cultural artefacts will return home.

NOTES

1. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to Close Benin Kingdom Gallery on April 28

https://www.mfa.org/press-release/mfa-to-close-benin-kingdom-gallery

MFA Boston to return Benin Bronzes to wealthy donor, close gallery

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/04/25/museum-fine-arts-boston-benin- bronzes-robert-owen-lehman

Museum’s Benin Bronzes Are Reclaimed by Wealthy Collector

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/25/arts/design/benin-bronzes-museum-fine- arts-boston-lehman.html

In an extraordinary move, MFA to return prized African art to wealthy donor and close gallery.

https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/04/22/arts/benin-bronzes-lehman-return- plunder-museum-of-fine-arts-mfa-boston/

2. MFA Boston to Rescind Promised Gift of Benin Bronzes, Close Dedicated Gallery https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/mfa-boston-to-rescind-

promised-gift-of-benin-bronzes-close-dedicated-gallery/ar-AA1DpJ58

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to Close Benin Kingdom Gallery on April 28https://www.mfa.org/press-release/mfa-to-close-benin-kingdom-gallery

3. https://www.wgbh.org/culture/visual-arts/2025-04-22/mfa-to-close-benin- kingdom-gallery

4. Nigeria demands return of disputed artefacts acquired by Boston’s Museum

of Fine Arts

of Fine Arts

https://www.elginism.com/similar-cases/nigeria-demands-return-of-disputed- artefacts-acquired-by-bostons-museum-of-fine-arts/20120725/4876/

K. Opoku, Will Boston Museum of Fine Arts Return Looted Benin Bronzes?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/438346/will-boston-museum-of-fine-arts- return-looted-benin-bronzes.html K. Opoku, Blood Antiquities in Respectable Havens: Looted Benin Artefacts Donated to American Museum

https://www.modernghana.com/news/405992/blood-antiquities-in-respectable- havens-looted.html

K. Opoku, Is the Museum of Fine Arts Boston Serious about the Restitution of Looted African Artefacts? https://www.modernghana.com/news/1128195/is-the-

museum-of-fine-arts-boston-serious-about.html K. Opoku, Have Ethical Considerations Returned to Restitution for Good? Smithsonian Adopts a Policy on

Ethical Return https://www.modernghana.com/news/1162776/have-ethical- considerations-returned-to-restitutio.html K. Opoku, Reflecting on what can be done to recover African artefacts https://www.elginism.com/similar-

cases/reflecting-on-what-can-be-done-to-recover-african- artefacts/20120723/4864/

5. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, to Close Benin Kingdom Gallery on April 28

MFA press release https://www.mfa.org/press-release/mfa-to-close-benin- kingdom-gallery

6. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/George_Andrew_Reisner

7. K. Opoku, Does Dr. Cuno Really Believe What He Writes?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/604674/does-dr-cuno-really-believe-what- he-writes.html

See James Cuno, Who owns Antiquity? Princeton University Press, 2008, pp.14, 55 and 154.

‘Under the British Mandate, from 1921 to 1932, archaeology in Iraq was dominated by British teams- including the British Museum working with the University of Pennsylvania at Ur, the fabled home not only of Sumerian kings but of the Biblical Abraham-and regulated by British authorities. The Oxford- educated, English woman Gertrude Bell, who had worked for British Intelligence in the Arab Bureau in Cairo, was appointed honorary Director of Antiquities in Iraq by the British-installed King Faysal in 1922. A most able administrator, having served as the Oriental secretary to the High Commission in Iraq after the war, Bell was responsible for approving applications for archaeologists, and thus for determining where in Iraq excavators would work. She was also the major force behind the wording and passage of the 1924 law regulating excavations in Iraq, a result of which was the founding of the Iraq Museum and the legitimatization of partage’. P.55.

‘Archaeologists should question their support of nationalist retentionist cultural property laws, especially those who benefit today from working among the finds in the collections of their host university museums ,collections which could not now be formed, ever since the implementation of foreign cultural property laws/ And they should join museums in pressing for the return of partage, the

principle and practice by which many local and encyclopedic museum collections were built in the past.’ P.154.

See also James Cuno, Whose Culture? The Promise of Museums and the Debate over Antiquities, Princeton University Press, 2009, pp. 38, 63-64,110.

Zahi Hawass, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Zahi_Hawass

K. Opoku, Zahi Hawass Strikes again

https://www.modernghana.com/news/242484/24/zahi-hawass-strikes-again.html

K. Opoku, Hawass Requests Return of Nefertiti, Egyptian Queen Held in Berlin, Germany,

https://www.modernghana.com/news/244699/1/hawass-requests-return-of-nefertiti-egyptian-queen.html

8. A recent report commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron concluded that France responsible for ‘extreme violence’ in the Cameroon independence war. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/le-monde-africa/article/2025/01/28/france- responsible-for-extreme-violence-in-cameroon-independence-war-report- finds_6737523_124.html

9. See the Annex below.

10. K. Opoku, Berlin Plea for the Return of Nigeria’s Cultural Objects: How Often Must Nigeria Ask for the Return of Its Stolen Cultural Objects?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/182279/1/berlin-plea-for-the-return-of- nigerias-cultural-ob.html K. Opoku, Is the Absence of a Formal Demand for Restitution A Ground for Non-Restitution?

https://www.modernghana.com/news/162530/is-the-absence-of-a-formal- demand-for-restitution-a-ground-f.html

It was common to hear Western museums claim that African governments had not claimed the return of their looted artefacts. The British Museum favoured this line of defence to mean that the owners themselves have shown no interest in the restitution of their artefacts and so there was nothing for them to do. But is it not the duty of one who receives obviously stolen goods to inform the owner? Most Africans did not know until recently, where their treasures wrenched with violence were kept in Western countries that impose difficult visa requirements on Africans who seek to visit. For instance, a Ghanaian who wants to visit Europe may have to travel to Abuja, Nigeria, where the European country has an embassy or consulate.

The denial that there has been a request for restitution of looted artefacts always took grotesque proportions. The late Oba of Benin, Erediauwa sent his brother, Prince Edun Akenzua, in March 2000 to make a request for the restitution of the Benin artefacts which was deposited with British Parliament under the title of ‘The Case of Benin’ Memorandum submitted by Prince Edun Akenzua to the Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport, Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix 21, House of Commons, The United Kingdom Parliament, March 2000

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199900/cmselect/cmcumeds/371/371ap 27.htm

The Case for Benin is in the official records of the British Parliament, Hansard and became known as Appendix21. Years later, many were still claiming there had been no request for restitution by Benin. The British Museum played this game and obliged the Nigerian Government to write again in 2021 another formal request to the British Museum for the Benin artefacts. The British Museum has so far not responded to that request and not returned any Benin artefacts. So much for the respect of the Benin people, the Nigerian Government, and the African peoples.

The British Museum continues offering vague answers to the restitution demand:

‘The Museum remains actively engaged with Nigerian institutions concerning the Benin Bronzes, including pursuing, and supporting new initiatives developed in collaboration with Nigerian partners and colleagues.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested- objects-collection/benin-bronzes

ANNEX

Letter from the Nigerian Commission on Museums and Monuments ((NCMM) to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, requesting the return of Looted Benin artefacts given by Robet Owen Lehmann to the Museum of Fine arts, in 2012.

STATEMENT OF THE NATIONAL COMMISSION ON MONUMENTS AND MUSEUMS CONTROVERSIAL DONATION OF LOOTED BENIN ART

We have read with trepidation the donation of thirty-two works of Benin Art precisely 28 Bronze and six Ivories looted during the Benin Massacre of 1897 by one of the heirs of the beneficiary of the expedition Mr. Robert Owen Lehman to the Museum of Fine Art

Boston U.S.A.

The collections which form part of the exploits of the British Expedition were taken out illegally on the pretext of spoils of war.

Without mincing words, these artworks are heirloom of the great people of the Benin Kingdom and Nigeria generally. They form part of the history of the people. The gap created by this senseless exploitation is causing our people, untold anguish, discomfort and disillusionment.

It is very saddening that the Museum of Fine Arts Boston U.S.A. who now claim to be the new beneficiary of these works indicate that the donation met all legal standards. One wonders what they mean by this. Are they working out of the UNESCO Conventions and other standard setting instruments?

We are vehemently opposed to this stance by the management of the Museum of Fine Art. Objects taken illegally should be returned to their rightful owners and in this case the people of Nigeria. No one can give objective and true history of their patrimony however much they tried than the true owners.

If these art works adjudged to be great, are so wonderful to move into the public domain of the United State, would it not be more appropriate if they are first returned to their home where they will be meaningful and happy to thrive helping to define reality for the people, explaining the past and shaping the future.

For the avoidance of doubt, we hereby place it on record that we demand, as we have always done, the return of these looted works and all stolen, removed or looted artefacts from Nigeria under whatever guise.

We wish to also call on the management of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, US to as a matter of self-respect return the 32 works to Nigeria, the rightful owners forthwith.

Yusuf Abdallah Usman Director General National Commission for Museums and Monuments Abuja.

IMAGES

Members of the notorious British Punitive Exhibition of 1897 posing proudly with looted Benin ivories and bronze objects.

BENIN TREASURES RETURNING TO LEHMAN

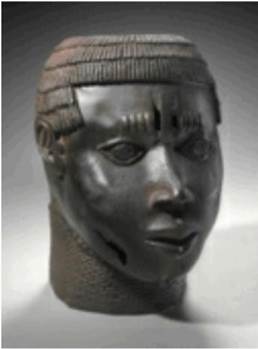

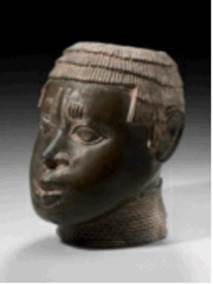

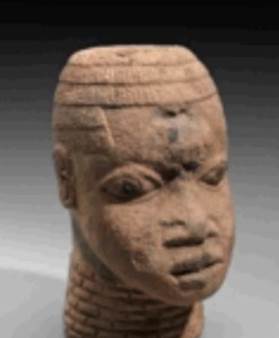

Commemorative head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria.

Mounted ruler, so-called Horseman, Benin, Nigeria.

Relief plaque depicting a dignitary with drum and two attendants striking gongs, Benin, Nigeria.

Relief plaque depicting a battle scene, Benin, Nigeria.

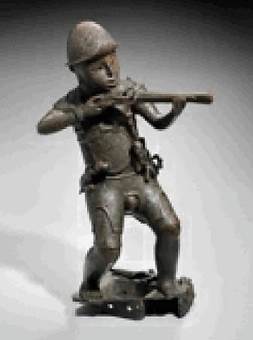

Portuguese soldier with a gun, Benin, Nigeria.

Relief plaque showing a dignitary with a drum and two attendants striking a gong, Benin, Nigeria.

Pendant showing the Oba and two dignitaries, Benin, Nigeria.

Pendant showing a Queen Mother playing a gong, Benin, Nigeria.

Staff showing a bird of prophecy, Benin, Nigeria.

Commemorative head of an Oba, Benin, Nigeria.

Relief plaque depicting a battle scene, Benin, Nigeria.

BENIN TREASURES THAT MFA CONSIDERS IT OWNS LEGITIMATELY AND WILL REMAIN AT MFA

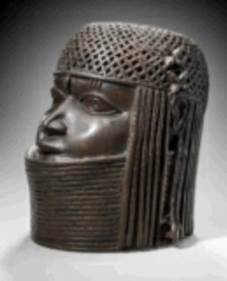

Commemorative head, Benin, Nigeria.

Commemorative head, Benin, Nigeria.

Pendant showing an Oba and two dignitaries, Benin, Nigeria.

Relief plaque showing two officials with raised swords, Benin, Nigeria.

Relief plaque depicting a war chief with two attendants, Benin, Nigeria.