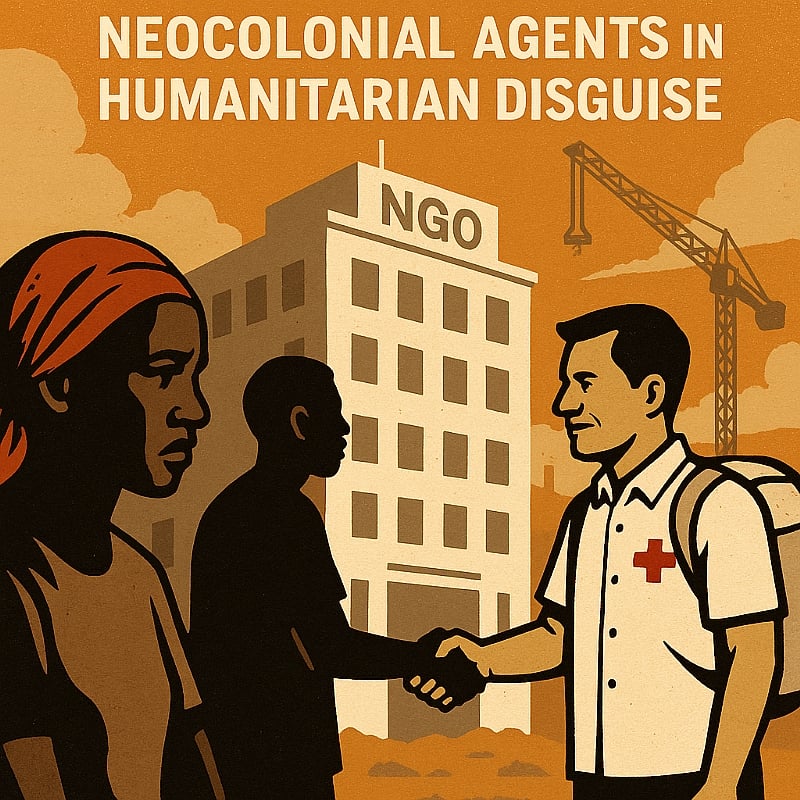

In the shadowy corridors of global development and humanitarian aid, a complex web of influence has quietly emerged . At first glance, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) appear to embody compassion, altruism, and justice. Their logos, catchy slogans, and emotive campaigns paint a picture of hope and empowerment for struggling communities. But a deeper look into the structure, operations, and interests of many of these organizations reveals a troubling truth: behind the smiling faces and free aid, a new form of neocolonialism is taking root one disguised in benevolence but driven by power, control, and exploitation.

The term “NGO Industrial Complex” refers to the institutional entanglement of development agencies, international NGOs, donor governments, multinational corporations, and financial institutions, all of whom operate under the guise of aid but often perpetuate cycles of dependency and underdevelopment. While some NGOs do offer genuine assistance, many others function as soft-power instruments of Western geopolitical and economic interests.

Historically, colonial powers subjugated territories through force. Today, the tools have changed funding, policy consultancy, and technical support are now the weapons of choice. The objectives, however, remain strikingly similar: control resources, dictate policies, and maintain the ideological dominance of the Global North over the Global South. Through NGOs, foreign interests gain unprecedented access to domestic affairs, often bypassing national sovereignty under the banner of “partnership” or “capacity-building.”

One glaring manifestation of this neocolonialism is how international NGOs routinely set development agendas for African nations, frequently without local consultation or cultural context. These organizations arrive with pre-packaged solutions, tailored to donor expectations rather than indigenous realities. Consequently, local voices are silenced, traditional knowledge systems dismissed, and grassroots innovations overlooked. The result is a development model that alienates communities from their own progress.

Furthermore, the NGO sector has become a lucrative industry in itself. High-paying expatriate staff, bloated administrative costs, and donor-driven targets have turned many NGOs into bureaucratic machines more focused on survival and image than on transformation. Billions of dollars are funneled through these organizations annually, yet poverty, disease, and inequality persist and in some cases, worsen. One must ask: if aid truly worked, why has it become a permanent feature rather than a temporary bridge to self-sufficiency?

In post-conflict regions like South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and parts of the Sahel, NGOs operate with an alarming level of impunity, often replacing state functions and eroding government accountability. Instead of strengthening state institutions, they become parallel structures, distorting local economies, and cultivating a dependency syndrome. Local NGOs, rather than being empowered, are frequently relegated to subcontractors for larger international entities, perpetuating power imbalances and stifling African agency.

This is not a call to reject all forms of international assistance, but rather a call for radical reimagination. Africa needs solidarity, not saviorism. We need partnerships rooted in mutual respect, not paternalism. Development should be driven by local priorities, not donor interests. And most importantly, Africans must reclaim the narrative of their own liberation and progress.

The time has come for a decolonization of aid. Governments, intellectuals, and civil society actors across the continent must critically interrogate the roles and impacts of NGOs. Rather than being dazzled by donor money and foreign accents, we must prioritize self-reliance, local expertise, and home-grown solutions. Pan-African cooperation, investment in indigenous knowledge systems, and the empowerment of community-based organizations offer a more sustainable and dignified path forward.

In truth, the most dangerous form of control is not the one imposed by force, but the one disguised as help. unless checked, will continue to undermine Africa’s sovereignty, dignity, and potential. To break free, we must recognize that the fight for true independence did not end with the lowering of colonial flags, it continues today, in boardrooms, funding cycles, and development frameworks. And it is a fight we must win.