I read with deep concern the recent statements made by Dr. Mohammed Jibril, a lecturer at the University of Ghana, suggesting that “students nowadays do not learn” and calling for the reintroduction of university entrance exams. While discussions around improving academic standards are welcome, the manner and tone in which these remarks were delivered are not only unfortunate but deeply disappointing to the thousands of students who strive daily to uphold the values and excellence associated with this prestigious institution, I feel intellectually compelled and morally obligated to respond.

Let me begin by acknowledging the legitimate concerns that many educationists have raised regarding falling academic standards and the need for more rigorous quality control in Ghana’s tertiary education system. Indeed, such conversations are necessary, and scholars are well within their rights to propose solutions such as entrance exams, aptitude assessments, or stricter academic regulations.

However, where Dr. Jibril’s intervention falters is in the language and tone he employed. To dismiss an entire generation of university students as not learning is not only empirically unfounded, but it is also rhetorically damaging. This is not constructive criticism, it is a sweeping generalization that fails the basic test of academic nuance and intellectual fairness.

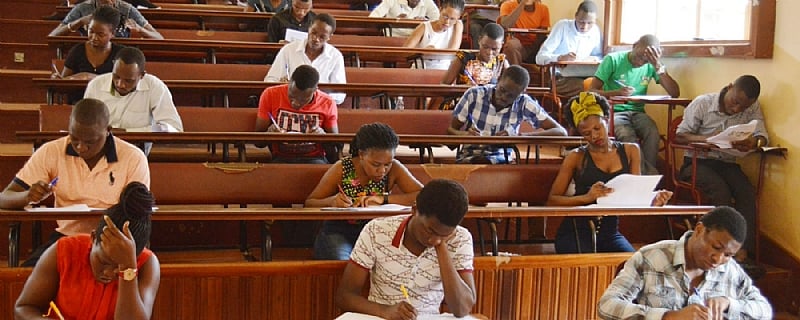

In a time where students are battling economic hardship, limited resources, mental health challenges, and a rapidly changing world, it is irresponsible to trivialize our struggles and efforts. Many students juggle full academic loads with part-time jobs, entrepreneurship, family responsibilities, and even advocacy. Yet, despite these challenges, they rise daily to meet their academic obligations with resolve and tenacity.

One needs only to look around contemporary Ghanaian society to see the fruits of the very education system Dr. Mohammed Jibril now undermines. Individuals like Senyo Hosi, Yaw Ampofo Ankrah, Elsie Effah Kaufmann, and many young innovators, lawyers, doctors, and civil servants are all products of this generation. Are they also part of the “students who do not learn”? The success stories emerging from institutions like the University of Ghana tell a different, more accurate story one of perseverance, excellence, and progress.We are not asking for praise, but for fairness. We do not demand flattery, but accuracy.

It is disappointing if not ironic that such commentary should come from a senior member of academia whom i so much respect, your words carry weight not only within lecture halls but across public discourse. The role of a lecturer extends beyond the delivery of lectures, it encompasses mentorship, motivation, and advocacy for student welfare and academic growth. When those entrusted with this responsibility resort to public criticism that paints all students with a single brush, it reflects more a failure in empathy than in pedagogy. It is therefore expected that such power will be exercised with balance, evidence, and dignity.

To be clear advocating for reforms in higher education it would be in Dr. Mohammed Jibril’s own academic and professional interest to offer a written clarification not only to affirm the authenticity of your views, but also to dispel growing speculation, among students across the globe and observers alike, that the statement was crafted to serve an agenda beyond academic reform. I personally doubt such claims, but your silence risks allowing misinformation to grow unchecked.