Cover design by Obedirwoth

Cover design by ObedirwothThe following is a sample chapter from my novel The United States of Africa.

“I propose to show how in practice African Unity, which in itself can only be established by the defeat of neocolonialism, could immensely raise African living standards.” — Kwame Nkrumah.

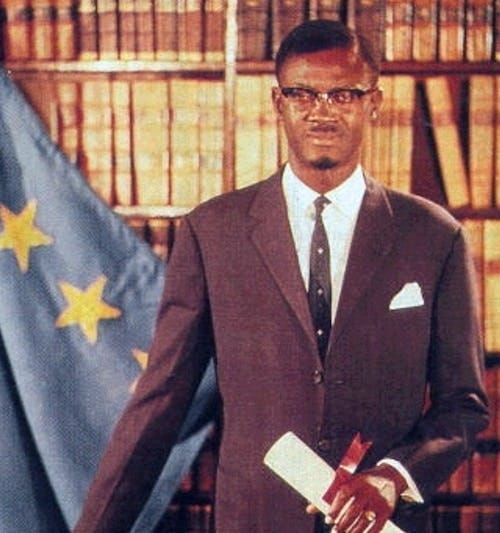

Not since the 1961 murder of Patrice Lumumba had there ever been this level of global protests for an African leader as the ones that erupted after an American general seemed to threaten Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traore in April, 2025.

In 1961, when word got out that Lumumba was killed by Belgian and Congolese assassins, students took to the streets in New York, London, Paris, Cairo, and other major cities. The previous year, the U.S. and Belgium, Congo’s former colonial exploiter, who didn’t want to yield control of the copper revenue, engineered a military coup by Colonel Joseph Desire Mobutu, later known simply as Mobutu. Few Congolese knew Mobutu was recruited by the CIA in 1959 while studying journalism in Belgium.

Patrice Lumumba. Wikimedia Commons photo.

Lumumba and two close political comrades, Joseph Okito and Maurice Mpolo, were killed by firing squad on January 17, 1961. Their bodies were chopped up like steak and burned. Their bones were crushed into powder and then dissolved in sulfuric acid by Belgian agents. The killers plucked out two of Lumumba’s teeth and took them to Belgium as souvenirs. Yet these Belgians were the ones who accused the Congolese of being “savages.” One tooth was returned to Congo for proper burial in June 2022. The other was lost.

The Belgians returned Lumumba’s tooth, his only remains, in 2022.

In Harlem, Malcolm X organized protests denouncing Lumumba’s murder. The poet and activist, Maya Angelou, was one of several Pan-Africans to storm the floors of the United Nations Security Council, disrupting a meeting. They were wrestled and thrown out by security guards. Friends at the Cuban diplomatic mission helped them gain access into the UN building.

Sixty-four years later, supporters of Africa around the world weren’t taking chances. Word got out that in early April, General Michael Langley told the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee that Burkina Faso’s Capt. Traore was spending his country’s gold export revenue “on his government,” and that this somehow harmed US interests. Langley was the Black commander of the US Africa Command, also known as AFRICOM. Remarkably, the general had never complained while Burkina Faso was dominated and exploited by former colonial power France, who benefitted from the mineral resources of all its former African colonies.

Africa watchers had seen this game before. First came the critical statements by U.S. officials about human rights abuses and corruption. These statements are then amplified by the usual suspect corporate media outlets. They then take a life of their own. Suddenly, Americans who wouldn’t even know where to locate a particular African country on a map, were convinced that its leader presented a security threat to the United States and needed to be taken out. Such was the propaganda that preceded the NATO invasion of Libya.

Qaddafi was first demonized for several months before NATO bombs started raining on Libya in 2011. Even the suspect journalists got involved in the lynch-mob. In early 2011, a BBC reporter asked John McCain in an interview, “Senator when are we going in?” By the end of October, Qaddafi was dead. A bayonet was stuck up his rectum then he was shot several times. Libya, once Africa’s most prosperous country, was plunged back into the stone age. So much for the Western civilizing mission in Africa.

So Africans weren’t taking chances with Traore. General Langley’s comments went viral. He was denounced as an “Uncle Tom” selling out an African leader. There were street protests in support of Burkina Faso and Traore, in New York, London, Paris, and throughout Africa, the Caribbean and South Africa. “Hands off Traore,” “Sankara Lives,” “Ready to die for Traore,” and “African Unity Now,” the signs read. Marches were held from Johannesburg to Cairo, from Accra to Los Angeles, and from London to Port of Spain, Trinidad, where a secondary school student kept chanting, “Where ma AK 47 and ticket to Ouagadougou!”

Pan-Africans believed Traore was being targeted because of the seismic political transformations in three West African countries, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger.

In Mali, after Asimi Goita seized power in 2021, he expelled the French military and ambassador out of the country. This was unheard of. An African leader expelling a European? Goita asked: If France’s military was so powerful, why had it not succeeded in helping Mali to halt the radical Islamist forces who’d seized a huge chunk of the country? Goita posed another question: Might France be collaborating with the fighters in order to justify the need for its military presence in Mali where they also dominated the economy?

When Traore came to power in Burkina Faso in 2022, he adopted the same attitude toward France, kicking out its military. Traore also seized control of the country’s mineral and natural resources and forced foreign mining companies to renegotiate contracts and offer better terms for Burkina Faso. This was what Lumumba tried to do in 1960 with the Belgians and instead he ended up dead. Traore was continuing the journey of self-sufficiency that Thomas Sankara started before he too was murdered in 1987. Sankara’s mantra was: “We must produce what we consume, and consume what we produce.”

The third military take-over, in pattern with Goita’s and Traore’s, was on July 26, 2023 when General Abdourahmane Tchiani deposed President Mohammed Bazoum in uranium-rich Niger. That was the last straw. France had had enough of Africans presuming to speak for themselves. The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), issued a strong condemnation statement and vowed military intervention unless Bazoum was restored to power within two weeks. But there was a thick French accent in the air.

These types of threats and gunboat diplomacy might have worked in the 1960s. Africa was changing rapidly. Tchiani, Traore, and Goita came together and signed a military cooperation pact. The agreement specified that any attack on either Mali, Burkina Faso, or Niger, would be regarded as an attack on all three countries. They vowed to fight any war of aggression collectively. Almost two years later, Tchiani was still in power and no such attack had occurred. This didn’t mean the three countries wouldn’t be invaded in the future so in order to fortify their defenses the three countries quit ECOWAS and formed the Alliance of Sahelian States, declaring it the nucleus of a future United States of Africa. By working together they had demonstrated that Pan-African unity could stand up to the West.

There would be no repeat of Libya this time.

After first tossing out the French military, Niger turned its eyes on the three American bases in the country, including the $100 million Niger Air Base 201 which was for surveillance drones. The Americans were also asked to pack and leave. Soon, Western mouthpieces like The New York Times started referring to the Alliance of Sahelian States as the “coup belt,” as if the suit-and-ties belt of corrupt African dictators all over the continent were delivering anything but misery for their citizens. On the other hand, Africans who had seen any past resistance to Western imperialism crushed, realized they were living in a pivotal moment in history. Three African leaders had stood up and defied the West and NATO had not rained bombs on them.

This was the spark needed to rekindle the journey toward a United States of Africa initiated at the 1963 Organization of African Unity (OAU) conference in Addis Ababa by Nkrumah. Would these African leaders squander another golden opportunity? In the euphoria that accompanied decolonization Nkrumah and Guinea’s Sekou Toure and Mali’s Modibo Keita gave regional unity a try in the 1960s. They formed the Union of African States in 1958, but it was dissolved in 1961. Would the leaders of the Alliance of Sahelian States fare better? This time, would the seed planted by the alliance germinate and grow? Would they heed the cry for unity that was demonstrated by the global Pan-African rallies in support of Burkina Faso when faced with American threats?

The leaders of the Alliance of Sahelian States called a conference in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, for uniting Africa, and selected February 16, 2026 as the date. Several African leaders of neocolonial states denounced the invitation. February 16, 2026 was the date for the annual AU conference. Was the Alliance of Sahelian States trying to disrupt and destroy the AU? The AU secretariat wrote a strong letter of protest and rebuke to the foreign ministries of the Alliance countries. Once again, there was a thick French accent in the air. This time the French were taking no chances. The foreign minister flew to no less than 15 African capitals to persuade the leaders not to give any thought to the Ouagadougou summit. Promises of more foreign aid were made.

The Sahelian Times published an editorial under the headline, “Ouagadougou Summit For Unity; Addis Ababa Is For Tea.” The editorial itself was remarkable for its brevity. The entire text read: The AU meeting in Addis Ababa is a tea party. The meeting in Ouagadougou is to sign a union document for the United States of Africa. Long live Kwame Nkrumah! Long live Thomas Sankara! Fatherland or Death, we will win.”

The mini-editorial was quickly seized upon by influencers who produced videos for the Pan-African world that repeated the text while flashing images of Nkrumah, Modibo Keita, and Sekou Toure.

One couldn’t switch on a smartphone without encountering some content urging African leaders to attend the Burkina Faso summit. Journalists, students, union leaders, civic organizations, even some religious leaders, all celebrated the call to action. The main topic of discussion on social media, on television and radio shows, in the newspapers, on the streets, and even in some Parliaments was whether the leader of that particular country would go to Ouagadougou or Addis Ababa. Very soon the question was simplified to: “Unity or tea?” The question was soon emblazoned on millions of T-shirts throughout the continent. A young student at Uganda’s Makerere University even composed a song called Give Me African Unity over Chai, that broke the Internet, gaining 500 million views, chai being the Kiswahili word for tea.

D-Day arrived on February 16, 2026. Ten African leaders showed up at the Ouagadougou summit while 44 attended the Addis Ababa meeting. The Sahelian Times started referring to the Addis Ababa summit as “The Monrovia II Conference.” The reference was to the African countries that doomed the continent’s first attempt at unity during the 1960s. Those countries, including Liberia, whose capital is Monrovia, rejected Nkrumah’s call for the immediate creation of a United States of Africa. They advocated gradual unification, over a period of several years. They became known as the “Monrovia Group.” Those who supported Nkrumah’s call for “unity now” had been referred to as the “Casablanca Group.” No one was surprised when The Sahelian Times started referring to the Burkina Faso gathering as “The Casablanca Conference.” The 10 leaders who attended “Casablanca” signed an interim union document drafted by the foreign ministers of their countries. The leaders who went “Monrovia” made statements and drank tea.

When the 44 African leaders flew out of Addis Ababa back to their respective countries they ran into an unpleasant surprise. One of the presidents was informed by his chief bodyguard that their plane could not land.

“What do you mean we cannot land?” the president asked, glancing out the window. “Military takeover?”

“No excellency,” the bodyguard said. “The people’s take over. No runway is available. There are thousands of students who are lying on the runways, preventing us from landing.”

“What is the meaning of this nonsense? Find out what is going on,” the president said.

The bodyguard returned to the cockpit where the pilots were in touch with ground control.

“Well, what is it?” the president demanded when his bodyguard returned.

“Excellency, they are demanding that you fly to Ouagadougou and sign the unity agreement,” the bodyguard said.

“Who? Who is demanding anything!? I am the president and commander in chief. Who is organizing this coup? Get me the military chief of staff!”

The president rose and accompanied his chief bodyguard to the cockpit.

The pilot handed the president a headset. “This is one of the organizers of the runway protest,” the pilot said.

“Who is this? Listen to me,” the president said. “All of you will face serious consequences. Stop your nonsense and clear the runways or the military will do it.”

“No mister president, you listen to me carefully,” a calm voice said over the headphones. “I am Samaki Mkubwa, a student leader. The army has assured us they will not harm us.

There are hundreds of soldiers dressed in civilian also lying on the runway. Go to Ouagadougou, mister president.”

There was a click and Samaki Mkubwa was gone.

“What is this nonsense!? Get me General Mkali Kweli,” the president demanded.

It took about 15 minutes to get the general on the communication system.

“Excellency…” Gen. Kweli started saying, but the president cut him off.

“No time for Excellency, Excellency. What is going on?” the president demanded.

“Excellency, there are about 20,000 people on the runways and another 20,000 or 30,000 outside the airport. Every airport in the country has been occupied,” Gen. Kweli said.

“Here is what I want you to do,” the president told Gen. Kweli, “I want you to use all necessary force to clear all the runways. I want to land within 30 minutes.”

There was a long pause from the other end.

“Did you hear my instructions general?” the president asked.

“Excellency, I cannot obey those orders. There would be too much bloodshed. Besides…”

“You are hereby relieved of command,” the president said.

The president asked for General Mchokozi Changamira, the deputy chief of staff. When he came on the headphones about 10 minutes later, the president gave him the same order.

Gen. Changamira also refused to obey. After six other senior army officers refused to carry out the order, the president ordered the pilot to try other airports.

The outcome was the same. All the airports were occupied by demonstrators.

“How could something like this have been organized without my knowledge or our intelligence people?” the president asked his chief bodyguard.

“Excellency, with social media, we are dealing with ghosts,” the chief bodyguard said.

When the president called his counterpart in a neighboring country, he discovered that he too was encountering the same predicament. The students had organized a continental-Africa protest in support of “Casablanca.”

Each country had coordination committees with WhatsApp groups. Thousands of universities and secondary schools participated. The turnout was so high in each country that young military officers refused to intervene when ordered by their commanders.

The students had allowed a few airports in each region of the continent to remain open for international flights that were diverted. In addition to the airport protests, students and many of the young officers who joined them took to the streets, wearing T-shirts with the images of Marcus Garvey, Kwame Nkrumah, Thomas Sankara, Patrice Lumumba, Malcolm X, and Ibrahim Traore. The T-shirts were emblazoned with the words: Unity Over Chai! or More Unity Less Talk! or No Monrovia II! or United States of Africa!

Some African presidents flew straight to Ouagadougou to sign the interim unity documents when they could not land. Some landed in the regional airports and took refuge hoping the protests would fizzle. Some flew to Paris and London to consult with their masters.

Then, one by one, the African presidents made their way to Ouagadougou. By July 20th, 2026, 45 presidents had signed the unity document. There were five military takeovers in countries whose leaders were still either in Paris or London awaiting instructions from their real bosses. All of the five new military leaders traveled straight to Burkina Faso and signed the agreement. The remaining leaders did not want to face a similar fate and they too flew to Burkina Faso.

On January 1, 2027, all the African presidents became governors of their respective countries, which became states of the union. These governors then elected one of their own as the first leader of the United States of Africa.

The new leader’s title was Citizen Protector of the United States of Africa.

The first official act of the interim Parliament was to declare that any African descendant in the diaspora had the right to automatic citizenship the minute she or he landed on African soil.

The second official act was to make Kiswahili Africa’s new national language.

Support the kickstarter campaign for The United States of Africa.

Allimadi publishes www.blackstarnews.com and hosts a weekly “Black Star News” show on WBAI 99.5 FM New York radio www.wbai.org every Tuesday at 3PM. He’s also a PhD student in the History Department at Howard University.