Ghana is a nation deeply intertwined with faith. From jubilant church services to fervent personal prayers, Ghanaians often turn to the divine for guidance and blessings. But what happens when those blessings seem to contradict each other? The current situation with the Ghanaian Cedi, under the new government of President John Dramani Mahama, perfectly illustrates this complex dynamic.

For years, the value of the Cedi against the US dollar has been a source of national anxiety. During the previous administration, the Cedi plummeted to alarming lows, hitting around GHS17 to 1 USD at one point. This depreciation crippled businesses, inflated prices, and generally eroded the economic stability of the country.

Now, the tables have turned. Under the new leadership of John Mahama, the Cedi has strengthened considerably, hovering around GHS10 to 1 USD. This appreciation is undoubtedly welcomed by many. Importers, in particular, are breathing a sigh of relief.

A stronger Cedi means lower import costs, potentially leading to reduced prices for consumers and boosted profits for businesses. It’s a prayer answered, a sign of economic improvement, a reason to be optimistic.

However, this “blessing” for some is a source of woe for others. Many Ghanaian families rely heavily on remittances from relatives living and working abroad.

These remittances are often the lifeline that sustains these families, funding education, healthcare, and basic necessities. The strengthening Cedi, while positive for the national economy, directly impacts the value of these remittances, effectively shrinking the amount of Cedi they receive for each dollar sent.

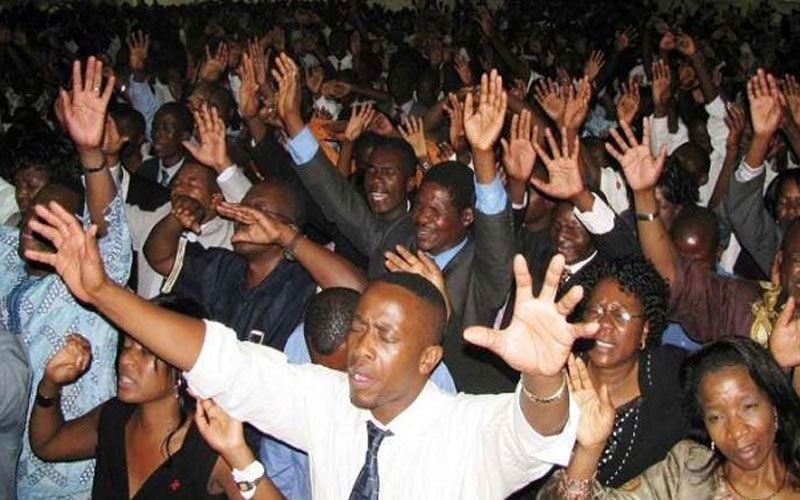

This discrepancy has led to a fascinating and perhaps somewhat ironic situation. And in my mind’s eyes I can see families gathering for all-night prayer meetings, earnestly beseeching God to allow the Cedi to depreciate. The desperate pleas, often articulated in tongues, filled the night air with fervent requests for economic relief: “Hribababa, shakala bababa, Sandala

bababa.”

The stark contrast between the prayers of importers and the prayers of remittance-dependent families highlights the inherent difficulty in satisfying everyone’s needs and desires.

God, it seems, must be very busy indeed. When it rains, farmers rejoice, while those fearing floods pray for it to stop. And when the sun shines brightly, those same farmers may find themselves praying for rain.

This begs the question: can a single economic policy, or even divine intervention, ever truly benefit everyone? Probably not. The reality is that economic forces are complex and intertwined, often creating winners and losers. One group’s gain can, unfortunately, be another’s loss.

Given this reality, it wouldn’t be surprising to see importers organising their own prayer meetings in the coming days, passionately appealing to God to solidify and further enhance the Cedi’s value.

This situation underscores the human tendency to seek divine intervention when faced with economic challenges, and the inherent conflict when different groups have diametrically opposed needs.

Ultimately, the fluctuating Cedi and the contrasting prayers it inspires serve as a potent reminder of the complexities of economic policy and the challenges of governance.

Perhaps, the most effective prayer is for wisdom, for leaders to implement policies that consider the needs of all stakeholders and strive for sustainable economic stability that benefits the nation as a whole, leaving less need for desperate, conflicting pleas to the heavens.

Anthony Obeng Afrane