(A) The Curse of Lumumba: Why Africa’s Visionaries Are Always the First to Fall

Africa remains a paradox—overflowing with wealth yet haunted by poverty, blessed with minds of steel yet burdened by systems of decay. Since the dawn of independence, the continent has watched as its brightest hopes were dimmed—not by natural fate, but by calculated violence and betrayal. Visionary leaders, from Patrice Lumumba to Thomas Sankara, have sought to forge a new path for the continent, only to be consumed by the very forces they sought to dismantle.

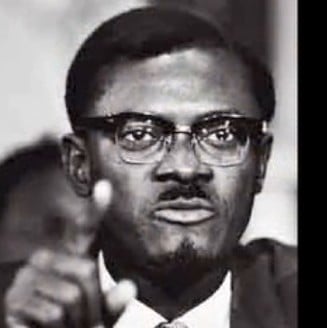

Patrice Lumumba was not a perfect man, but he was a principled one. His dream for a united, self-determined Congo threatened the interests of Western powers and their domestic surrogates. He was captured, tortured, and executed—not for failing his people, but for daring to liberate them on his terms. His body was dissolved in acid, yet his name endures—a ghost reminding Africa of what it might have been. His death did not come by chance. The CIA’s involvement in Lumumba’s assassination highlights the deadly lengths to which imperial forces will go to suppress genuine independence movements in Africa.

Then there was Thomas Sankara, the “African Che.” In just four years, he inspired a cultural and economic renaissance in Burkina Faso. Sankara took bold steps that made the elite uncomfortable: he slashed his salary, denounced foreign aid dependency, empowered women, and launched an ambitious reforestation program to combat desertification. But for all his efforts, he was betrayed and shot dead—by his closest ally, with backing from interests threatened by his independence.

In Nigeria, Murtala Mohammed shook the foundations of the corrupt order during his brief time in power. His tenure was marked by reforms aimed at slashing government spending, reducing corruption, and asserting Nigeria’s sovereignty. Like Lumumba and Sankara, he was cut down at the height of momentum—assassinated in a failed coup, leaving his vision unfinished. His death underscored the point: those who dare challenge the status quo are never given the chance to complete their revolutionary projects.

Even in recent years, the deaths of leaders like Umaru Musa Yar’Adua and John Magufuli have followed a similar pattern. Both sought to prioritize national interest over foreign dictates, both took steps to protect the people from exploitative forces, and both died under questionable circumstances, with their reforms left incomplete. Yar’Adua’s illness and sudden death, surrounded by political intrigue, raised many unanswered questions, while Magufuli’s sudden disappearance and subsequent death were shrouded in mystery, leaving Tanzania to grapple with the unfinished business of his presidency.

Why does Africa consume its prophets?

This question is not new. Walter Rodney, in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, laid bare the machinery that ensures Africa’s dependency. He argued that the institutions created by colonialism were not dismantled after independence; instead, they continued to serve the interests of the same colonial powers under new guises. The result has been the perpetuation of a system that rewards corruption, exploitation, and dependence, and punishes resistance. Leaders like Lumumba, Sankara, and Mohammed threatened this system, and as a result, they were eliminated.

Frantz Fanon, in The Wretched of the Earth, warned that unless post-colonial states fundamentally rejected colonial political and economic structures, they would merely be dressed in the trappings of independence while continuing to serve the interests of the former colonizers. He cautioned that Africa’s true liberation would come not from changing the faces of leadership but from rejecting the very systems of exploitation that had been implanted during colonial rule. Fanon’s words ring true today: many of Africa’s most promising leaders have been demonized, destabilized, or eliminated precisely because they dared to challenge the colonial inheritance of their societies.

Chinua Achebe, in his searing critique of Nigeria’s leadership in The Trouble with Nigeria, observed that the continent’s leadership was mired in failure not just because of individual incompetence, but because of a systemic crisis of governance. Achebe identified a system that rewards compromise over conviction, and mocks those who dare think independently. This system does not tolerate revolutionary leaders—it smothers them. And as Achebe pointed out, it is not a crisis of individuals but of the very system that produces those individuals.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, a fierce critic of cultural imperialism, insisted that African liberation must begin with a mental and linguistic revolution. Until Africans unlearn the logic of the colonizer and reject the cultural dominance of the West, they will continue to fail to nurture the kind of visionary leadership the continent desperately needs. The political landscape of many African nations is shaped by the logic of the colonizer—leaders are often expected to conform to a Western mold of “acceptable” governance. Those who reject this mold, who think outside the Western-defined box, are seen as threats. This is why Africa’s visionaries—those who seek to prioritize the well-being of their people over the interests of foreign powers—are often silenced.

As PLO Lumumba, a contemporary Kenyan scholar, has passionately stated, “When you are a leader in Africa and begin to think too independently, your days are numbered.” This encapsulates the curse of African leadership—the visionaries are not protected, but are instead eliminated by the forces that seek to maintain the existing power structures.

This is the curse: Africa praises its martyrs and persecutes its visionaries.

We have a long history of erecting statues in honor of our fallen heroes. Streets are renamed, speeches are delivered, and holidays are declared. Yet the revolutionary ideas that these leaders championed die with them. What is left in their place is a hollow form of patriotism—one that celebrates the martyrdom of the individual while refusing to confront the systemic issues that led to their deaths.

What, then, is to be done?

We must stop romanticizing our fallen heroes and start protecting the living ones. The death of a visionary is not the end of their work—it is the signal that a deeper problem is at play. We must stop viewing leadership as a solitary struggle and instead focus on building movements that can sustain the ideas and principles that our fallen leaders embodied. It is not enough to erect monuments to Lumumba, Sankara, and others who have fallen. The real challenge is to create systems of governance that can protect and nurture the leaders who come after them.

This requires a fundamental shift in how we view leadership. Visionary leadership cannot thrive in a society where it is constantly under siege. We must build movements that can defend these leaders from the systemic forces that threaten to destroy them. We need to rethink how we educate our people, how we organize politically, and how we mobilize to ensure that our best minds are protected and allowed to flourish.

In this task, we must begin with our schools, our mosques, our churches, and our street corners—places where consciousness can be raised, and where the seeds of a more revolutionary leadership can be sown. We must teach our young people that true leadership is not about seeking power for personal gain, but about building a society where the needs of the many are prioritized over the interests of the few. This is the kind of leadership that Africa needs. It is not enough to simply mourn the loss of visionaries like Lumumba and Sankara—we must fight to ensure that their legacy is carried forward by the next generation of African leaders.

Because until we defend and institutionalize visionary leadership, Africa will remain a continent where the truth dies young and mediocrity reigns.

(B) The Curse of Lumumba: Why Africa’s Visionaries Are Always the First to Fall

Africa is a continent of paradoxes. Its land is overflowing with natural wealth, from diamonds to oil, to fertile soil that could feed the entire world. Yet, it remains plagued by pervasive poverty, underdevelopment, and stagnation. Its people have minds as sharp as steel, yet they are often bound by systems of decay—both inherited and constructed. Since the dawn of independence, the continent has repeatedly watched as its brightest hopes and most principled leaders were extinguished. Not by the unyielding forces of nature, but by calculated violence and betrayal—usually from those who stand to lose from a shift in the power dynamics.

Patrice Lumumba: A Martyr for Congo’s Freedom

Patrice Lumumba was not a perfect man, but he was a principled one. His dream for a united, self-determined Congo threatened the imperialist interests of Western powers and their domestic surrogates. In his short time in power, Lumumba had already shown the determination to act on his principles, resisting foreign interference in the country’s affairs. This audacity led to his capture, torture, and brutal execution—by both Belgian and CIA-backed forces. His body was dissolved in acid to erase any trace of his existence. But despite the physical erasure, his name endures, a ghost that continues to haunt Africa—a reminder of the grand dream of independence and unity that Africa could have had, had it not been for betrayal at home and abroad.

The Tragedy of Sankara: The “African Che”

Thomas Sankara, the former president of Burkina Faso, embodied the same spirit of defiance as Lumumba, and his fate was similarly tragic. Often called the “African Che,” Sankara believed that real liberation for Africa could only come from within, through radical self-reliance. Within four years, he brought about a cultural and economic rebirth in Burkina Faso, earning the respect of millions across the continent. His policies included slashing his own salary, promoting women’s rights, banning female genital mutilation, fighting corruption, and planting millions of trees to combat desertification. His administration also dramatically reduced foreign aid dependency, making enemies not only among the global powers but also among the entrenched elite within Africa. Sankara’s idealism and commitment to the African cause cost him his life in 1987, when he was betrayed by his close ally, Blaise Compaoré, who seized power with the backing of foreign interests threatened by Sankara’s independence.

Murtala Mohammed: Nigeria’s Shining Hope Cut Short

In Nigeria, General Murtala Mohammed’s reign as head of state in the mid-1970s represents another example of an African leader with transformative potential tragically cut short. Mohammed initiated radical reforms, slashing government spending, and attempted to reduce Nigeria’s dependency on foreign powers. He stood up to imperialism, introducing measures that promised to create a more just and equitable society. His reforms were a direct challenge to the political elites, many of whom had benefited from corrupt practices. In 1976, only two years into his tenure, Mohammed was assassinated during a failed coup attempt. His death symbolized the dangers faced by African leaders willing to challenge the status quo.

The Modern Pattern: Umaru Musa Yar’Adua and John Magufuli

More recently, we see echoes of this tragic pattern in the leadership of Umaru Musa Yar’Adua of Nigeria and John Magufuli of Tanzania. Both leaders sought to prioritize national interests over foreign influence, to build a more transparent and just society. Yar’Adua’s administration was dedicated to improving the rule of law, addressing corruption, and enhancing Nigeria’s relationship with its neighbors. However, his tenure was cut short by his mysterious death in 2010, leaving his reforms incomplete and his political enemies emboldened.

Similarly, Magufuli, known for his no-nonsense approach to corruption and his focus on infrastructure, was also a thorn in the side of the political establishment. He sought to build a self-sufficient Tanzania, minimizing foreign aid dependence and advocating for policies that would benefit ordinary Tanzanians. Tragically, his untimely death in 2021 left his reform agenda unfinished and his supporters devastated. These leaders, who sought to chart an independent path for their countries, became casualties of the political and economic systems that continue to prioritize the interests of foreign powers over the well-being of the African people.

The Inherited System of Dependency: A Legacy of Colonialism

In How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, Walter Rodney laid bare the mechanisms that continue to stifle Africa’s development. He argued that Africa’s underdevelopment is not accidental, but rather the result of a systematic exploitation designed to keep the continent subjugated. Even after the colonial flags came down, the same structures that facilitated Africa’s exploitation during the colonial era remained intact. These systems continue to serve the interests of global powers, ensuring that Africa remains dependent on foreign aid, foreign markets, and foreign policies.

Frantz Fanon’s work The Wretched of the Earth is particularly relevant here. Fanon warned that post-colonial African states would struggle to achieve true independence unless they radically rejected colonial political and economic structures. Without dismantling these systems, Fanon argued, newly independent African states would merely replace one set of rulers with another, often adopting the same exploitative tactics of their colonizers. This is exactly the scenario that has played out time and again, as visionaries who seek to break away from this legacy are often silenced, removed, or simply eliminated.

Chinua Achebe, in The Trouble with Nigeria, framed the crisis of African leadership as a result of failed systems. Achebe argued that the continent’s challenges were not due to the absence of capable individuals but rather a political system that rewarded compromise over conviction. Leaders who dared to deviate from the norm were marginalized, mocked, or worse, murdered. Achebe’s insight into Nigeria’s political crisis can be expanded to encompass Africa at large, where the political system rewards conformity and punishes integrity.

The Need for a Cultural Revolution: The Path Forward

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s call for a cultural and linguistic revolution is essential to understanding how Africa can break free from the mental chains of colonialism. Wa Thiong’o insists that true liberation must begin with a rejection of the colonial mindset and a reinvestment in indigenous languages, cultures, and forms of governance. Until Africans begin to decolonize their minds and embrace leadership that is rooted in their own traditions and experiences, they will continue to reject their best sons and daughters who do not fit the colonial mold.

The Challenges of Modern Leadership in Africa

In the modern age, the challenges to visionary leadership are more insidious but no less dangerous. Global financial systems, multinational corporations, and international organizations often work in tandem with corrupt local elites to undermine any attempts at self-reliance. Leaders who propose policies that challenge these interests are frequently labeled as tyrants, their efforts branded as threats to stability. This narrative, pushed by Western media and political organizations, often serves to justify the removal of such leaders, either through coups, assassination, or political sabotage.

Building Movements, Not Monuments

To end this cycle, Africa must stop romanticizing its martyrs and start protecting its living visionaries. Monuments and statues of fallen heroes are not enough; they must be supported in life. Movements need to be built that will not only defend these leaders but will also institutionalize visionary leadership. A truly revolutionary vision for Africa must be protected by institutions that promote transparency, accountability, and justice.

Moreover, Africa needs to undergo a renaissance—a return to its roots. Pan-African unity must be prioritized, as Africa’s strength lies in its collective power. Nationalist movements often lead to further division, but a united Africa could stand tall against the forces of imperialism and neoliberalism. The first step is education—both civic and political education that empowers Africans to understand the importance of visionary leadership and how to protect it.

Conclusion: The Curse of Lumumba

The curse of Lumumba is not some mystical affliction. It is a tragedy that reflects the systemic and deliberate suppression of transformative leadership in Africa. The continent must begin to defend its leaders—those who dare to think independently, who center the needs of the poor, who reject foreign control, and who speak truth to power. Only when Africa protects its visionaries in life, not just in death, can it hope to realize the dreams that were once whispered by its greatest leaders.